In last week’s column (see here), I discussed the importance of public debt as an asset that enables wealth to be transferred to a date in the future, while restricting risk, along with its ability to effectively absorb economic shocks. I also noted that I was less concerned about public debt than private debt, particularly household debt.

The major difference between public debt and household debt is that a credible State issuer can issue debt with sometimes very long maturities, which households cannot do, so they do not have the same flexibility to adapt to shocks.

The other key point is that a State enjoys the advantage of being able to raise taxes, and this option of being able to potentially increase tax is reflected in investors’ confidence in sovereign issuers on the financial markets. When a State is seen as being unable to raise taxes, then its credit collapses and its ability to issue securities disappears. On developed markets, we can observe that the likelihood of a crisis related to public debt is therefore low.

However, it is a different kettle of fish for households, for two reasons. The first is that a household exists for a finite period of time and it cannot carry over its debt the way a State does. Public debt is never paid down, while household debt has to be paid off at some point.

The other difference is that the accumulation of household debt is based on the acquisition of an asset, usually a real estate property. The household’s ability to increase its debt is based on this asset’s capacity (which the debt is financing) to satisfactorily maintain its value. During the subprime crisis, we saw that this mechanism can grind to a halt when real estate property loses value.

In the event of a crisis, the only solution is to liquidate the asset, which triggers a watershed.

This is where the State played a key role after the subprime crisis, injecting public debt in order to absorb the shock and taking over from private debt, which could no longer be issued.

I mention the household debt issue for two reasons.

The first is that this type of debt increased considerably in the first decade of this century. Workers’ weak income growth was partly offset by the option of resorting to greater debt. Household debt can also be a reflection of an economic system that is no longer operating efficiently and we see this situation in the US and elsewhere.

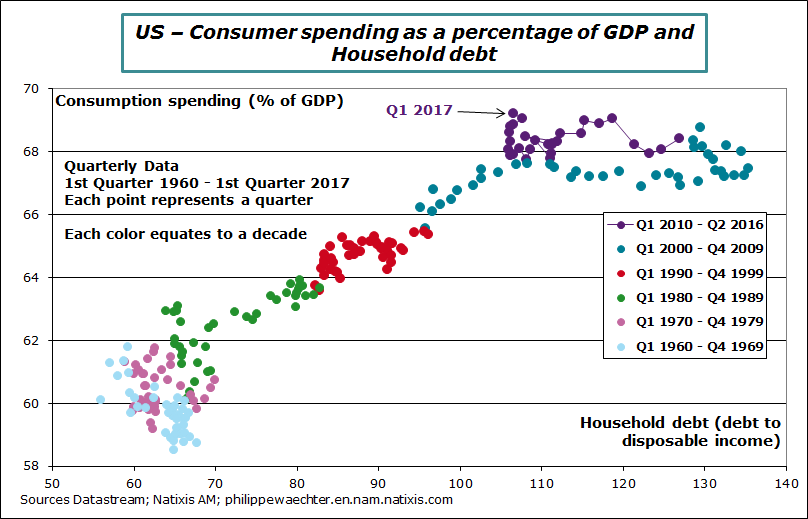

The chart below shows the example of the US, with household debt rates on the horizontal axis and consumer spending as a percentage of GDP on the vertical axis.

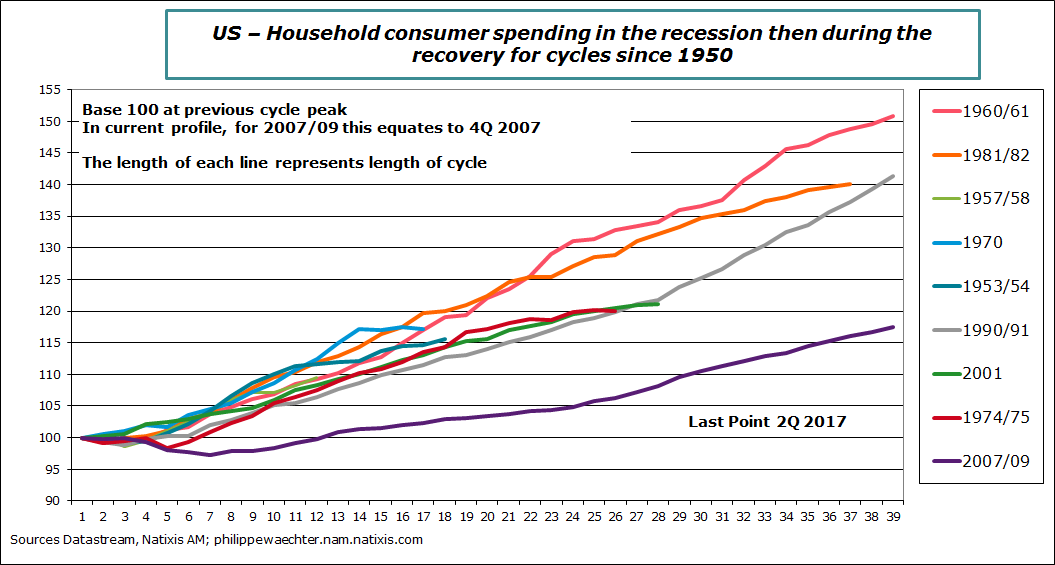

We can identify several phases. In the 1960s, 1970s and up to the middle of the 1980s, there was no relationship between consumer spending and debt, but this situation changed during the mid-1980s as households took on debt in order to spend more. In the 2000s, they then took on debt to be able to continue spending in the same way. Debt has fallen since the financial crisis, consumer spending as a percentage of GDP has stabilized but growth in household spending is much slower than during previous economic cycles, as shown by the second chart.

Excessive household debt then leads to a decrease in consumer spending against a backdrop where income is not increasing quickly (problem of insufficient productivity gains but this is not specific to America).

This relationship between debt and consumer spending emerged at the same time as the imbalance in income distribution materialized in the US, as greater divergences appeared in the distribution of income. In the 1960s and 1970s, productivity gains drove wage income, then in the mid-1980s, median wages began to grow much more slowly and households were forced to get into debt to maintain their spending. This trend is not very efficient in the long term, as shown by the current situation.

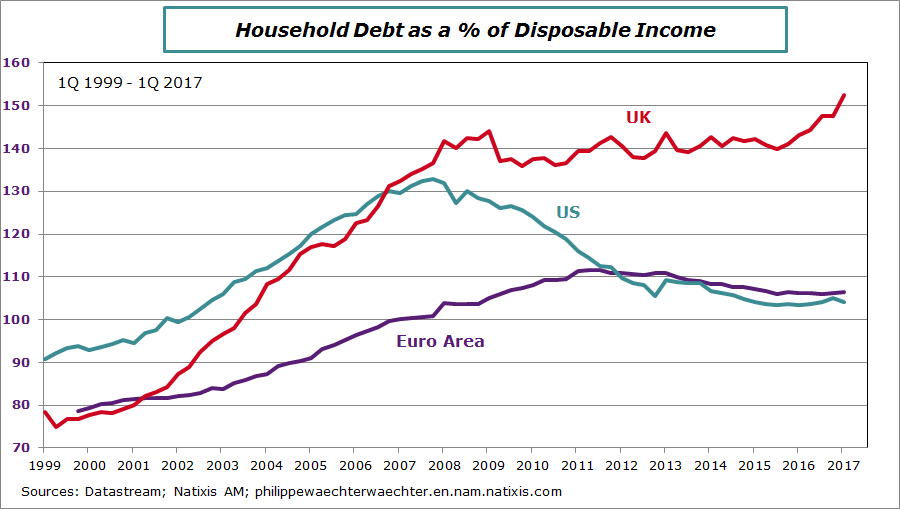

The other reason is that household debt underpinned the surge in the real estate market before the crisis in 2007/2008. The accumulation in debt had led to an increase in real estate prices, which turned out to be unsustainable in the medium term. The problem today is that household debt has not really decreased in the euro area and it is rising swiftly in the UK due to both the increase in nominal debt and also the fast drop in disposable income. Meanwhile, in the US, household debt is down.

Generally speaking, households’ high debt restricts their leeway to adapt as income momentum remains limited across the board. It is therefore important and necessary to generate substantial productivity gains to be able to distribute sufficient income to limit household debt overall.

Household debt reflects households’ ability to increase their resources via the acquisition of a durable good, but when this amassing of debt is not built on a well-valued underlying asset, then economic momentum is hampered. This is when public debt can take over to help smooth out adjustments over time and thereby avoid drastic shifts that dent both jobs and income.

This is the translated version of my weekly column for Forbes. You can read it here in French

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog