After just one year it is still too soon to make a full assessment of the Macron presidency, so the question we must answer is whether the measures taken by his government over this first year are the rights one to tackle the changes we have witnessed worldwide.

In part 1 of this series, I outlined the need to make growth more self-sustaining, even in a context of ongoing globalization. I described the need to raise the innovation aspect in our investment, and the necessity of making the labor market more adaptable to better address change. Recent research by Gilbert Cette et al uses a broad international comparison to suggest that high employment protection legislation in France leads to capital-to-labor substitution. This would explain high investment levels in France. However, the authors note that the innovation component of this investment is inadequate and does not sufficiently bolster productivity. Another conclusion of the report is that a more flexible labor market means higher quality capital.

And this equation lies at the very core of the supply question in France: capital needs to be more efficient, while the labor market needs to be more flexible in its ability to adapt. I noted in part 1 that steps taken to support public investment along with government labor market decrees help ease these restrictions and promote an adjustment in supply.

But we have seen two other watersheds in the world economy that the French economy must now address if it is to further integrate i.e. the location of production and the location of innovation.

The second shift is the geographical location of production.

The center of gravity has shifted across to Asia during the post-crisis years, as these counties have fostered astounding industrial and manufacturing momentum, going from merely assembling to managing the entire process from design to production, where quality has swiftly and efficiently improved. Programs launched in China in particular, such as “Made in China 2025”, aim to further drive this trend and bolster both quantity and quality. One of the key aspects of the Chinese program is to create disruptive innovation that will spur on industrial performances. This will give China and Asia additional headway and is one of the reasons behind Trump’s trade measures against China.

Why this short development?

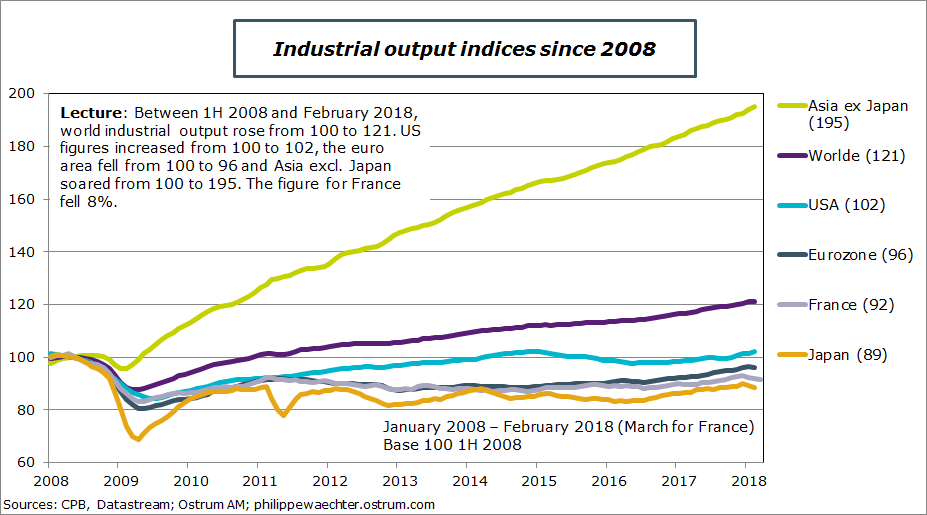

The three big geographical areas that fuelled the world economy’s growth since the Second World War have been pushed aside by Asia over the past ten years. The chart below is an impressive illustration of industrial output since before the 2008 crisis, showing that in February 2018, i.e. in just ten years, these three major areas have at very best maintained their output on a par with the start of the period. On average, the three main countries that drove world growth in the postwar period have made zero contribution to growth in world industrial activity in the past ten years, and this marks a real watershed.

The 2% rise over 10 years in the US is lackluster, up from 100 to 102, while production in the euro area shed 4% and in Japan the figure fell 11%. The famous Industry 4.0 that everyone is talking about is happening on distant shores, far from the major developed countries. A breakdown of the euro area’s performances shows that France is down 8% and Germany up only 5%.

However, Asia excluding Japan displays a score of 195, revealing a remarkable contrast.

This jump in industrial output across emerging markets, particularly in Asia, means a swiftly declining weighting for France as a proportion of the world economy. France accounted for 4.4% of world GDP in 1980 (in purchasing power parity, as measured by the IMF), while in 2017 the figure stood at a mere 2.2%. This is not exclusive to France as Germany’s showing dropped from 6.5% over 3.3% over the same period and the euro area from 1999 to 2017 saw its share decline more than 6 points and now accounts for only 12% of world GDP. The euro area is declining in relative terms as Asia is developing very swiftly.

Faced with these challenges, Emmanuel Macron has taken a very decisive stance on Europe and the need for its countries to join forces.

In his September 26 speech at the Sorbonne, the French President highlighted that Europe remains vital to France, on the one hand offering the country a presence on the worldwide stage and on the other safeguarding the advantages that European integration has already provided for all its citizens. Meanwhile in his Frankfurt speech on October 10, he reiterated the importance of culture in Europe and underlined France’s solid ties with Germany.

In our globalized world, Emmanuel Macron’s challenge will be to set the stage for Europe to have greater scope to decide its own future and generate more self-sustaining impetus, which is also the vision he outlines for France, which I mention in part 1.

The French President’s approach is primarily political, as he believes that political choices need to be made to resolve the questions facing European citizens today.

There is an element of this in his Sorbonne speech. He notes that a number of issues must be addressed Europe-wide if they are to be effective, such as energy transition, the fight against terrorism, the refugee crisis, and many more. Taking a joint approach on these issues would lead to greater consistency within Europe and also make the bloc’s position clear for the rest of the world, making for a more united front and commanding more attention from our partners across the world.

This throws up a hefty political challenge as each government must get its citizens onboard to address broad-based issues that extend far beyond national borders.

From an economic standpoint, there is also the overarching idea of encouraging shared and more self-sustaining impetus. A joint budget much higher than current figures is needed if we are to see greater consistency in the choices made across the continent. This budget must also have a countercyclical dimension with greater involvement in economic management for each individual country, and this raises the possibility of a more federal approach, automatically leading to a different balance of power between Europe and the Member States, as in any federal state.

But Europe is not united behind this idea of a joint approach.

Some countries, particularly in the north of Europe, think that each government should remain in charge of its own fiscal policy and manage its economy as it sees fit, with no desire for ever greater union.

Germany takes a second approach, which involves promoting any factors that will allow for internal adjustment in the euro area, particularly banking union.

Meanwhile, France adopts a third way, with Macron seeking a political approach and an extra measure of commitment from each country before overhauling European institutions. Political choices require a long-term commitment as they often involve transferring sovereignty. The other institutions (Banking Union for example) can then develop without too many uncertainties.

So the citizens of Europe must choose between these three very different approaches to Europe and European integration. The Council of Europe on June 28 and 29 could be an excellent opportunity for this. These choices will be much-awaited in light of current uncertainties on the path Europe will take, with the road taken by Italy remaining a particular cause for concern.

I believe that the French President’s more political approach is the most sensible strategy in light of the new world order I outlined in the introduction. It is not enough to simply produce, it is also vital to influence decisions taken elsewhere, and politics is the only way to achieve this.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog