A pdf version of this post is available Ten Years on – my Monday Column

On September 15, 2008, the collapse of Lehman brothers set off a shockwave that rippled out right across the world economy. What can we make of this watershed moment 10 years down the line?

The extent and duration of the shock that hit the world economy are still impressive even 10 years later. Some observers had anticipated the property market’s role in triggering the upheaval, but no-one had envisaged the intensity of the shock or how long it would last.

Between the end of Spring 2007 and Fall 2008, the financial system crumbled astoundingly quickly and astonishingly easily, to an extent that remains unbelievable still to this day. The collapse of Lehman Brothers was the culmination point, coming in the wake of other investment banks’ demise – although these previous casualties had been rescued and taken over by other financial institutions – and its bankruptcy was accepted without taking the full measure of the consequences. It was a step into the unknown, and enough to strike fear into the heart of any economist at the time. Risks quickly emerged as insurer AIG was saved just a few weeks later: Lehman marked the final stage in the breakdown process, as the realization dawned that history was on the brink of a new era.

What happened next?

The world economy ground to a halt almost instantaneously as suspicion and mistrust of the financial system took root, even from within. Financing for world trade dried up and trade flows stopped instantly. Shockwaves rippled right across the entire world economy and activity came to a standstill.

How did the authorities react?

In the White House, Christina Romer, who was the chair of (newly elected) Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers at the time, very quickly grasped the magnitude of the shock and its potential consequences. Her primary concern was to make sure that the economy did not fall into a repeat performance of the 1930s, particularly as the 2008 shock was much more extensive.

The initial shock in October 1929 only affected the equity markets and the real estate market was not yet affected, although it would be later on. In 2008, the drop on the equity markets came hot on the heels of the decline on the US real estate market that had already been under way for several months and the impact on US household wealth was very different: households are much more sensitive to property than to share prices as they hold more property than stocks and shares. The situation was not just restricted to the US, with real estate markets in Spain, the UK and France very quickly taking a downturn.

The idea of coordinated budget stimulus made sense to stop the situation deteriorating. The question that bothered everyone at the time was the extent of the financial crisis and the length of time it lasted and Christina Romer highlighted this point in her first assessments of the crisis. Even today the question is still not yet settled as Paul Krugman’s recent op-ed for the NY Times revisited the arguments he outlined at the time on the failure to adopt the necessary resources to set the economy back on the right track.

Meanwhile, looking to the central banks, the Fed was the first – along with the Bank of Japan – to cut back its leading rate to 0% in December 2008. The other banks also reacted but they took their time and the Bank of England only cut back its bank rate to 0.5% in March while the ECB put down its refinancing rate to 1% in April 2009.

This policy mix very quickly had the desired positive effect as the second quarter of 2009 is usually considered to be the recession’s trough.

And what about the financial sector?

The banking and financial sector was at the very epicenter of the crisis in 2008. We can’t rewrite history, but after Lehman, every bank examined the value of its own securities portfolios and its partners’ and competitors’ holdings. Interbank relationships can only work when banks trust each other, and the system seizes up when they don’t. This mistrust forced central banks to provide massive input and intervene to take the place of market mechanisms so that the various economies could continue operating.

Governments very soon took steps to restrict the risk of the financial crisis spreading out from the banking sector as they aimed to curb the risk of bankruptcy. Every bank in France had quasi-equity, regardless of its situation, with a program that amounted to more than €400bn, while in the US the TARP came to over $700bn. This episode was one of the paradoxes of this period, as every banking client wondered if his/her bank would hold up: if a bank like Lehman could go under, then what would happen to his/her probably smaller and undoubtedly less prestigious bank? Governments tried to avoid bank runs as they sought to convince their populations that the Lehman shock would not spread and that the banking system was solid. Yet, they still implemented massive programs to ward off a crash in the banking sector, so this contradiction in the perception of banking risk played a major role in the way the various participants in the economy acted at the time, with many wondering why all governments were implementing vast programs to stave off potential bankruptcies when there was supposedly no risk for the banking system.

How did things go from a macroeconomic standpoint?

The 2008 crisis was first and foremost a private debt crisis with an accumulation of an asset financed by debt. Public debt was in no way a problem at that point, but the ensuing adjustment process saw a transfer of debt from the private sector to the public sector. A high public deficit helped smooth out macroeconomic shocks over time by sharing out the cost: the role of public debt is to absorb shocks over the long term and avoid any one specific participant in the economy having to carry the entire cost, which would be damaging for that specific player and the economy as a whole. This is why it always seems a bit strange to worry about public debt levels as usually it is simply an exercise in sharing out cost. What we should be thinking about is the nature of the cost rather than the extent of public debt.

