The US administration’s partial shutdown marks a first in the country’s history: this is the first time that we have witnessed this type of situation when the same party occupies both the White House and Congress. It was somewhat different during Barack Obama’s presidency in 2013, as Congress was not in Democrat hands, and looking further back, President Jimmy Carter came up against difficulties in financing his budget with his Democrat majority at the end of the 1970s, but there was no shutdown.

This failure for President Trump and Congress to get along has been the hallmark of the current Republican administration’s first year. The power dynamics between the two institutions ends up creating a puzzling sort of inefficiency. The disagreement of the moment is on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which involves young foreign-born individuals who arrived in the US as children. It turns out that Trump is in favor of a law to welcome them in the end, but the Republicans are unhappy with a bill partly drafted with Democrat agreement. This is a power struggle and not a cooperative political relationship between the President and Congress.

We had already witnessed this dysfunctional situation during attempts to repeal Obamacare, when Congress rejected Trump’s proposals.

It is only during the vote on the tax reform bill that the tougher conditions for Obamacare eligibility finally wipe out healthcare availability for 13 million Americans. The healthcare program set up by the former president still exists but eligibility conditions are tougher, hampering the country’s poorest.

Beyond the partial and temporary shutdown of the US administration, it is worth making a number of remarks on the Trump administration’s first year as a whole.

– The first is a radical change in communication. Specialists on the US economy and society along with many others must now pay particular attention to tweets from the White House as they can provide information on new policies for economy strategy, US diplomacy and any number of other issues.

– The second change is the new non-cooperative international politics coming out of Washington, even with close and friendly countries e.g. Mexico, Japan, the UK and even Germany.

This makes international relations bumpy as America is no longer the mainstay around which other countries can unite, but rather a country that does not even try to rally up its usual partners. A new, as yet unclear, balance is emerging for the western world. This can provide Europe with an opportunity to carve out a special role for itself – it is up to Europeans to grab this opportunity.

The Trump administration’s approach also includes muted but very real tensions with China. Last Friday’s publication of a report casting doubt over the advisability of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001 reflects this suspicious mood. These tensions prompted China to retaliate that it would cut back its US Treasury purchases in the months ahead, triggering the recent decline in the greenback and the rise on the US 10-year bond yield.

The China/US relationship will be the focus of concerns in 2018, as it could throw world growth momentum off kilter and strike at the current robust pace of world trade, which would be disastrous.

Trump’s economic model is a zero-sum game: other countries’ gain is the US’s loss. These dynamics must be reversed. It is this very approach that explains pressure from Donald Trump at the start of his term to repatriate manufacturing jobs to the US.

And it is this type of approach that explains the tax reform: tax paid by Apple and other companies in the US will not be paid in other countries. This will contribute to weakening other economies, particularly in Europe as business for these large groups has no tax counterpart, and this will dent all European citizens.

US politics is something of a muddle, with a surge in identity politics (on migrants and the dreamers) and morality (support for the anti-abortion movement), yet it obeys no moral standards when it favors higher earners over the lower paid portion of the population.

There is no reason to think that 2018 will see a change in this unusual modus operandi, although we should keep an eye out for fresh surprises that could come from the US’s relationship with the rest of the world.

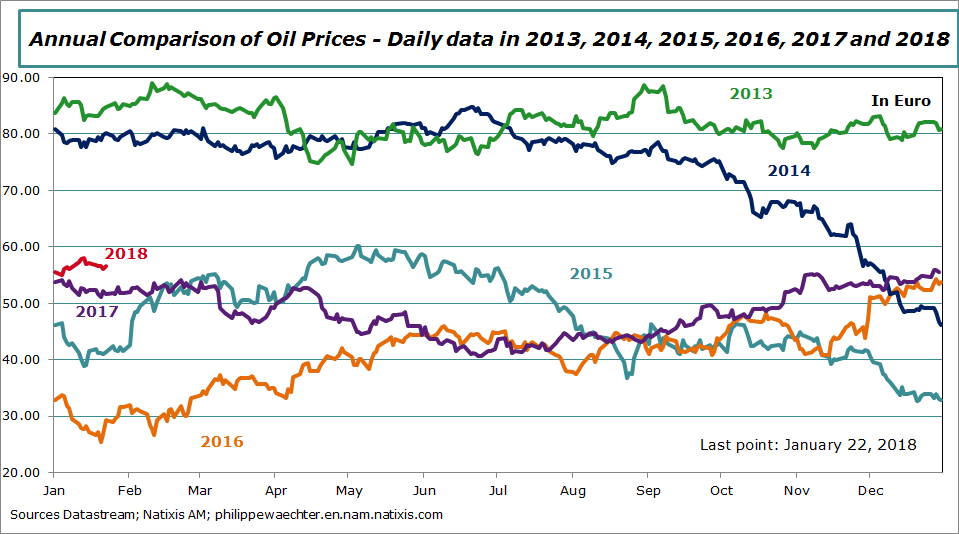

The other point worth noting is high oil prices, now standing at USD70 per barrel.

The chart shows that prices are currently well above figures at the same time last year and we can also see that if they remain at this level, they will be systematically higher than figures in 2017. This would push up inflation. The contribution from energy will be higher, probably around 0.4-0.6% in the Spring vs. 0.3% currently.

The main factor driving up oil prices is robust demand. When supply was high in 2015-2016, there was downward pressure on prices as demand was not very strong. Inventories built up and the agreement between Saudi Arabia and other producers was not effective. During this phase of lower revenues, each producer is tempted to produce that little bit extra in order to improve revenues: this keeps a lid on prices.

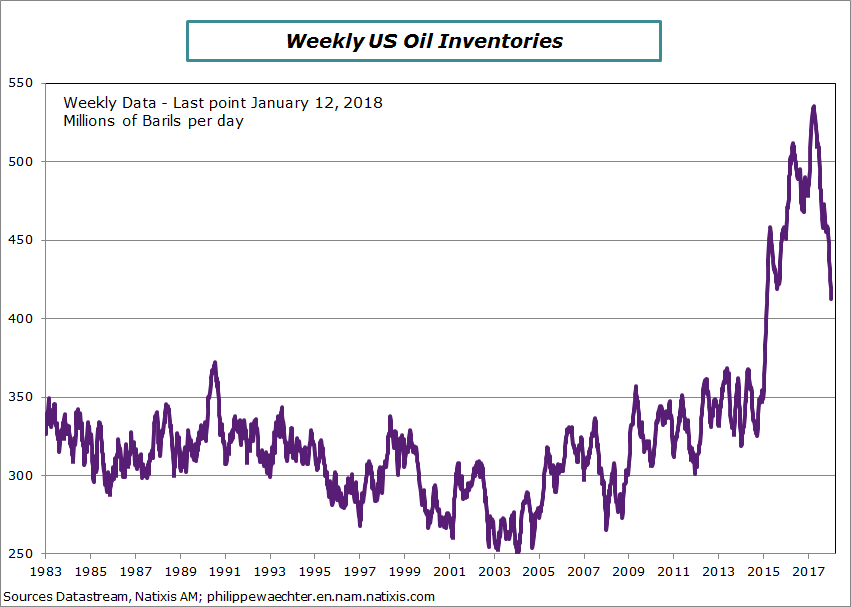

However, when demand improves, revenue projections are more robust and the temptation to cheat or increase production is lower. This is the case for shale oil production in the US, which does not increase massively when prices are attractive: this keeps prices high and inventories therefore fall in order to meet demand (see chart).

The acceleration in demand reflects the improvement in the economic outlook and this is set to last for quite a while. So a new equilibrium point must be found as the $50/bbl point is no longer feasible. Let’s say $70.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog