Swiftly expanding public debt to support macroeconomic adjustment is entirely warranted to tackle the pandemic, and this process is facilitated by mammoth intervention from the central banks. Meanwhile, low interest rates make this debt sustainable over time. However, this set-up is not viable for the long haul and high public debt figures will be a hindrance for economic policy.

Looking beyond the usual precautions, canceling debt does not look like a practicable option in the euro area. Only higher inflation would afford governments greater leeway and also come as a boon for the central banks, as they could finally ratchet up interest rates again.

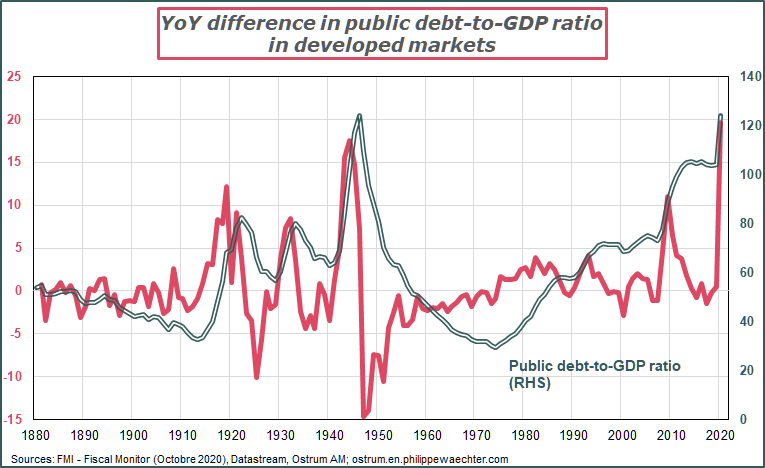

Public debt surged at an entirely unprecedented pace in 2020 as compared to past trends, with the public debt-to-GDP ratio soaring by 20 points in the space of a year. The 2008/2009 financial crisis looks almost insignificant in comparison to this scale of events.

If we look back at past figures, we observe that since 1880, public debt has been massively expanded when events call for the impact of a shock to be smoothed out over time. Funding is provided instantaneously, while payment is then spread out over the long term, with the overarching aim of shielding the economy from a drastic adjustment when the shock hits, such as during wartime – but also in the event of a health crisis. When compared with past events, the surge in public debt in 2020 is entirely warranted as countries seek to ensure that the effects of the macroeconomic adjustment do not hamper the current time period alone, while also positing that the current health crisis is temporary and not here to stay. So the belief in “getting back to normal” is the key factor underpinning this approach, and judging by past experience, this strategy has worked well.

The central bank’s role and the sustainability of public debt

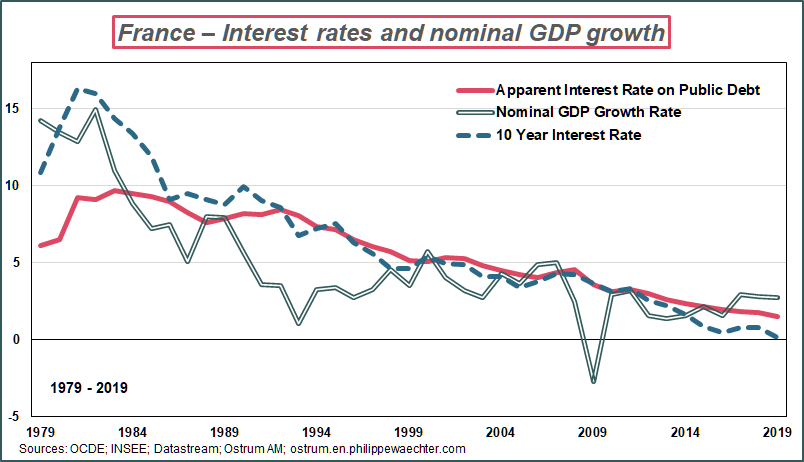

The unusual feature of the current period in time is central banks’ moves to purchase huge amounts of sovereign debt. So while natural interest rates are close to 0% as a result of excess savings worldwide, this trend is also further driven by central banks’ intervention. Nominal interest rates are therefore much lower than the economy’s nominal growth rate. This keeps public debt sustainable if the public deficit is not excessive. The primary budget balance (excluding interest payments), which stabilizes public debt as a % of GDP, must equal the difference between the apparent interest rate on debt minus the pace of nominal GDP growth, multiplied by the public debt-to-GDP ratio. If interest rates fall below the nominal growth rate, then the circumstances for sustainability of public debt hinge entirely on the primary budget balance. If the ECB keeps interest rates at rock bottom for a while to come and the economy trends towards a “normal” pace again, then the profile for public debt will only depend on the primary budget balance.

This is a crucial question in France as we have no idea how measures rolled out in 2020 – bringing the structural public deficit to over 4.5% of GDP – will be funded over the long term. On the chart we can see that nominal growth lagged interest rates for a long time, reflecting the major disinflation episode in the 1990s, particularly with the strong franc period, held dear by Pierre Bérégovoy. We can observe that the market interest rate took quite some time to adjust, pointing to the question of the credibility of French policy. Interest rates and nominal growth have only really settled into a consistent pattern since the euro area was set up.

This chart is very useful in measuring the credibility afforded to France by the creation of the euro area. Since the start of the ECB’s QE program in 2015, nominal GDP growth in France has been higher than the market interest rate (dotted line), but also the apparent interest rate (interest paid as a % of debt outstanding). So the ECB has a crucial role – and it is now governments’ responsibility to take the steps required to make public finances sustainable for the long term.

Public debt is historically high,

but with interest rates historically low,

the sustainability of public debt is preserved for the long term

However, this situation is in no way satisfactory, and central banks cannot pledge to keep interest rates at their nadir on a long-term basis on the back of increasingly sizeable interventions. So we cannot assume that the current balance between fiscal and monetary policies will take root for the long run beyond this short-term phase. Looking to another aspect, public debt is soon set to become a thorn in governments’ side. If the pandemic situation improves, then public debt will be perceived as lofty as the temptation will be overwhelming to get the economy going and get back on track to the pre-crisis trend. However, if the epidemic situation deteriorates, public debt will need to keep on increasing vastly, with the danger of doubts emerging on the effectiveness of economic policy. It makes sense to resort to public debt when a situation is short-lived, but when it takes root for the long term, this raises questions on credibility and requires other strategies to facilitate macroeconomic adjustment.

In other words, public debt is too high if the economic situation revisits more normal trends, and a number of options are available to cut back these figures.

Rolling out austerity policies

This approach involves cutting back the public deficit post haste to avoid further adding to debt. This strategy was adopted in 2011 and triggered a lengthy recession lasting six quarters between mid-2011 and end-2012, with disastrous effects in both Italy and Spain. It is never a wise move to roll out restrictive strategies in a fragile economy, when massive uncertainty hinders economic agents’ efforts to plan for the future. These difficult decisions – such as austerity – must be made when the economy is robust. When uncertainty is pervasive, the tendency is to hunker down and hold on, drastically restricting macroeconomic adjustments. Angela Merkel, who was instrumental in these decisions in 2011, has had a change of heart on this frugality.

The other point worth noting is that this kind of strategy would raise questions on the state’s management of economic dynamics. Most countries responded very swiftly to the health crisis in 2020, taking large-scale decisive action to ward off the risk of an economic collapse. This strategy worked fairly well, and the question now in 2021 is just how governments will continue with their intervention to smooth out the effects of the current situation, particularly if the pandemic risk worsens. Independently of austerity policies, macroeconomic adjustment still involves the issue of hefty public debt, so an abrupt ease-off in government intervention would hamper an already fragile economy.

The challenge for 2021 then will be the way that governments pursue their intervention to keep the economy on its feet, rather than swiftly scaling back economic policy.

Low interest rates afford some leeway in the long run

Olivier Blanchard (see American Economic Review April 2019) noted in 2018 that in the US, the nominal growth rate surpassed interest rates, thereby reducing the trend rate for the public debt-to-GDP ratio, all else being equal. This now applies across the board as a result of colossal central bank intervention. In Japan, the weighting of interest in GDP was less than 0.1 point of GDP according to the OECD. Active monetary policy affords fresh leeway to fiscal policy, and this is a possible solution, although I always struggle with the idea of extremely low interest rates for the long term being compatible with economic efficiency. On the one hand, this situation does not allow stakeholders to select only the most productive investment initiatives and on the other hand it fosters the emergence of zombie companies that only survive as they are propped up by overly accommodative financial conditions, without really guaranteeing economic efficiency.

Cancelling public debt

This idea is often mentioned as a result of mammoth central bank intervention. However, cancelling public debt is not permitted for legal reasons, while from a credibility standpoint, cancelling public debt is not a great idea either. In the chart on France on the previous page, we observed that the decrease in inflation had considerably slowed the pace of nominal growth for the French economy, but interest rates adjusted only sluggishly. There was no default, but rather the shift in economic policy was not instantly deemed to be credible (Axel Weber discussed this in the April 1991 edition of Economic Policy). So can we imagine the effects of a cancelation of public debt?

Looking beyond this question, it is also crucial to highlight the very specific features of the euro area.

In a country like the US or the UK, the treasury and the central bank are public sector entities, so consolidation of this portion of the public sphere could potentially help cancel some public debt issued by the treasury and held by the central bank. This move would deny the government the revenue usually paid by the central bank, but it is a possible scenario. However, the crucial stumbling block here is the central bank’s independence: in this kind of situation, its intervention would depend on the government’s action. This is already the reality of the situation at the moment during the current unprecedented pandemic, but we cannot envision this set-up continuing over the long term. Two heads are usually better than one when developing economic policy, and having an independent central bank offers just this. Cancelation of public debt is therefore not good news for the central bank’s credibility.

Additionally, this type of consolidation is impossible in the euro area. On the one hand, with the pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP) the capital key dictating the weighting of each country in the debt held by the ECB is not fully observed.

On the other hand, a joint and unanimous decision from all governments would be required to cancel out this debt, so French, German, Dutch and all other administrations across the bloc would have to agree to this on principle, which is highly unlikely. In the event of disagreement on this point, effectively making this move to cancel debt would sound the death knoll for the euro area. So this would clearly in no way be a wise idea.

Furthermore, if the idea is to replace debt resulting from the health crisis by debt for the ecological transition, then this means assuming that this substitution would not be disruptive for the economy – a bold assumption, even if we are convinced that the ecological transition is a necessary move. What would guarantee convergence towards a stable path?

A more standard macroeconomic adjustment

The post-shock upturn in growth has traditionally been the key factor in cutting back public debt. When public debt intensifies due to a war, reconstruction acts as a sufficient growth source to trim back the public debt-to-GDP ratio. However, one major exception to this was in Germany after World War I. The policy rolled out at this time did not have an effective impact on the economy, and the outcome was a social and political crisis.

In the period following the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the ratio stabilized without decreasing (see the first chart on page 1). The uptick in growth lacked the necessary muscle, as attested by the slowdown in productivity gains since this crisis. A recovery in economic activity is expected over the period that lies ahead, but it looks unlikely that growth will surge on a sustainable basis and move far beyond the trends observed before the pandemic, if we consider productivity gains. We can hope for growth to pick up the pace, but this does not look like the most likely scenario.

This implies that more robust growth will probably not be the way to bring public debt down, as it had been in the past.

Resorting to inflation

Higher inflation would be the appropriate solution. Governments relied on public debt as a tool to facilitate macroeconomic adjustment, with the public sector taking over management of the entire macroeconomy. However, this intervention is not sustainable over the long term, so another policy instrument is required, and in my view, inflation is a good fit.

This would step up both the pace and extent of financial repression, with more negative real interest rates, highlighting the need for the economy to come back to the fore. My premise is that the central banks will continue to intervene, but their inflation target – from all these institutions – will move towards the more ambiguous and less stringent target set by the Fed i.e. inflation moving towards 2% in the medium to long term. This means that inflation can run above 2% over the longer run without the central bank needing to intervene quickly.

Higher inflation would help drive more robust nominal growth despite lower real growth.

This would eventually also enable the central banks to break free from the restriction of zero interest rates on the short end of the yield curve, and very low or even negative rates on the long end, thereby affording fresh leeway for the monetary authorities.

The reason I focus on inflation is the parallel I draw with the 1974 crisis at the time of the first oil shock – a crisis I feel has similarities with the current episode. This period was characterized by a sharp swift surge in oil prices, dragging down profitability for a huge number of businesses, particularly in manufacturing. Resources had to be reallocated, particularly into services. The surge in energy prices was the trigger, but moves to index wages to prices drove higher inflation over the long run in the renowned price-wage spiral. Alan Blinder (The Anatomy of Double-Digit inflation in the 1970s in Inflation: Causes and Effects, R.Hall Ed, U.Chicago Press – 1982) noted that the surge in inflation facilitated these sector adjustments. Similarly, the shock from the recent health crisis has also reshuffled the cards, particularly in the services sector, prompting a reallocation of resources. Slightly higher inflation would facilitate the oft-mentioned adjustment generally observed during major crises i.e. sectors driving macroeconomic growth develop, at the expense of sectors that have been dented, such as the airline sector currently.

At the time of the first oil shock, wage indexation played a key role – a role it can take on again. It is also worth noting that the surge and subsequent dip in inflation in the 1970s and 1980s were fueled more by the government’s economic policy than monetary policy. Additionally after this type of shock, economic reconstruction requires renewal of potential growth. Incentives must be developed for the employed, and this could include more systematic indexation for the working population, and under-indexation of pensions for those who do not work. The transfer to the labor market would help drive the renewal of potential growth.

This shift towards a greater role for fiscal policy attests both to excessively low interest rates as well as the polarization of our global world. Concerns are now increasingly local and rely more on government policies. This phenomenon can be observed in China, with its import substitution policy, while Joe Biden is also expected to roll out an economic policy for the middle classes. So adjustments will be increasingly local.

Higher inflation could take over the role played by public debt as an instrument for macroeconomic adjustment.

This must only be temporary until such times as the economy can be set on a fresh path again.

__________________________________________

Tis post is available in pdf format