So keeping down public debt was a mistake?

It is often a mistake and at the start of the last decade, it clearly was a mistake and explains the recession in the euro area and the ensuing sovereign debt crisis. However, austerity forced the ECB to become the lender of last resort for the euro area and Mario Draghi changed the course of events for the euro area in London on July 26, 2012 with his famous “whatever it takes” comments.

All those involved in the economy were still in shock despite the recovery in 2010 and there was little expansionary policy across the board. Implementation of austerity policies was a mistake as they dented already sluggish demand for companies’ goods and services, with the aim of curbing public expenditure. Companies therefore took a downturn, plunging economies into a long recession that lasted six quarters.

The German approach was to make the budget balance the key to renewed robust growth, but this strategy did not hold water and did not deliver the expected results. This type of strategy put the onus for macroeconomic adjustment on the private sector, which was already weak, depriving the economy of any leeway to share out the impact of shocks: this approach cannot and did not work. It could potentially have been feasible if there had been a federal budget that could make up for local inadequacies, but this was not and is still not the case. And the issue of a federal budget is still a subject for heated debate between France and Germany today, and the matter has in no way been settled.

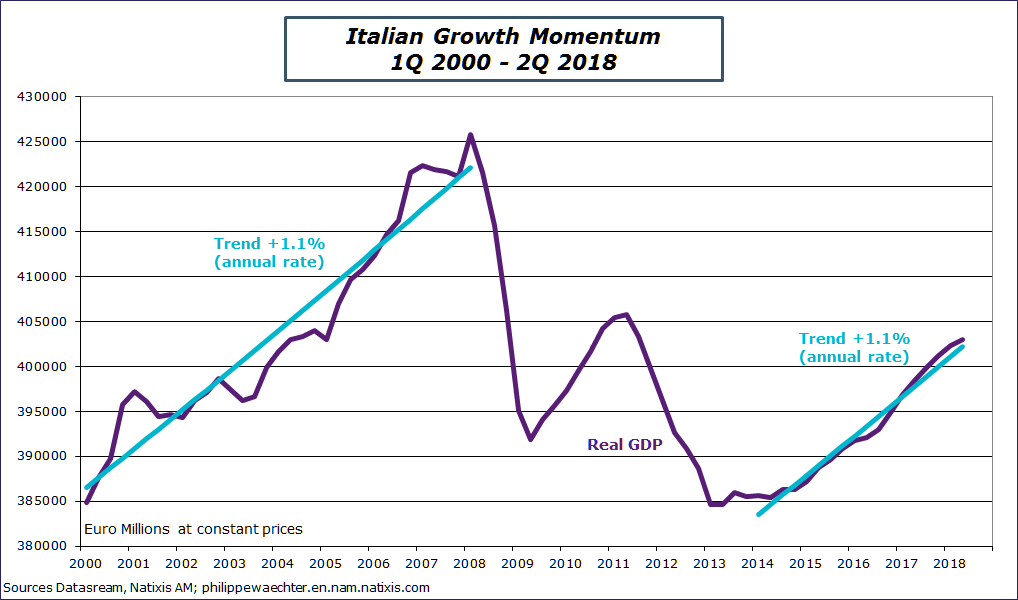

Public debt did not decrease as a result of this austerity policy, but the political consequences were severe. When we look at the Italian economy’s performances, it is not surprising that the country looked to more radical solutions. The policy implemented in 2011/2012/2013 was disastrous and led to a severe drop in income. There are of course other reasons, but the performance from the Italian economy probably goes a long way to explaining the current political situation in the country, although the populism issue obviously goes far beyond Italy alone.

What should we make of these policies 10 years on?

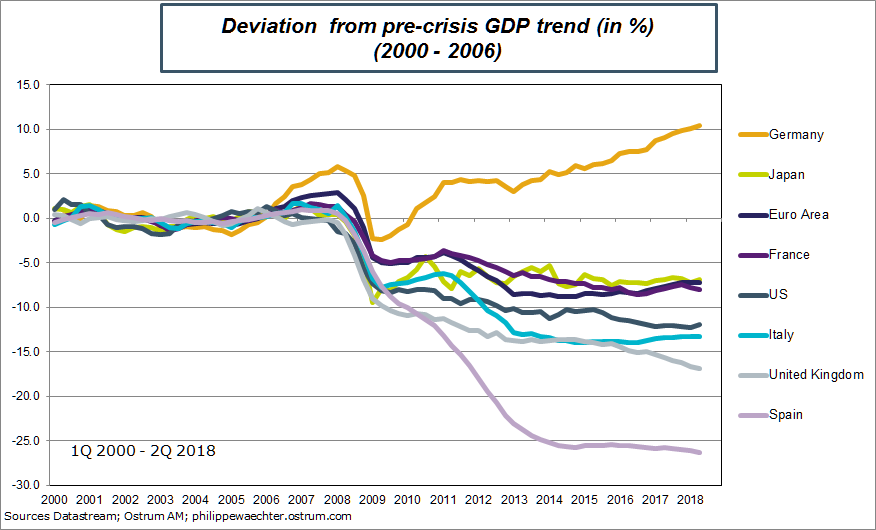

The 2008 financial crisis has incurred a permanent cost for virtually all western economies, as shown when we compare the actual performance from each economy to the trend it would have displayed had the crisis not taken place. I eliminated the last year of growth 2007 from the calculation, as it is often somewhat excessive as compared to the past, and would have skewed the result by pushing it up.

The cost of the financial crisis is huge: in the second quarter of 2018, euro area GDP was around 8% lower than it would have been had the financial crisis not taken place, and the figure is the same for France i.e. GDP would have been 8% higher in France if the country had remained on its pre-crisis trend. The difference is even more startling in Spain, the US and the UK, where growth was very robust before the financial crisis, while only Germany is enjoying higher growth than before.

When we look at the chart, we can see that countries are not converging back towards the past trend i.e. growth is weaker and is not recovering the momentum it previously enjoyed. This is one of the major disasters of the post-crisis period: growth is weaker and is not showing any signs of picking up, so we will never make up what was lost.

Does this raise fresh questions?

This situation obviously raises fresh questions. Social institutions have been shaped by growth since the Second World War, so slower growth weakens them. I made an interesting calculation for France for the pre-crisis period i.e. right from the start of the 1980s: the public debt/GDP ratio stabilized when growth stood at around 3%, while public debt spiraled when the French economy was only growing at on average 2%. In other words, the social system needed growth of 3% and the economy could only provide 2%, so public debt was used to make up for the shortfall. Trend growth is now weaker, so we need to find a way to adjust social institutions to stabilize the entire system. The answer could be stronger sustainable growth but growth is hard to come by.

When institutions are weaker, companies play a greater role in driving macroeconomic momentum, which in many developed countries meant that value-added disproportionally benefited companies to the detriment of employees and their wages, tipping the scales in favor of income from capital to the detriment of income from work. Income distribution has tended to shift further in favor of the richest portion of the population (top 1% of incomes), although France has been relatively unaffected in this respect, as shown by the recent report on living standards from French national statistics office INSEE (INSEE Première “Les Niveaux de Vie en 2016” September 11, 2018).

The labor market looks different too. The share of fixed-term contracts as a proportion of new contracts rose by 6 points in 2009 from 77% to 83% and will never return to the relatively stable levels enjoyed before the financial crisis. In the US, the proportion of men aged between 25 and 55 who no longer work is around 15%, despite the fact that this group makes up the core of the labor market. Those on lower incomes have several jobs as those on the lowest wages cannot make ends meet. And in the UK, we have seen the development of zero-hour contracts, adding a whole new dimension to job insecurity.

Inflation momentum has also changed

The other major observation is that developed countries are unable to spur on inflation. Apart from the UK, average inflation in developed countries was lower than the 2% target generally set by central banks across the period from January 2009 to July 2018. The current cycle in the US is the second longest since the Second World War. The inflationary pressure that we should have seen did not emerge. The current situation is not like the 1960s (longest cycle) when very strong productivity gains absorbed additional costs, and productivity is very weak across the board. The recent rise in inflation is still fairly limited and the Fed is not yet at a stage where it must pull out all the stops to curb inflation. Costs have been so severely limited that they do not even materialize when the cycle lasts a long time.

This lack of inflation is worrying for central banks, whose scope has been described pretty accurately by Taylor’s rule, which states that the Fed’s rates are dictated by economic activity (shortfall between real and potential output) and inflation (different with target inflation rate). Growth is weaker than before and inflation falls systematically short of its target, which means that central banks have much less reason to tighten monetary policy.

This explains why it is so difficult for central banks to move away from their very accommodative strategies – if they tighten too quickly when there is no inflation, they may well hamper economic activity, so they need to wait for inflation to materialize. Yet this is taking too long so financial imbalances – resulting from monetary accommodation – have time to emerge. The central banks are in no hurry to act and the ECB confirmed this stance last week at Mario Draghi’s press conference.

This means we will have to get used to very low interest rates for quite some time to come.

However, is monetary policy questionable?

Yes, it obviously is as despite very accommodative policies, no-one feels that the economy is all easy going.

Two criticisms are often levelled:

The first is that these accommodative strategies let major financial imbalances emerge, often in the shape of a bubble, which itself is seen as the beginnings of the next financial crisis. And this is where the real difficulty lies – more restrictive policies are required to address these bubbles but this means taking the risk of hampering growth and jobs, which is clearly not the right path to take. Herein lies the crux of the problem for central banks. To get around this point, many will say that monetary policy was too accommodative, but this type of analysis is often made after the fact when the dust has settled and things have resumed their natural order. We will need to get used to dealing with greater imbalances than we were previously used to.

The other major development is that banks have had more restrictions placed on them, but shadow banking has developed and gained ground very quickly. Shadow banks’ financing operations are not subject to such tight control and this potentially creates a source of weakness for the entire financing system.

One last point worth making is that banking regulation has become considerably tougher since the 2008 crisis, with two effects: firstly banks are now better equipped to deal with potential shocks; secondly now that things are going better, pressure to reduce is stronger, as is the case for the US for example.

So why does no-one feel like we really got over the crisis that took place 10 years ago?

The financial crisis 10 yeas ago is not the only watershed we have seen over the past decade. All eyes focus on the 2008 crisis as everyone thinks that we just need to get things back in order to return to the prosperity of old, and this is the idea at the back of our minds when we declare that interest rates are too low and that the “normal” level should be close to pre-crisis figures. There is a belief that we can return to normal and that for such times as we do not move back towards this normality, then this is still an abnormal period for the economy.

However, the idea of a different macro framework makes sense and provides the basis for the secular stagnation hypothesis i.e. growth would slow on a long-term basis, with no inflation and with lower interest rates than in the past.

In view of lower output growth and the power balance that works in favor of companies to the detriment of employees, this theory makes sense.

However, we can see that this explanation is inadequate to understand the unease still felt about the financial crisis.

There are certainly two further explanations worth exploring.

The first is that the geographical breakdown of output has been completely upended during the past decade. Countries that drove post-war growth have not enjoyed an increase in industrial output over the past ten years: industrial output gained 2.3% in the US between the first half of 2008 and the first half of 2018, while it plummeted 11% in Japan, 3.3% in the euro area and 8.3% in France. Robust volume-based industrial momentum is no longer the sole preserve of developed countries. The world index soared 22.4% primarily on the back of a twofold jump in industrial output in Asia excluding Japan over the past 10 years, soaring 98.3%.

This means that economic momentum in developed markets relies primarily on services, but making productivity gains is extremely difficult in this sector i.e. it is more difficult for western economies to generate a surplus.

As Daniel Cohen suggests in his latest book, there are no economies of scale in many service sectors, so it is difficult to generate major productivity gains over the long term.

The other explanation is the technical revolution, and there are several points worth raising on this aspect.

The first, which follows on from the previous paragraph, is the question of who benefits from any potential productivity gains? Is it the application that locks in these gains when in fact local services are moving towards a free model? As Daniel Cohen notes, the consumer behind his/her computer screen does not replace the person at the counter but rather the software creates this change. So the entire model and all our reference points are changing. As Cohen states, let’s hope that a way can be found for innovations and jobs to fit together as a result of artificial intelligence.

The other remark is that new technologies mean that companies’ organizational set-ups need to be reviewed, particularly in the corporate setting. The structure that emerged during the 30-year post-war boom in France no longer works, so companies’ organizational arrangements must be revised to take on board these technological shifts.

This is what happened when electricity became widespread: companies had to take on board this change by adjusting the way they worked in order to generate productivity gains, otherwise gains were weak. They only staged real productivity gains when they took this change into account: factories were then designed and built to use this new energy source, and this was a real revolution.

Our organizational structures and our companies as a whole have probably not yet entirely grasped the full consequences of this technological watershed, especially in the way companies are managed. The set-up of the factory was the key question during the switch to electricity, but in today’s service-based economy, the way management operates is the key factor, and there is still a lot of work to be done in many sectors.

The economy today consists of these three key factors, with these three major shifts. A new model has not yet developed, which is why the situation is tricky and there is still an uneasy feeling that the crisis is not over.

The financial crisis overturned the old economic model in the west, and the new model that still needs to be developed will be very different to the old one… and there is still a long way to go in western countries, which can no longer rely on the industrial success that made their fortune.

Posted in French on Monday the 17th

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog