The current epidemic crisis is the result of a massive health crisis that would have disastrous consequences without state intervention, and governments’ role here is to curb the extent of the disaster and stagger the cost out over the long term.

In China, Europe and now California, governments have resorted to lockdown measures to try to halt the spread of the virus. Yet the cost of these moves is very high, as they mean freezing activity in several business sectors, and growth is set to slow sharply in a very large number of countries.

In this situation, the role of economic policy is to steer our economies through this trying period without jeopardizing their very fundamentals.

Yet the million-dollar question still remains the length of the crisis. Will it be short enough for damage to be limited and the economy to quickly get back on an even keel? Or will it last longer and risk compromising the economy’s ability to get moving again?

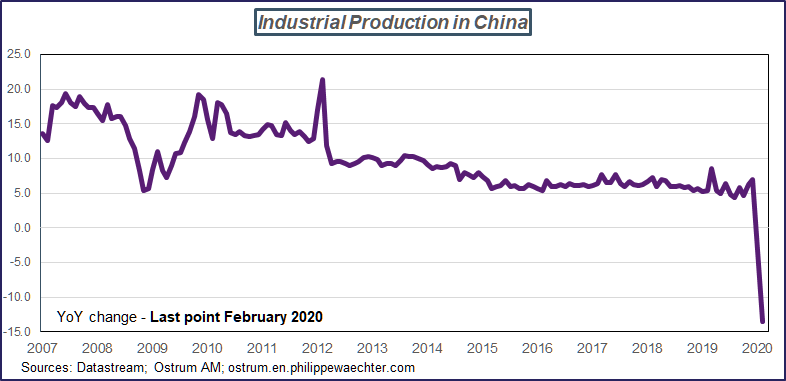

When the largest cog in the globalized economy is struggling, then there are extensive and long-lasting knock-on effects. China declared the emergence of the coronavirus on December 14, while the World Health Organization (WHO) was alerted to cases in Wuhan on December 31. The Chinese economy is the most dynamic for manufacturing and the country is the largest exporting country worldwide. So when the Chinese authorities imposed lockdown on January 23 and stricter quarantine on February 17, the economy ground to a halt. February’s manufacturing output reflects this situation, with a 13.5% plunge yoy after a 6.9% gain in December 2019. The Chinese economy has staged the fastest manufacturing growth over the past 20 years, so all – or almost all – manufacturing processes worldwide include a Chinese element, which means that the current situation has very direct impacts.

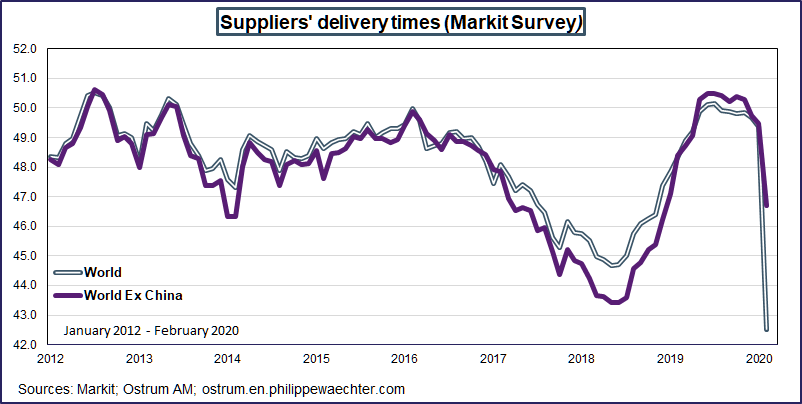

Applying the brakes to China’s economic activity means putting a drastic curb on its exports and world economic activity as a whole. February’s Markit surveys show that supplier delivery times have increased massively worldwide, including in China. Products usually manufactured in China are no longer making it to production lines elsewhere in the world, so vehicle and electronic equipment makers, as well as aircraft manufacturers and producers of other manufactured goods are being directly affected. These companies have had to dig into their reserves in February, but they will not be able to continue to do so to the same extent in March, and so output is set to decline across the board.

The number of coronavirus cases is no longer increasing in China, but economic activity has not entirely resumed, so supply coming out of China is not about to spontaneously return to pre-epidemic levels. In Wuhan and the Hubei region, precautionary measures still apply and authorities are watchful to ensure that they do not slide back into the previous disastrous situation. Other less affected regions are not subject to the same restrictions and can get back on the path to growth somewhat sooner.

Contagion to other countries of Asia is more restricted. Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan and Taiwan have swiftly kept epidemic risks in check, and spread has been limited, as the pattern in each of the countries has not followed the profile seen in China. However, there will be a hefty economic impact as these countries are dependent on neighboring China.

Activity slowing down already in Europe and the US

The situation is different in Europe and the US. The epidemic took root in mid-February in Italy with full lockdown since March 9, and the situation is deteriorating in the US, with Donald Trump declaring a state of emergency on March 13. Meanwhile, the governor of California has just announced lockdown for the entire state, which is the fifth economic power worldwide, just ahead of France and the UK.

Unlike in Asian countries, contagion in developed countries – apart from Japan – is following the pattern seen in China and then Italy, with a time lag. With a lag of between 5 and 15 days, France, Spain, Germany, the US and the UK are following the configuration seen in Italy. But the curve in Italy has not taken a downturn yet. We are seeing major inertia and strong determinism in western countries, which are all affected indiscriminately.

Countries are suffering a threefold impact on business.

1 – We have already seen an impact from the halt to the Chinese manufacturing sector’s operations. Activity is decreasing and lockdown measures are further exacerbating this trend. Employees are no longer able to get to work, which is halting economic activity. In the very short term, machine capital cannot replace missing employees. This slowdown is a major hindrance to world trade, which has decelerated sharply since the start of the year.

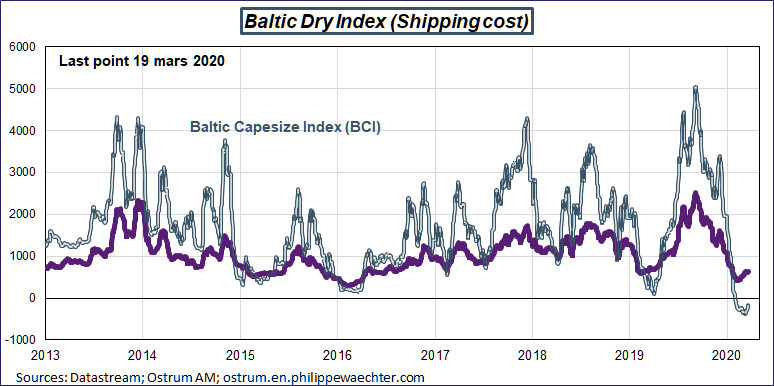

2 – The second source of weakness is the halt to movement, whether the trade of goods – prices for sea freight have plummeted since the start of the year – or personal transportation, as no-one wants to go to Asia and no-one is travelling out of Asia. The situation is very challenging for these transport sectors, with airlines sometimes suffering disastrous difficulties. The key challenge now is stopping the virus moving around, which has an instantaneous knock-on effect on tourism and any related businesses i.e. restaurants, hotels, leisure. Tourism accounts for 11% of GDP in Spain, so a collapse in this sector is a major worry for the country’s economy.

3 – The third factor is lockdown and the closure of schools. This makes for a very direct impact as employees who work with machines in the product manufacturing process are no longer at work as they are looking after their children, thereby hampering output. The effects of lockdown measures go far beyond school closures, as stores are also closed and those who work there have to stay at home. Restaurants and bars were already hit by the drop in tourism, but they are now closed, while cultural and sporting events of more than 50/100 people are banned. Social spending – all spending in places of social activity – is plunging. Domestic momentum is no longer playing its usual role in driving growth, and household spending is restricted to vital expenses – rent, telephone, internet, electricity, etc. – and food shopping. Everything else is postponed as stores are closed, but also as households are delaying their spending due to the current uncertainty.

Demand is usually dependent on export trends and the strength of domestic demand, but it is now on a weaker trend and failing to provide clear support for growth.

The process will be longer than expected

The impact of the shrinkage in China’s economic activity is sending shockwaves across the rest of the world, with the ripples intensifying when they make it to Europe and the US. The slowdown is further exacerbated by public authorities’ measures, particularly lockdown moves, making for a double whammy of external and domestic economic shocks.

This situation is also combined with massive disorganization as countries – now much more integrated than at the time of the SARS crisis in 2002 – are affected at different times, so each economy is hit both by world trends and its own individual economic cycle.

Even if the situation were to improve and uncertainty were to scale back, it would still take a long time for countries to get back to normal, and it would take even longer to stage global coordination resulting from the globalization of economic activity.

This is all the more true as there is no international economic policy coordination, and in this respect, world dynamics are much more disparate than in the post-Lehman period in 2009. It is hard to envisage or expect a G20 meeting equivalent to the London summit in 2009, when vital collective decisions were made to drive a return to growth.

However, the scale of the shock will hinge on the length of lockdown measures. We all want to believe that this quarantine period will be limited and that it could end well before the summer, and this is the implicit assumption in the economic policy measures taken. However, if there is no solution to the vital health conundrum over the weeks ahead, then the cost of the crisis will grow.

The current consensus is that lockdown could end in France at the end of April, yet epidemic modelling suggests that this containment period could last longer, until such times as a vaccination is found or herd immunity develops. These models suggest that the number of infected patients could stabilize while lockdown measures are still in place, but the end to lockdown would trigger an uptick in the number of cases.

Herein lies the real difficulty in this period that is marked by immense uncertainty as to when the situation may at last improve on a lasting basis. For such times as we do not know for sure when the epidemic will end, restrictive measures will continue. The economy is not about to get back to its normal pace for quite some time.

The crisis will be severe and economic activity will contract

The disruption to production systems we have witnessed makes it tricky to draw up projections on the economy’s future trends, and a number of factors should be considered in this respect.

Firstly, first quarter economic activity figures are swiftly being downgraded. In France we note the Banque de France’s downgrade to growth from 0.3% to 0.1%, and the figure could turn out to be even lower and closer to 0%, as March was the most severely affected month. The real question mark now is on the second quarter. Estimates are being downgraded across the board as production facilities have ground to a halt (Renault, Peugeot, etc.) and aircraft are parked. Chinese manufacturing output figures for February should help guide projections and we should expect declines of between 2% and 10% on an annualized basis over the three spring months: this is a vague estimate as we do not yet have clear information.

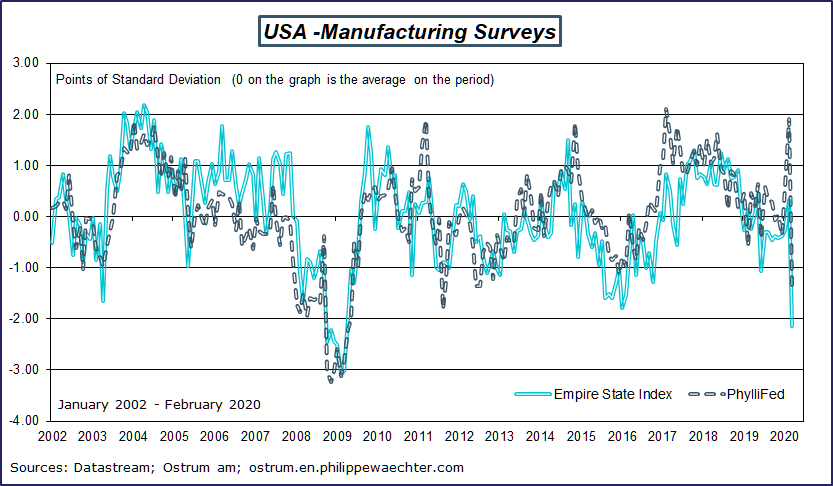

The only available information is the dire decline for the ZEW survey in Germany, and the New York and Philadelphia Fed surveys.

The drastic shock resulting from an epidemic has been modelled and suggests that it could involve a GDP contraction of between 2% and 6% depending on assumptions on lockdown and how demand trends.

If the epidemic affects the population but does not require lockdown, then the decline in economic activity could come to 1% to 2% over a full year. Some staff cannot work and the economy’s production process is disrupted for the long term. A quarter of decline – even if it is severe – could then be offset by a gradual adjustment.

If the lockdown option is confirmed and schools are closed for several weeks, then the economy’s production role is disrupted over the long term, and economic activity could decline by 3-4%, or even further depending on the length of the lockdown measures.

The end of lockdown is followed by a phase of improving activity, but questions remain on the pace of ensuing demand. In light of the uncertainty generated by the crisis, demand cannot increase as quickly as expected, thereby curbing the extent of the rebound.

In light of lockdowns in France, Italy and Spain, the euro area economy will be in recession in 2020, probably to the tune of around 2%, while the US will also slide into recession. The halt to activity in California with its lockdown will act as a severe drag on US economic momentum, and my estimate is also for around 2%.

In light of the temporary contraction in economic activity, economic policy must rein in the risks on the economic system. With the production system at a halt, there is no question of driving demand via additional spending, so the goal for economic policy will be to keep production facilities in working order.

Very accommodative fiscal policy to get over the worst

In the euro area as well as in Denmark, governments’ economic policy is essentially about doing whatever it takes to get through this upheaval as safely as possible. With economic activity at a halt, the entire production system is at risk, and it is essential that we prevent companies from going bankrupt just because of this unusual situation, as this would damage the economy over the long term and hinder its ability to recover swiftly when the epidemic is past.

Typical examples of measures taken in this type of situation are those already rolled out in France, with postponement of employer social security contributions and taxes, guarantees of cash loans to companies and the government covering the cost of partial unemployment. The first aspects aim to reduce imbalances for companies as much as possible, so that they do not suffer instantly as soon as their revenues plummet: they need to be able to hit the pause button during this difficult time. The government’s moves to cover the cost of partial unemployment will help companies keep their staff and not be forced to make them redundant: this means that when the recovery does occur, companies can resume work immediately and not have to embark on costly recruitment processes. This is what Germany did in 2009 for 1.5 million staff in an approach that turned out to be effective.

Germany is not taking exactly the same strategy. There was no lockdown, but the economy is hard hit and the government is willing to support the economy and businesses, even if that means temporarily waiving its usual fiscal targets.

The stimulus program in the US could prove to be ineffective due to the type of crisis we are encountering, which is characterized by severe supply constraints. Simply ploughing money into providing purchasing power is not very effective, particularly if California is not the only US state to adopt lockdown measures. Congress is currently waving through measures that would ease the situation for companies, although they are not on a par with moves made in Europe.

The immediate effect of this situation is a stellar increase in public deficits, which – in light of expectations on the activity profile and governments’ spending pledges – will probably surge beyond 5% of GDP. So public debt is set to soar swiftly.

Monetary policies covering the cost of adjustment

Monetary policy will have a crucial role to play, alongside measures taken by the various governments. Monetary authorities have all adopted similar strategies aimed at limiting costs to help get through the period of transition.

The first step is to reduce funding costs, with the Fed slicing its key rate to a range of [0%; 0.25%] and the Bank of England cutting its base rate to 0.1%. Rates in the euro area were already very low, but this did not stop the monetary authorities in the zone cutting back the cost of bank lending to companies.

The second type of measure is to reboot or extend asset purchase programs. The Fed has stated that it would buy $500bn in T Bonds and $200bn in MBS, while the Bank of England is resuming its QE program for a total of £200bn and the Bank of Japan is also ramping up its purchases. The most interesting example is the euro area, where the ECB indicated on March 12 that it would extend its QE program by €120bn out to end-2020 (in addition to the more than €20bn on a monthly basis and reinvestment of payments from maturing securities). On March 18, it decided to set up a new pandemic emergency purchase program – PEPP – of €750bn including assets eligible under the existing asset purchase program.

The ECB’s intervention reflects the bank’s determination to stand with governments that are set to issue considerable amounts of public debt, and this will keep interest rates low across the entire euro area.

The ECB’s entire firepower will come to around €1,000bn for 2020, with the central bank stepping into the market’s shoes for public debt. This may be a stabilizing factor for the risky asset market, acting to coax investors into these assets.

Conclusion

The current epidemic crisis is the result of a massive health crisis that would have disastrous consequences without state intervention, and governments’ role here is to curb the extent of the disaster and stagger the cost out over the long term.

In China, Europe and now California, governments have resorted to lockdown measures to try to halt the spread of the virus. Yet the cost of these moves is very high, as they mean freezing activity in several business sectors, and growth is set to slow sharply in a very large number of countries.

In this situation, the role of economic policy is to steer our economies through this trying period without jeopardizing their very fundamentals.

Yet the million-dollar question still remains the length of the crisis. Will it be short enough for damage to be limited and the economy to quickly get back on an even keel? Or will it last longer and risk compromising the economy’s ability to get moving again?