The Fed’s meeting today is an opportunity to show the dramatic monetary policy divergence between the US central bank and the ECB and the risk for a stronger greenback.

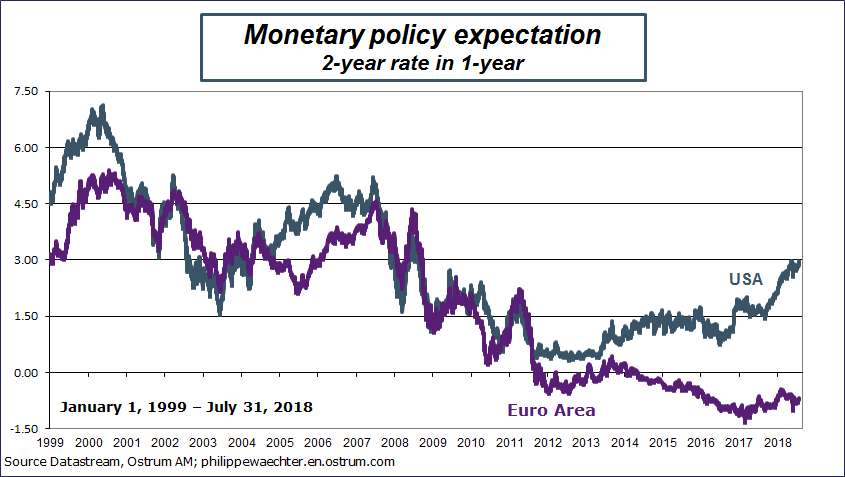

The first graph shows the gap between monetary policies’ expectations in the two countries. The measure here is the 2 year rate in 1 year. The time scale begins with the Euro Area inception in 1999.

The divergence between the two central banks’ strategy has never been so important. It’s a strong support for the US dollar which will continue to appreciate and it’s a source of risks for emerging countries. The strong probability of a US tighter monetary policy in a foreseeable future will support capital outflows reducing liquidity on these markets.

Since 2014, the ECB strategy is very accommodative with zero interest rate and QE since the beginning of 2015. The Euro area was in recession during 6 quarters until the end of 2012 and the recovery was not so strong. This has conditioned the ECB very loose monetary policy.

In addition to these instruments and to change investors expectations, the ECB had and still has a strong accommodative bias in its forward guidance. This can be seen in the negative expected rate in the graph. Recent announcements by Mario Draghi on the end of the QE and higher rates after summer 2019 have not changed investors’ perception on the future of the EA monetary policy. They think that there will be a permanent downside bias on the ECB strategy.

The situation is different in the US. First because the business cycle has been stronger than in the Euro Area. It has started earlier (Q2 2009 vs Q1 2013 in the EA) and in 2014 the unemployment rate was converging rapidly to full employment. There was no anomaly yet between the unemployment rate and the wage rate change. It was still expected that lower unemployment would push wages higher. Such a dynamics was consistent with higher rates.

The situation has dramatically changed with Trump’s election. The recent lowest point was at the beginning of September 2017. Since then, the US rate is trending upward. This reflects the change in the US policy mix which becomes too strong in a full employment economy.

The strong fiscal policy boosts domestic demand while the economy is already at full employment. The tighter monetary policy is just a way to constraint domestic demand and to avoid large imbalances and a higher inflation rate.

A textbook consequence of the strong fiscal policy, due to lower taxes, is higher interest rates, a higher inflation rate, a higher dollar and a larger external deficit. The current upward trend on the Fed’s rate is just the result of the White House fiscal policy. It is not the consequence of a kind of conspiracy against the US economy as it has been said in Washington.

Therefore, as Europe doesn’t want to use the fiscal instrument to boost its growth momentum, the divergence seen on the graph will continue and will increase. Higher Fed’s rate is a necessity to avoid large imbalances in the US. We expect at least four hikes this year and three next year. The consequence will be the flattening of the yield curve and a higher risk of recession in 2020. (see here and here)

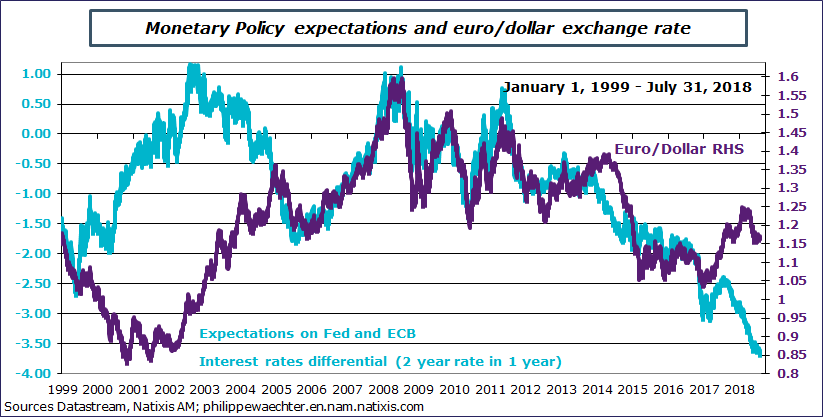

The first consequence of this divergence is that we expect a stronger dollar in a foreseeable future. The graph below shows the on one side the spread between the two rates of the first graph and the exchange rate parity between the US dollar and the Euro. Since the second half of 2004, the correlation between the two indicators has been strong. The current episode suggests that the greenback should be stronger in coming months for two reasons: the first is that there is currently a strong gap between the rates and the exchange rate. The second consequence is that the divergence in rates will continue as the Fed will maintain its tighter bias in the conduct of its monetary policy.

The US dollar/ Euro exchange rate could go below 1.1 or even below.

The argument saying that the external imbalance is a constraint that will not allow a stronger dollar is a non sense for two reasons.

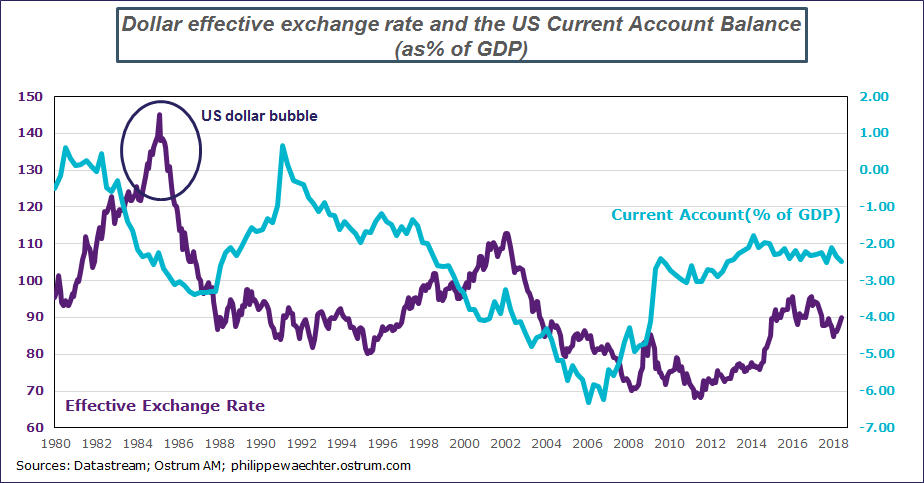

First because the correlation between the dollar and the current account is low as the graph, since 1980, shows. Sometimes the larger current account deficit is consistent with a stronger dollar, sometimes with a weaker dollar. The US has the advantage of being the international currency and its value is not really dependent on the US external balance

Even if the relationship holds, we see that the current account deficit is quite stable. It will probably be bigger in the future after the fiscal policy stimuli. But the role of the Fed is to limit this risk with a tighter monetary policy. The US central bank strategy must counterbalance the fiscal policy accommodation.

The second remark is that the current dollar appreciation is still limited, the interest rate argument (see for the Euro) should provide a support for a stronger exchange rate. It could go higher.

The risk therefore is again on emerging markets. Higher US short term rates and a stronger dollar will push investors to reduce their carry trade positions on emerging markets. Their situation will continue to deteriorate. Rules of the game have definitely changed for them. (see here and here)

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog