This post is available in pdf format My Tuesday Column – 9 October 2018

Jair Bolsonaro has come out in the lead in the Brazilian presidential elections with 46%. Looking beyond his very divisive views on certain issues in Brazilian society (status for women, LGBT), on the Paris Agreement and the corruption of previous governments, along with his aim to end Brazil’s endemic violence by allowing Brazilians to take up arms, are there any economic foundations for his likely victory? (see here the Brazilian context of these elections)

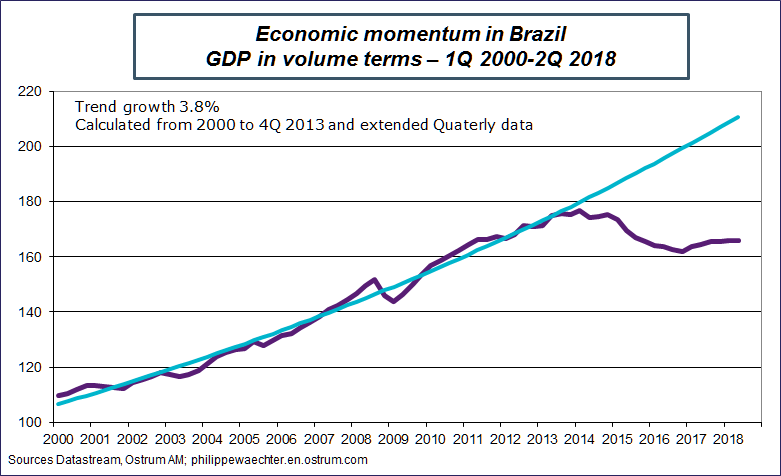

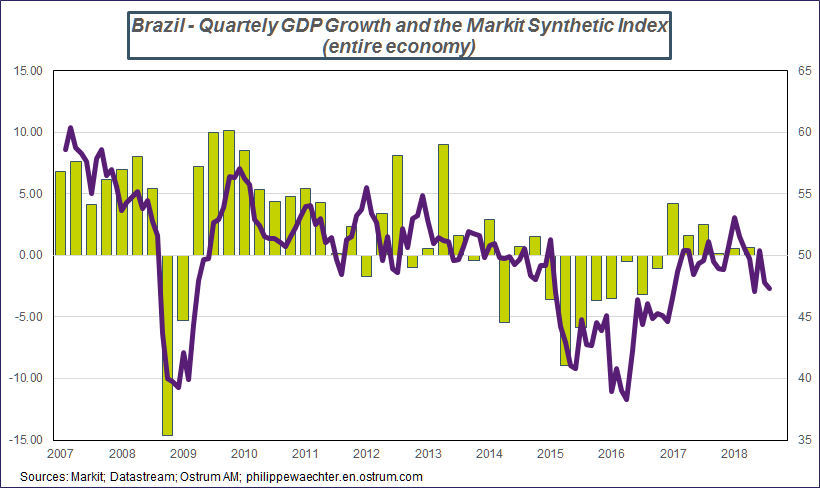

This victory has very clear economic explanations. The Brazilian economy has been suffering since 2014 and the collapse in commodities prices. The recession over 2014-2015 and 2016 lasted a very long time, and was followed by a lackluster recovery, which was more of a stabilization than a real rebound. GDP in the second quarter of 2018 still fell 6% short of the 1Q 2014 figure.

This drastic situation can be attributed to two factors. The first is the country’s high dependency on commodities. Brazil enjoyed a very comfortable situation at the start of the current decade when China became its primary trading partner. Opportunities increased and commodities prices soared, so revenues were buoyant and did not encourage investment, creating a phenomenon known as Dutch disease, whereby commodities revenues were such that there was no incentive to invest in alternative businesses. But when Chinese growth began to slow and commodities prices took a nosedive, the Brazilian economy was unable to adapt, so it seized up and plunged into a severe recession.

The other factor is that Brazil devoted hefty financial resources to financing the football World Cup in 2014 and then the Olympic Games in 2016, so in a country with a massive current account deficit, this put a lot of pressure on financing. Funding for public infrastructure replaced investment in production, thereby making the country’s Dutch disease even worse.

The Brazilian population has paid a high price for the country’s brief moment of glory.

Were jobs and purchasing power hit?

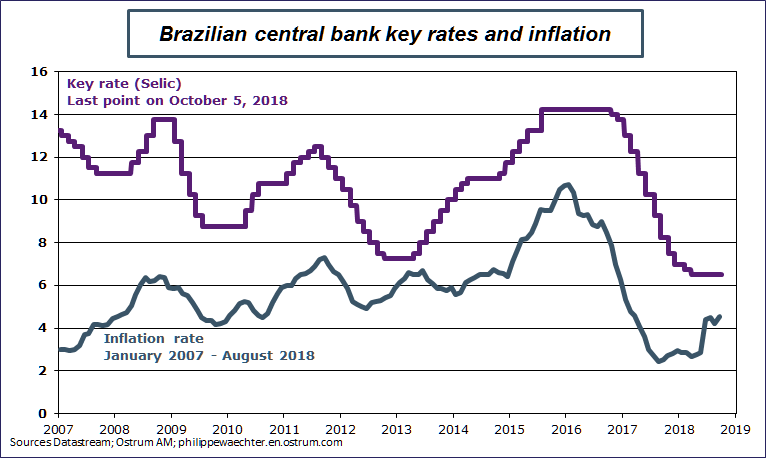

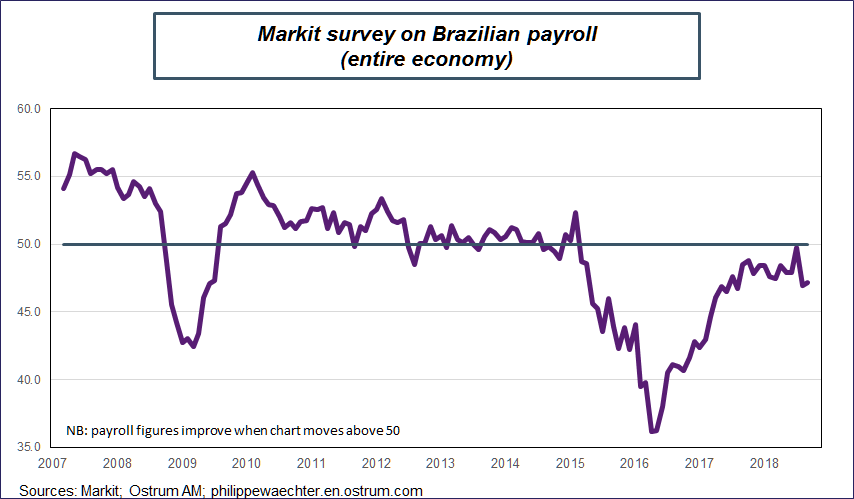

Yes – the job market contracted and inflation stepped up, and if we look at the Markit survey indicator, employment has not returned to 2015 levels, especially in for services, while jobs have stabilized in the manufacturing sector over the past year, albeit at a low level. So Brazilians are still paying for the recession.

An in-depth analysis of these data – a long recession with no real recovery, higher unemployment and a collapse in purchasing power – provides a greater understanding of why Brazilians decided to oust the ruling party, although this does not justify the choices they have made.

What can we expect for the Brazilian economy in the short term?

The Brazilian economy is still very shaky and the latest surveys suggest that recessionary risk remains high.

More broadly speaking, the slowdown in the world economy will not help drive economic momentum, while in the commodities sector, only oil prices are on an upward trend. The new president has a tough job ahead as the country has very high expectations, but Brazil is not the US: it is no longer a powerful economy and must first rebuild, which will be a long drawn-out process. There is a risk that change will not be fast enough to keep Brazilian voters happy at a time when the authorities are also taking a tougher line to maintain law and order.

The latest report was resolutely positive, as payroll stats have been rising by figures very close to 200,000 per month over recent periods i.e. the past quarter, half-year and year.

Figures also outstrip growth in the working population, which points to a drop in unemployment.

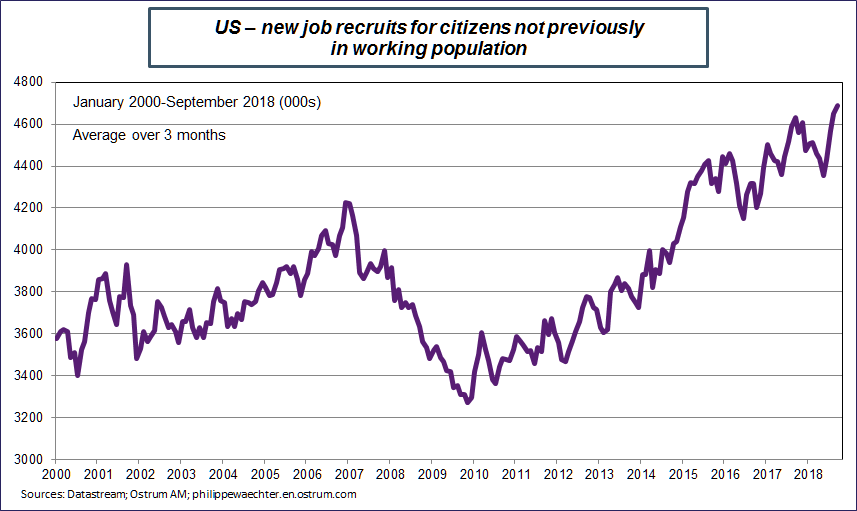

The key point to note here is the swift rise in the number of people who bypass the jobless statistics and go straight into a job. This means that job creation momentum is creating an incentive and there is a widespread feeling that everyone can find a job – even those outside the job market – and here it’s a definite case of yes we can.

Usually when there is a feeling that it is easy to find another job, people are back in the market and the unemployment rate increases in the short term. At the moment, Americans are looking to the job market and are feeling encouraged to go find a job straight away which is a fairly unusual situation.

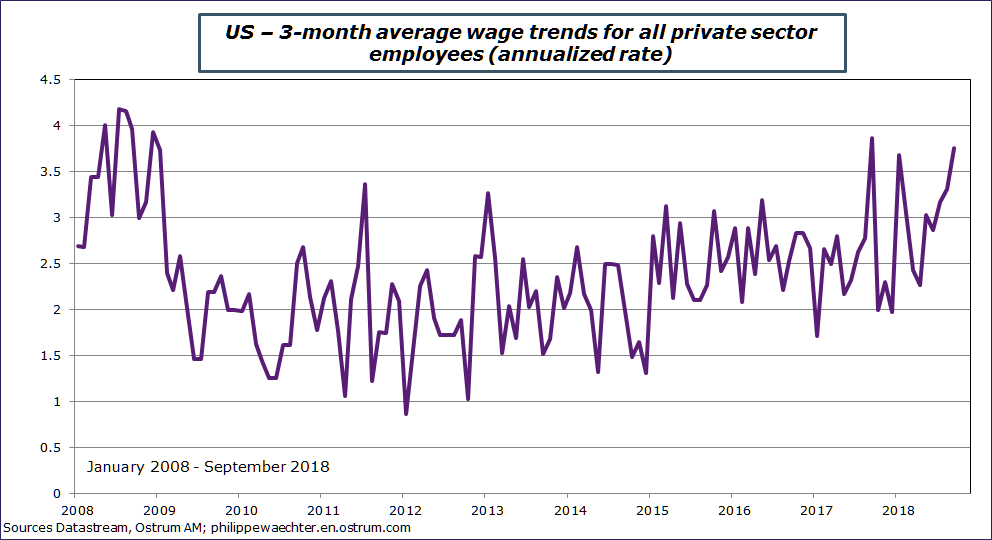

Yes, we are seeing the beginnings of wage pressure, with increasing periods of wage acceleration on the 3-month trend. It looks like the US labor market is gradually undergoing a shift and operating in a more traditional way, although the change is not entirely complete, as wages are still rising at a sluggish pace yoy and the trend has not returned to pre-crisis levels.

The Fed’s stance is consistent and investors are increasingly taking on board its message. It will continue monetary tightening to avoid imbalances emerging in the economy and spiraling out of control. This shift in perception pushed long-term rates up to around 3.2%

The way the Fed manages the current context will be key, as investors have so far believed that long-term rates would not move much as inflation projections are low. However, Powell changed this view when he clearly indicated that the Fed would “act with authority”, and this comes as no surprise as fiscal policy is fuelling domestic demand and triggering economic imbalances. The shift in opinion is reflected in market moves on 10-year rates.

Is this the start of a rise in long-term rates?

It all hinges on the Fed’s communication.

Cast your mind back to February 4, 1994 when the Fed hiked its key rate (it had been flat for several months) on the back of concerns over inflationary risks. This triggered a massive move on the 10-year Treasury, and European rates then followed in its wake, setting off some major and damaging consequences as a result of this surprise move.

This kind of situation would be bad news in today’s environment as the US real estate market has already started to adjust, so a further rise in mortgage rates – which are already very high – would worsen this trend.

It is up to the Fed to convince investors that it can manage the economy – by keeping imbalances on inflation to a minimum – and curtail the impact on the long end of the yield curve. The Fed must take swift and sharp action to rein in this risk… perhaps even sooner than investors currently expect.

Is growth gradually adjusting in Europe?

Yes, French statistics body INSEE reviewed its projection for 2018, which now comes out at 1.6%, while German economic experts revised their figure to 1.8%, more in line with survey indicators we have seen. Italy also reviewed growth projections, which helped scale back Italian risk.

What do you think about the Nobel prize for William Nordhaus and Paul Romer?

It’s an excellent idea. Nordhaus spent a great deal of his career working on highly useful research into the issue of resources and global warming, and played a vital role, which can be seen in the very clear research on his Yale website. Meanwhile, Paul Romer offered us a new view on the issue of growth, including the idea of endogenous technological change.

_______________________________________________

Translation of my Monday Column in French

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog