The answer is yes…or at least that was the answer from Mario Draghi at the press conference after the September 7 monetary policy meeting, thereby indicating the importance of pursuing monetary accommodation in order to keep on supporting economic activity, despite the recent uptick in growth. However, the economy is failing to get back on the road to higher inflation and this means there is still an imbalance.

More broadly speaking, I think that the world economy is still in crisis, especially in the west, if we define a crisis as a transition period between two stable trends.

I don’t mean a financial crisis as triggered by excessive debt used to finance the acquisition of property: financial crises like the one in 2007/2008 are as old as time itself.

Beyond this financial aspect, we can identify two major sources of imbalance, which persist and keep the global economy stuck in a crisis.

Technological imbalance

The first mismatch is technological. The global economy is enjoying a phase of soaring innovation but yet suffers low productivity gains. This situation is far from inconsequential as Schumpeter taught us that a long economic cycle gets off to a start during phases of innovation on the back of strong productivity gains. Despite the impressive innovations that we are now witnessing from time to time, this long cycle is taking quite some time to materialize and productivity gains remain low (productivity gains are the surplus created by the production process: the higher they are, the higher real income can be).

In this respect, we can look back and draw something of a parallel with the period when electricity arrived in western countries. The revolution at that time was not that electricity replaced coal, but rather that an entirely new production process including electricity came into being. This is why it took a long time for the full effects of the arrival of electricity to filter through, and why productivity gains took a long time to emerge.

We are probably witnessing a similar process today. Recent research shows that weak productivity gains are particularly attributable to a severe imbalance in the distribution of innovation: we see big companies display hefty productivity gains as they reap the benefits of rising yields, while smaller companies suffer weaker yield and do not take on board innovation with the same speed and efficiency as their heavyweight counterparts. This two-tier development means sluggish average growth in productivity gains overall, yet all the while new innovations are emerging at high speed. This indicates that the production process has not yet been remodeled to factor in this spectacular technological progress across the board.

We are in the midst of a period of transition that may last for quite some time, but can vary from one country to another, although it is does not seem to differ much if we analyze the situation from a productivity gain standpoint.

Imbalance as our world grows bigger

The second source of imbalance is that our world is getting bigger. Twenty years ago, world growth was limited to the west, driven by the US, Japan and Europe. There may have been potential emerging markets in the making, but they never quite made it. This was the case for Brazil and Iran for a long time during the 1970s, and there were sometimes periods of instability when oil price rises stepped up a gear for example. But this was all only temporary.

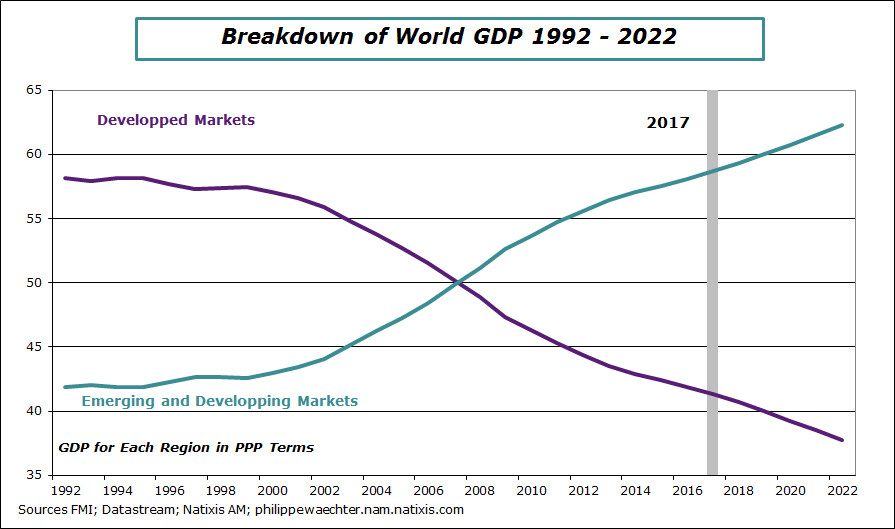

The world no longer works this way and emerging markets now have a major role to play in world growth momentum. We can see on the chart below that the situation has well and truly changed since the 1990s when China did not have such an extensive role. The country has carved out its very own robust momentum largely, although not exclusively, as a result of its size, and a large number of emerging markets have benefited from this.

There was a huge change in the context for developed markets, due to a deep and lasting shift in the dynamics of competition. This new situation is not yet set in stone as China’s growth is not yet domestically self-sustaining i.e. whereby growth becomes much more reliant on domestic demand than it is at this stage. Developed countries have seen their economic and political power dwindle over the past two decades without being able to do much about it, particularly as productivity gains have been weak over the past ten years and do not leave much room for manoeuver.

The crisis in western markets is where these two transitional phases overlap: the technological with the geographical, and this leads to tough times for developed countries as nothing seems to work the way it did before. There can be a severe temptation to resort to populism to try to hide from these problems that are impossible to control. Donald Trump’s election and Europe’s recent toying with populism reflect the appeal of this insular approach and the excesses that go with it. In this respect, Europe has fared well so far.

_________________________________________________________________________

This is the translation of my weekly column for Forbes (read it in French here)

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog