So François Hollande’s challenge has finally been met: unemployment at the end of his presidential term has fallen and is now lower than when he became president. This was a daunting task, but he reached his aim as the jobless total rose from 9.7% in the second quarter of 2012 to 10.5% in Spring 2015 before eventually falling to 9.6% over the first three months of 2017.

We have definitely seen a shift in the unemployment curve.

However, unemployment still has the potential to fall much lower as it stood at only 7.2% in the first quarter of 2008, so we cannot settle for such high joblessness, which is why fresh steps must be taken to make the job market more adaptable.

The aim here must be twofold: improve the French economy’s ability to create jobs when business is more buoyant, while also seeking to close the skills gap between available jobs and employees’/the jobless’ ability to meet them. It is vital for job growth to be able to flourish in the economy’s healthier sectors and for the French economy as a whole to be able to adjust more quickly to the overall economic cycle through employment and the capacity to garner the necessary human resources to drive buoyant sectors. However, this means cutting back jobs in declining sectors, as the country’s inability to cut jobs creates severe inertia and leaves it ill-equipped to reap the benefits of economic improvement. Sectors that do well after a recession are rarely those that drove the cycle before the dip, so it is important to be able to reallocate resources swiftly to reap the benefits of economic growth when it takes off. These factors are pro-cyclical in nature and can extend and reinforce growth momentum.

Two metrics clearly reflect these notions of the labor market’s reaction time.

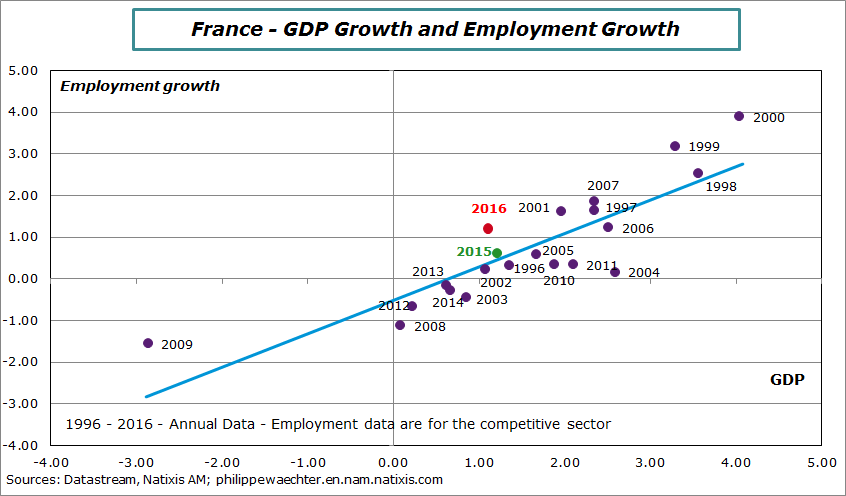

The first is the relationship between economic growth and job growth, and the chart below provides annual data on this between 1996 and 2016.

The blue line shows the linear relationship between the two indicators, and its positive slant suggests that higher growth and faster employment growth go hand-in-hand, with employment rising more quickly when growth is more robust.

However, we can see that the labor market is fairly responsive and growth of 1.2% in 2016 went alongside an increase of 1.2% in employment. An idea can be to endeavor to alter the shape of the blue line in order to promote an acceleration in employment, particularly during periods of recovery. This can also involve an upward shift of the blue curve as a whole to further bolster job growth.

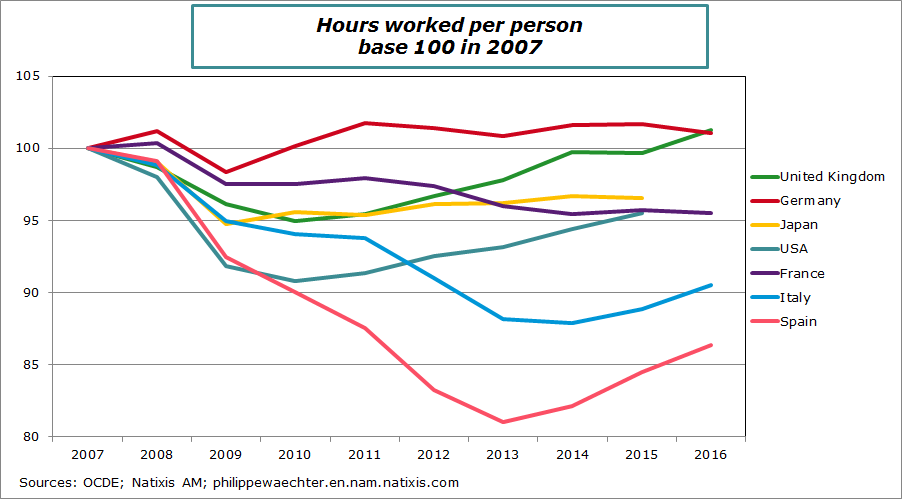

The number of hours worked relative to the population has picked up across all western countries… with the sole exception of France. Meanwhile, in the UK, the surge in working hours has proved to be the primary source of growth as productivity is even lower in that market than elsewhere. This situation in France cannot be attributed to the country’s 35-hour working week, as the indicator we use here reflects the labor market’s ability to adjust to upturns in the cycle, while the 35-hour week is an institutional measure: changing working hours, as François Fillon’s presidential campaign program advocated, would not make the labor market more adaptable and would therefore not have any impact on this indicator.

So the challenge now is the labor market’s ability to adapt to cycle changes and any future shift must be based on achieving this adaptability. This means giving companies the wherewithal to quickly increase or reduce jobs depending on the business cycle. A shift towards Europe-wide standards would make sense here, as today’s companies take very different shapes and forms. The increasing individualization that we are witnessing for employees also applies to companies. It is important to cut back uncertainty for companies in today’s ever more complex world.

However, there must also be a trade-off for employees, and the labor market cannot just be one-sided. In the US and UK, this adjustment involves the ability to generate jobs that are sometimes very badly paid. The British zero-hour contract is not the right answer in my opinion: this flexibility admittedly creates jobs but it does not fit with the French tradition. Companies’ ability to swiftly lay off staff creates uncertainty for workers, and the unemployed often remain stuck in their joblessness for a long time, particularly when they are short of qualifications. This is exactly where the El Khomri labor law lacked balance as it did not reduce uncertainty for workers.

The best way to cut back uncertainty is for the employee to know his or her value, but this is heavily dependent on the training he/she has received and the qualifications achieved. So it is key for employees, whether in a job or currently unemployed, to be able to stay employable and even improve their employability. Companies must be able to recruit qualified staff to adapt to production processes and meet the specific business sector’s requirements. Either we break down employment and offer small parts of badly paid but plentiful jobs, as is the case in the UK and sometimes Germany, or we try to offer more comprehensive jobs that require higher qualifications, because employees have the credentials needed to carry them out. Herein lies the demanding path that France must follow – as it is the only one that suits the French social model.

The drawback is that these adjustments do not all take place at the same pace. It is very easy to tell companies that they can adjust jobs or that they can change the rules, but it takes much longer for employees to obtain their qualifications.

So the government’s task will be to reduce this imbalance. There has been a tendency in the past in some quarters to create small or part-time jobs to avoid having to address this imbalance, but today a political opportunity is emerging to change French labor market momentum…it should be taken.

This is my weekly contribution to Forbes in France – You can read the published version here (in French)

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog