The economic cycle is only truly useful when it is regular enough to make the economy predictable. The Phillips curve provided for an assessment of economic cycles, but this approach is now becoming less applicable due to a changing labor market.

I recently attended a seminar that addressed the economic cycle, and the key question on this theme is not so much whether economic cycles exist but rather their regularity. We can always single out a trend that looks like a cycle.

However, economic cycle theory needs to make cycle trends predictable if it is to be truly useful. The cycle theory was developed on the basis of this point .

The success of economic cycle theories outlined by Kitchin, Juglar, Kuznets and even Kondratiev is judged only on the regularity and specific length of each cycle. The aim of these theories is to achieve greater certainty on the economy for the not too distant future, so if cycle theory does not provide some insight into future trends, then it has no real purpose as changes in direction at cycle peaks and troughs remain just as difficult to assess.

So the cycle emerges to offset to uncertainty

A predictable economic cycle makes it easier to implement economic policy to correct excesses and set the economy on the right track. So understanding the profile of the economy and the impact of any corrective measures means it is much easier to steer.

This idea that we could scale back uncertainty fueled the development of sophisticated models to predict the position in the cycle as accurately as possible, and then come up with the most effective economic policy moves to address the situation.

These arguments now seem to be a thing of the past

The economy

is now more global and the 2008 financial crisis overturned all western

economies’ adjustment mechanisms. Economic policy fine-tuning is tricky as we

do not necessarily know just where we are in the economic cycle. For example,

the Fed always seems pleasantly surprised that the US cycle just keeps on going

month after month, making it the longest ever cycle in the country’s history. While

on this side of the pond, the ECB is floundering as it should already have seen

nominal pressure and inflation converging towards its 2% target at this stage

in the cycle, but it’s a no show.

The economy remains cyclical as behavior has a lasting effect, but cycles are

no longer displaying the steady regularity we would like.

Using the Phillips curve to demonstrate

If we want further evidence that both the profile and the pace of the cycle have changed, we need look no further than the Phillips curve, which sets the economy’s real and nominal aspects side by side. This curve has traditionally been based on the inverse relationship between an economic activity indicator – unemployment – and a nominal indicator i.e. core inflation or wage growth.

This relationship was a crucial component in managing the economy for quite some time: economic growth led to a drop in the unemployment rate, and upward pressure on wages and prices . This is the Keynesian version of the theory from the start of the 1960s (Samuelson and Solow) that Friedman countered in 1968 stating that any drop in unemployment below its long-run trend as a result of accommodative monetary policy would only lead to additional inflation without keeping unemployment lower over the long term.

This relationship was relatively stable in the short term, making central banks’ moves easier to predict. This consistent relationship was taken on board in the Taylor rule, an economic policy guideline, which is actually just a specific version of the Phillips curve. This aspect meant that the Phillips curve could reduce uncertainty, which was all important and made it an extremely useful instrument in regulating the economy.

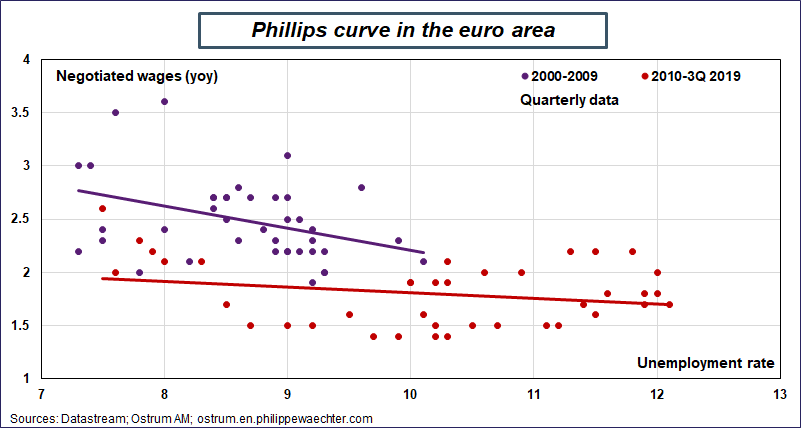

The chart opposite plots the Phillips curve in the euro area since the start of this century.

During the first decade of the 2000s (blue dots), the Phillips curve was as it should be, as the decrease in unemployment drove pressure on nominal indicators, in this case negotiated wages, with the cycle responding to the appropriate signals. This relationship can be shown by the blue line, which reflects the trend between the two indicators and shows a downward slope, as it should do. Since 2010 (red dots), the cyclical aspect that we usually associate with the Phillips curve has faded, even for the short term, and the red line denoting this trend is horizontal.

In a recent policy brief, Olivier Blanchard noted that the slope has gradually declined and has been flattening in the US for a long time, which looks consistent with trends observed in the euro area. The relationship no longer seems to have the required regularity.

Interpretation based on a labor market analysis

The economy changed after the 2008 financial crisis, and the shockwaves it set off had lasting effects, with growth displaying weaker momentum across the board. Changes on the labor market are probably the crux of recent shifts in the Phillips curve and the way it has flattened in the US as well.

David Autor discusses the idea that the labor market situation is not the same for the different skill groups, particularly due to competition from innovations.

Autor, and others after him, break down the labor market on the basis of both skills and the extent to which each worker may face competition from innovation. High skill workers support innovation and benefit from it, while low skill workers get by on the sidelines of the labor market, where work is insecure but does not require any specific skills, they just need to be willing to work even in poor conditions. Then there are medium skill workers (intermediate jobs), who account for a large proportion of the job market, and work on jobs requiring few or low qualifications: this group is directly hit by competition from innovation. This group breakdown is not flawless across the board but it can be seen in developed countries. As demonstrated by Reshef and Toubal on France (see below), the 2008 financial crisis probably accelerated this division.

The middle class portion of the labor market, which played a key role in the growth model 30 or 40 years ago, will now have to adapt to this new paradigm by hook or by crook, but yet it has no real preparation for this situation.

In a recent paper (link in French), Ariell Reshef and Farid Toubal expertly outline this situation in France. Jobs for unskilled or highly skilled workers are increasing, but roles for those with few or low skills are declining. According to this research paper on France, this class of intermediate jobs accounted for 62% of the job market in 2008 (table 2 page 36), and this portion of the labor market is suffering decreased negotiating power due to a declining number of jobs and lower trade union involvement.

This flags a real difference with the 1960s when trade union membership was higher and job growth came from these medium skill jobs. Wage pressure is therefore lower and companies face less need to adjust their prices to safeguard their margins, so there is less upward pressure on prices too. The market segment that posts high productivity can bolster corporate margins, while the market segment consisting of insecure jobs see limited compensation and no real pressure on margins. On intermediate jobs, pressure on margins is lower as wage pressure is low. Unemployment can decrease without nominal pressure growing. Upheaval on the job market could therefore be consistent with a Phillips curve that has lost its initial features.