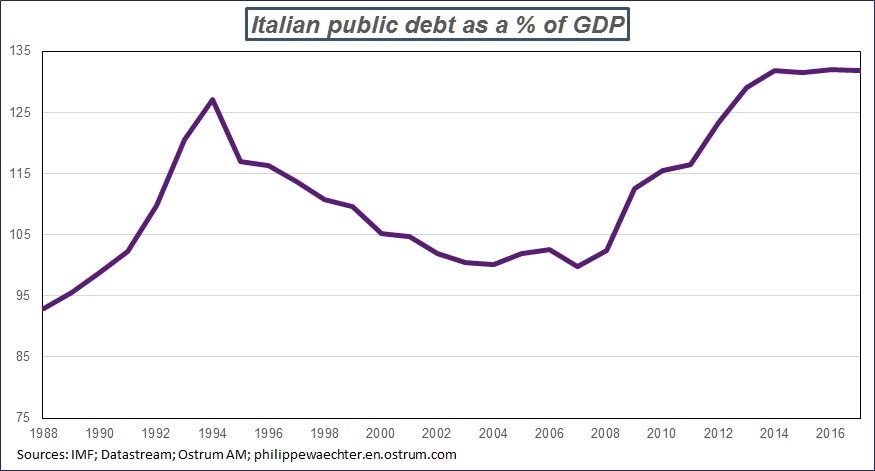

The European Commission has just told Italy to revise its 2019 budget plan: the deficit does not look excessive (2.4%), but the figure is deemed to be fragile as growth projections are overly optimistic….and with a government that emerged from a watershed vote, we should expect a certain degree of laxity on spending to boot. The government was not elected to do the same thing as its predecessors, i.e. there is a risk that the budget will spiral out of control and move above the notorious 3% of GDP threshold, which is incompatible with a stabilization in public debt. Italian public debt stands at close to 132% of GDP, well above the standard 60%, and this is not sustainable. Yet does a sustainable trend automatically involve a drastic cut in the public deficit? Maybe not.

There are a number of points worth raising on the budget/Italy/European Commission issue.

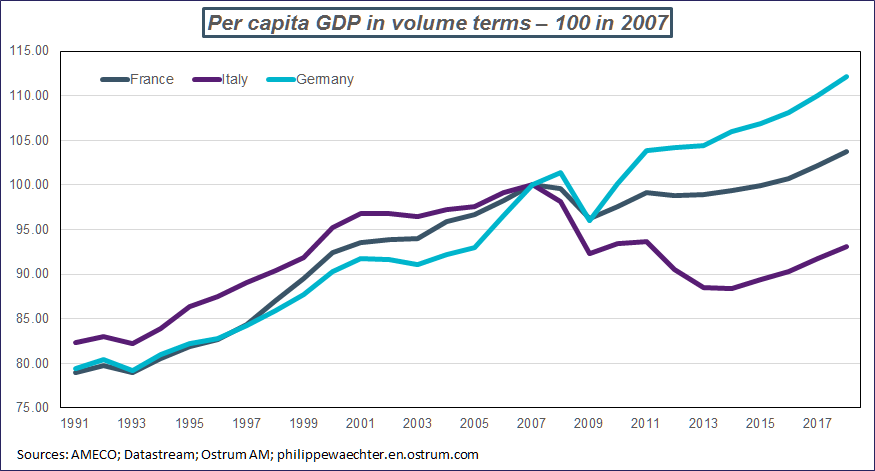

The first point, which is always important to bear in mind when we look at Italy, is its sluggish growth. GDP per capita in volume terms stands 7 points short of the 2007 figure and has grown by on average close to 0% annually since 1999. This is not the case for the other major European countries, and herein lies the real problem for Italy, along with its inability to return to a growth trend: this is the real crux of the matter.

The second point is that the measures put forward by the new government worsen the Italian budget deficit but do not seem likely to drive an acceleration in potential growth. The watershed government has not put forward measures to bolster productivity and set the economy on the path towards a more robust trend in the medium term.

The drop in retirement age in a country with a fast-ageing population points to a reduction in potential growth.

Meanwhile, the so-called citizens’ wage will afford many Italians fresh purchasing power, but well may we wonder if this will be enough to encourage companies to make massive investment to boost the pace of growth and productivity. Can the South act to drive growth in the North?

Lastly, tax cuts do not usually work miracles in strengthening productivity: they help improve microeconomic conditions but do not necessarily provide any real macroeconomic benefits, so the planned budget would tend to drag on growth rather than boost it.

The third point is on the Italian budget in itself. Accepted wisdom was that Italy needed to be more stringent to counter the surge in public debt, which stands at 132% of GDP.

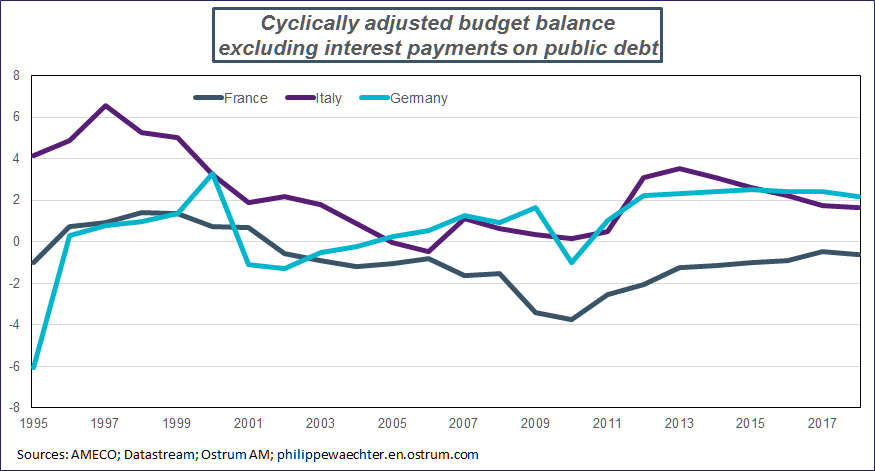

If we look back at the Italian budget since 1995 (start of AMECO data series), the country has been making the efforts required, and the cyclically adjusted budget balance excluding interest payments on public debt has systemically displayed a surplus. Does Italy need to take things a step further and generate an even higher surplus to curb its debt? This is what the Commission wants as it seeks more taxes and lower spending, when the problem really lies in the country’s inadequate growth.

Italy has been more disciplined than Germany since 1995, so does it need to be even more meticulous still? The sharp swell in the surplus after 2011 did not have a positive effect on growth and did not turn the public debt trend around. So when it comes down to it, fiscal discipline does not mean a reduction in public debt if economic activity collapses.

This is the real challenge for Italy and the Commission is wrong to focus on the deficit: the lessons of 2011/2012 have not been learnt. Fiscal discipline has not led to a reduction in public debt in the past, as growth had been hampered by government measures to address the imbalance in its public finances.

The Commission now wants to cut back the Italian public deficit at any cost, and risks creating a similar situation to that seen at the start of the current decade i.e. a downturn in growth without a reduction in public debt.

The real difficulty is that proposals put forward by the coalition government cannot drive a decent growth trend in the long term.

So we should expect somewhat unproductive talks over the weeks ahead between the Commission – which is focusing on discipline at any cost – and the Italian government, which will want to impose measures that will not lead to an improvement in Italian growth. All the while, the threat of sanctions from the Commission will only serve to make this standoff worse. This unusual episode in EU history reveals the limitations of Brussels’ rule, as the body’s set-up does not provide for a situation when the bloc sits down together, addresses Italy’s real problems and works together to find a solution for the country to return to its former glory.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog