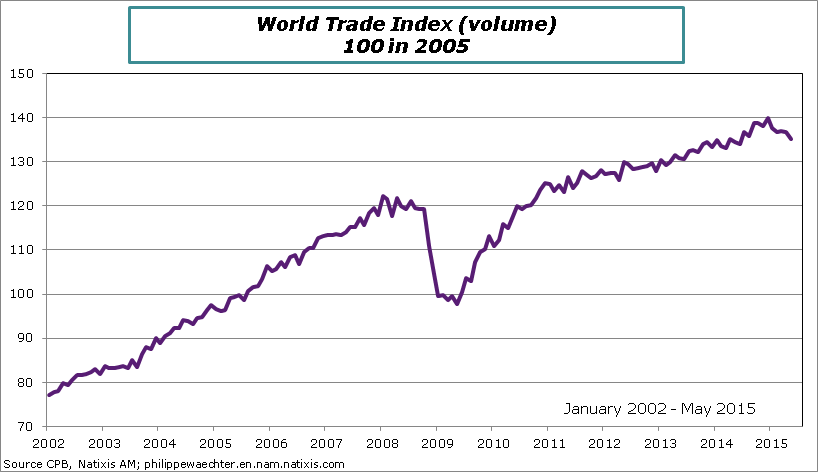

In a recent post, I was worried by the weak trend seen on world trade since 2011 and on its recent decline. It is down by 8% (annual rate) between December 2014 and May 2015.

The absence of a rebound reflects a series of negative shocks on the global economy that have limited the possibility of a global recovery.

Before trying to understand these issues, it’s interesting to look at the graph of world trade; not in yearly change but in level. We can see that since the beginning of 2002 there were three periods

• From 2002 to 2008 the momentum of trade was high consistent with the 7% growth seen in the first chart of my previous post. I started in 2002 as Chine became membership of the World Trade Organization in December 2001.

• The second phase is the break and the recovery in 2008 and 2009. The catch-up was rapid but not complete: the index has not converged to its pre-crisis trend. We can do that formally but we see on the graph that world trade momentum remains far from the 2002-2008 trend.

• After summer 2011, the dynamics is low and the slope is weak, much weaker than what was seen before the crisis. Since the beginning of 2015, world trade momentum has plunged.

Here is the situation

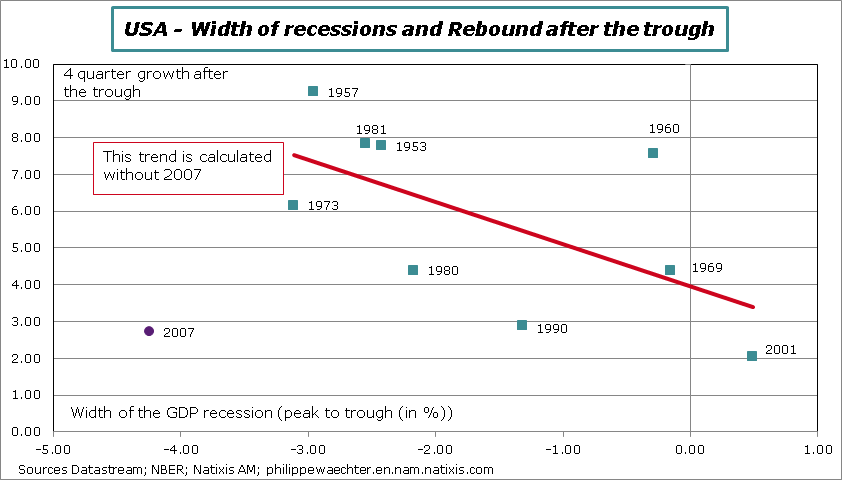

• During the recovery period, the US economy has not had its usual behavior. In the past, the recovery after a recession was strong, helping the economy to converge to a high trajectory.

The graph below shows that the rebound after the crisis has been particularly weak compared to what was seen since WWII. This was a point that was perceived in the chart of the annex of my previous post. We have here a clearer view. The chart presents the width of every recession since WWII (the width is measured as the change of GDP from the peak to the trough of the cycle according to the NBER). This measure is on the horizontal axis. On the vertical axis is the GDP growth from the trough to one year later. On the graph, dates are associated with the peak of the cycle (more precision on dating here).

I have added a trend (in red) that is calculated with data of all recessions except 2007. We see that 2007 is far from this trend. Would the recovery be on the trend, then GDP growth in the year after Q2 2009 would have been 9% and not the mere 2.7% observed.

The US economy has not been able to converge to a high trajectory and to push up the world economy on a higher profile (as it did in the past). This reflects the fact that the crisis was located in the US. The accumulation of private debt and the fragility of the banking sector have weakened the recovery, limiting the capacity of the US economy to converge to a higher trajectory.

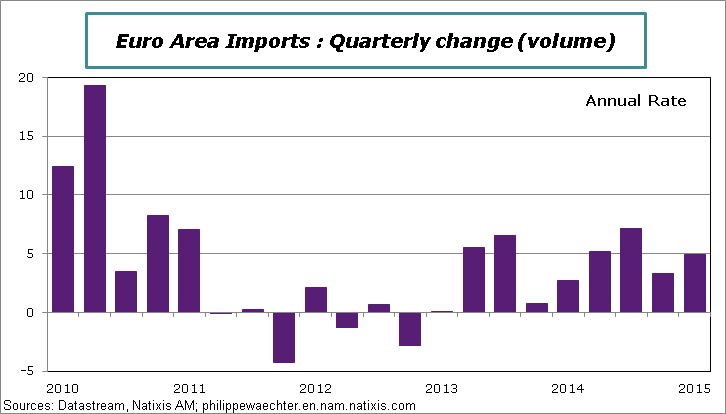

Austerity policies have weakened internal demand (this latter was not strong at this moment of the cycle), leading to a long and deep recession. As policies wanted to rebalance external account for a large number of countries, imports have fallen down dramatically. The Euro Area was not an engine for the world trade recovery. It has probably be one important source of its fragility.

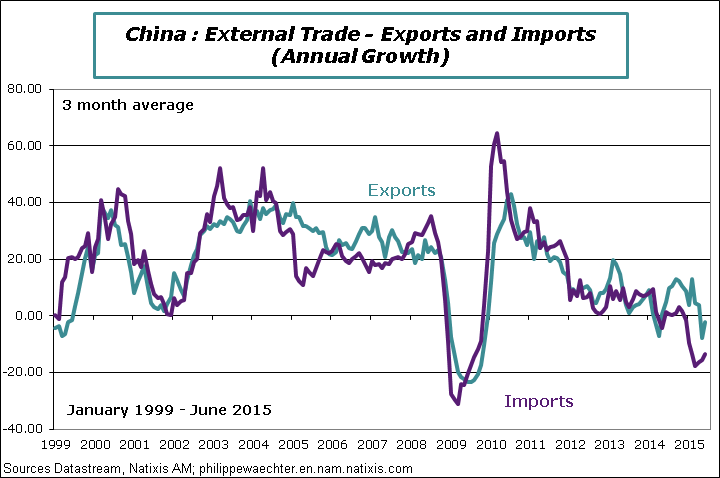

The Chinese external trade that was really strong before the crisis has emerged after 2011 with a weaker profile. Exports and imports changes that were between 20 to 40% before the crisis are now close to 0%. Its impulse on world trade is now clearer reduced.

None of these three has the capacity to grow way above its potential trajectory in order to converge to a higher profile and to pull up the rest of the world.

The question then is to know if a change can be expected in a foreseeable future. In other words, among the three blocks, can we expect a rapid recovery that could create a persistent positive shock that could spill over the rest of the world?

Spontaneously the probability is low

The US economy momentum is currently low as it was shown in the last graph of my previous post. Adding the number for the second quarter of 2015 doesn’t change the picture (the picture is in fact weaker as average growth since Q2 2009 has been revised down from 2.2% to 2.1%).

Can we expect a rapid and brutal change in the GDP profile when the unemployment rate is already at 5.3%? OK this rate can go down but usually the rapid improvement in GDP is associated with a plunge of the unemployment rate after the end of the recession. We haven’t seen that in the current cycle.

In a recent paper Barnichon and Figura question the profile of the participation rate. Usually the improvement of the economic activity leads to a higher participation rate implying a temporary boost in unemployment rate. It creates then a persistent support for higher growth. This is not the case in the current business cycle. In their paper they say that incentives to work have been reduced. They explain the change in incentives by the 1993 Earned Income Tax Credit and by the 1996 reform of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children. Both have reduced incentives to work especially for families with low-income and children. In the short run, if the law remains the same, there is no reason to imagine a higher participation rate and then to imagine a boost in economic activity. Moreover, as seen in the last Employment Cost Index for the second quarter (2% year on year), the rise in wages remains limited.

In other words, an improvement can be expected but not a break that would create pressures on the GDP to durably jump above potential growth. Expecting a change on world trade coming from the USA is probably excessive.

In China, the two attempts to boost growth through financial means have failed. Higher indebtedness for State Owned Enterprises has created stronger imbalances and a situation at risk for regional banks (see here in French). The bubble on the equity market has burst last June and will not drive expansion (see here). The economy is trying to find a new path based on its internal momentum. It needs a reallocation of resources that can, in the short-run, be costly in term of growth.

The Chinese economy, with now a large middle class, must converge to a more internal, service oriented growth. The rebalancing of growth has started in 2011 and takes time. This means that its GDP trend will be lower and will not be a boost for world trade.

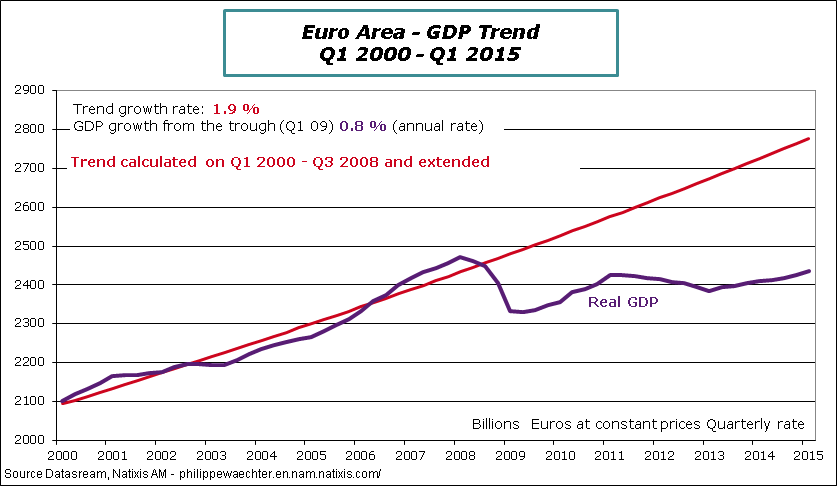

In the Euro Area, there is a rebound in growth but its magnitude at a 2 to 3 years horizon is just above 2%. To go further, there is a need for a strong internal demand associated with deep reduction in internal balances (large German external surplus). This is not the case currently even if internal demand is stronger than in recent years. The current scenario is not strong enough to boost world trade.

This perception of the global economy is highlighted by the recent discussion on secular stagnation between Larry Summers and Ben Bernanke.

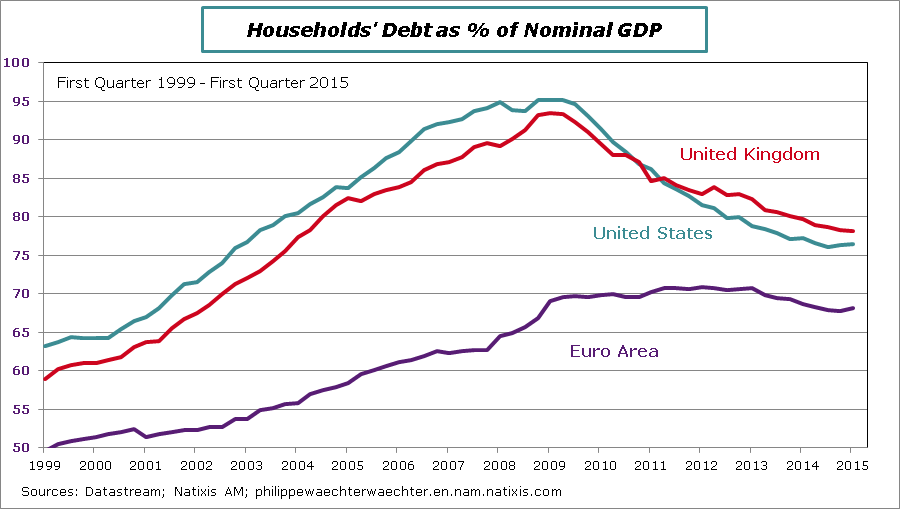

Larry Summers explains that excess from the past has been largely driven by private (households) indebtedness. This situation is not back to a balanced situation as debt is still very high as it can be seen on the graph below. Associated with ageing population, this could imply a weak internal demand leading to reduced investment opportunities. The GDP growth trend would be lower than what was seen in the past and would be associated with low inflation rates in western countries. In that environment, economic policies must remain accommodative and central banks’ interest rates close to 0%.

Ben Bernanke suggests that there will be investment opportunities linked to the current strong momentum in innovations. For Bernanke this will create a more virtuous framework than what Larry Summers has in mind. Therefore, the economy could converge to a more normal and balanced path. Inflation trend would in that case be closer to central banks’ target and monetary policies would not be condemned to be accommodative.

But to paraphrase Robert Solow, innovations (and robots) are everywhere except in growth and in productivity figures. I’m sure that the impact will be strong but it will be perceived only at a mid-term horizon. (see here a discussion on the impact of innovations)