The Macron presidency is finally going to be able to unleash its full momentum. Talks between the government and trade unions on the broad trends for forthcoming changes to French labor legislation have taken up a good deal of time over the past few weeks. The government decrees were announced on August 31 and will come before the French Council of Ministers on September 21: the President’s term can now really get started.

The government’s aim is to make the labor market more adaptable to change by altering certain aspects of labor law.

In this column, we will look at whether the labor market will react more quickly when economic activity improves, as hoped. The recovery in economic activity dates back to early 2013 in France, but private sector employment only recovered two years later. The government’s aim is to cut back this time lag to make the French economy more adaptable and overall more self-sufficient.

A more critical view suggests that flexibility is not the real issue behind the slow recovery in the labor market, but rather the application of austerity policies from 2011. Inadequate demand led to a drastic adjustment in employment. The French economy has not recovered the same growth momentum since the recovery in 2013, and employment is struggling to regain a reasonable growth trend. In this analysis, job market momentum has little or nothing to do with labor legislation but rather primarily hinges on demand, so flexibility is not a decisive argument in this case.

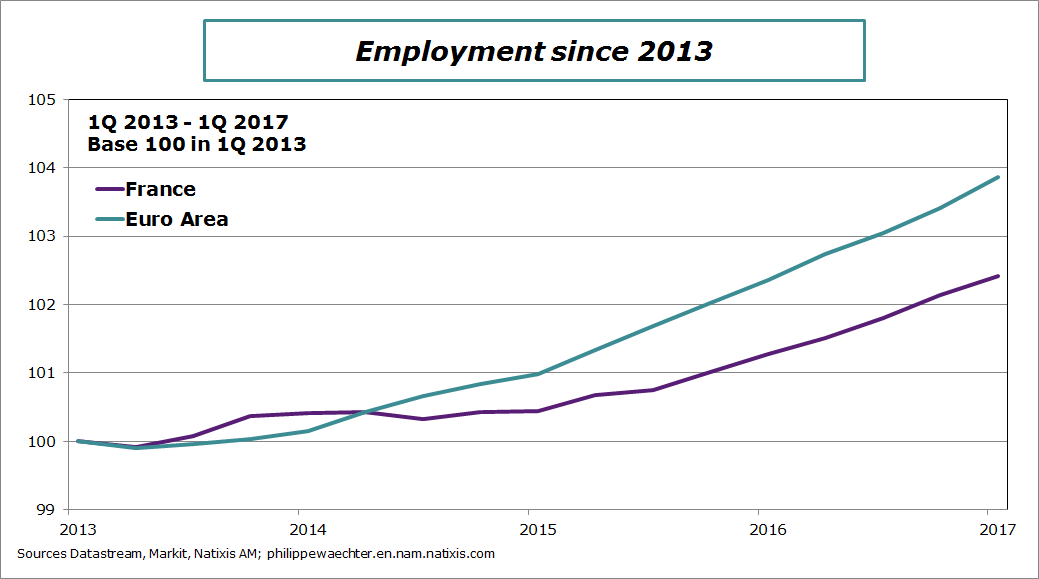

In my view, we need to look at a combination of these two complementary assessments. The economy in France and those in the euro area as a whole were hampered on a long-lasting basis by the implementation of these austerity policies, which were a major source of job destruction, and the ongoing impact of these policies limited French companies’ ability to regain solid job momentum. The chart below shows a comparison of employment in the euro area and France and reveals that France suffered greater inertia and a weaker ability to adapt: changes in labor law can therefore act on this area.

The decrees to change labor legislation were presented at a press conference by Prime Minister Edouard Philippe, and Labor Minister Muriel Pénicaud.

We can make four observations.

The first point involves the decentralization of labor negotiations. During the presentation, the focus was on small and very small companies, but I think that the issue at hand is more far-reaching. The French economy is operating against a backdrop of major technological change, while international competition is much tougher than in the past, so each company must be able to adapt its organization and production methods in a more customized way. There is sometimes little, if any, similarity between a start-up and a large industrial or services company, so it seems important to be able to adjust the rules differently for the different types of company. This would help improve companies’ ability to react on jobs. Implementing decrees will then need to ensure that negotiation is not too one-sided. However, this will be more effective than an excessively general agreement.

The second issue worth mentioning is the aim of setting rules for the long term, with a view to improving predictability and reducing uncertainty. In this respect, labor court standards that have been adopted are useful in reducing uncertainty and this will also be the case for all decisions taken if these choices are made with the long view in mind. If the decisions taken by the government are not subject to changes during the President’s term, this will at least cut back uncertainty for companies and be good news for jobs. Uncertainty is the enemy of employment.

The third remark is that this labor market reform is incomplete and one-sided. It takes a primarily employer-sided view, while not really improving workers’ rights, thereby making it one-sided. Meanwhile, it is incomplete as there is an urgent need to reform training programs so that companies’ improved ability to react to changes on the labor market does not become a source of uncertainty and concern for employees. Labor Minister Muriel Pénicaud mentioned this issue and Emmanuel Macron also discussed it in his interview with French news and political weekly Le Point. But the reform must be implemented, otherwise all the points outlined in the proposed decree will not have the desired effect…far from it!

The final point is that the question of work contracts has been ignored. Analyses of the French job market reveal the swift growth in fixed-term contracts, which are becoming ever shorter. This segment of the job market remains insecure and is used as a variable for adjustment. During the press conference Prime Minister Edouard Philippe indicated that there had been something of a toss-up between reforming labor legislation and reforming working contracts: the government has plumped for the first option. I do not think that the proposals from a number of French economists on implementing a single type of work contract are incompatible with this reform. I believe that maintaining the fixed-term contract/permanent contract split means keeping a whole fringe of insecure jobs on the labor market, in a trend that we are witnessing across all developed countries. Each country has its own system, but this is a source of adjustment that is now accepted with the aim of making the job market more flexible.

It is a shame that the government went down this route on fixed-term job contracts, as this type of contract is very prevalent among young workers. In his interview with Le Point, the President argued that younger people and those with low qualifications deserved a particular focus. Training will help solve some of the problems that these two groups encounter, but the questions of stability and insecurity still remain to be dealt with at a later date, which is a great shame.

This is the translation of my weekly column for Forbes. You can read it here

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog