Growth has made a comeback but each country already wants to take its own path. Unity is no longer on the cards and the world economy is fast going down a very different road.

During the recovery in 2016 and 2017, the worldwide situation was relatively stable, with no major imbalances, and the central banks cut some slack when required to make it through any bumpy patches. This approach worked fairly well as the pace across the various areas of the world became more uniform, driving growth and trade momentum, and economists were constantly forced to upgrade their forecasts.

But those days are gone, and this cooperative and coordinated dimension has disappeared.

In Europe, Emmanuel Macron now seems to be the only one championing the reform of European institutions to ensure they last. The German Chancellor had to wait for the end to consultation with the SPD to see if she would be able to form a new government, so the German government is no longer in control. Concerns over the AfD’s gains in the polls were fully justified as it is now the leading opposition party.

Meanwhile in Italy, populist parties won more than 50% of votes in the March 4 elections and doubts are increasingly rife as to whether a government with a strong European slant can be formed.

Questions over Poland’s and Hungary’s intention to remain fully-fledged EU members are also weakening Europe’s institutions.

So growth is back in Europe, but the area’s political foundations are shaky and we can justifiably be concerned about what will happen if growth slows and job creation becomes more sluggish: the political balance could well be disrupted.

Looking to China, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) sets out a roadmap for trade with third countries and reflects the country’s desire to shape its trade initiatives as it sees fit in order to limit the risks on its own situation. The logic underpinning this program is not necessarily entirely compatible with the WTO’s approach.

This whole issue is particularly important in light of the United States’ recent decision to implement import duties on steel and aluminum, with the risk of knock-on effects worldwide and the danger of fresh imbalances across the globe, especially in Europe which is the primary supplier of US steel imports. The new aspect in the current situation is that the US is now targeting countries traditionally seen as partners, so the logic behind these moves is problematic.

These measures will probably lead to an increase in US steel and aluminum production as production facilities in the country are not running on full capacity, and foreign production will be more expensive. This is actually one of Trump’s arguments: production facilities can run at higher capacity so imports should be restricted in order to promote local production. But it will not be enough to meet all US demand, and prices are poised to rise for downstream sectors in the US, while also leading to lower exports for Europe and pricing pressure for non-US steel and aluminum production, which will no longer be sold across the pond. This will dent these sectors in Europe.

This US initiative is also worrisome as it seems to be just one piece of the jigsaw rather than the whole picture. The While House even seems to want to take this strategy even further, apart from for countries that request special conditions and are willing to accept the terms laid out by Washington, which is probably not good news for these countries. This strategy sees the US break with WTO practices, on the grounds that it is supporting its local business interests. This policy will merely serve to further strengthen China’s trade programs.

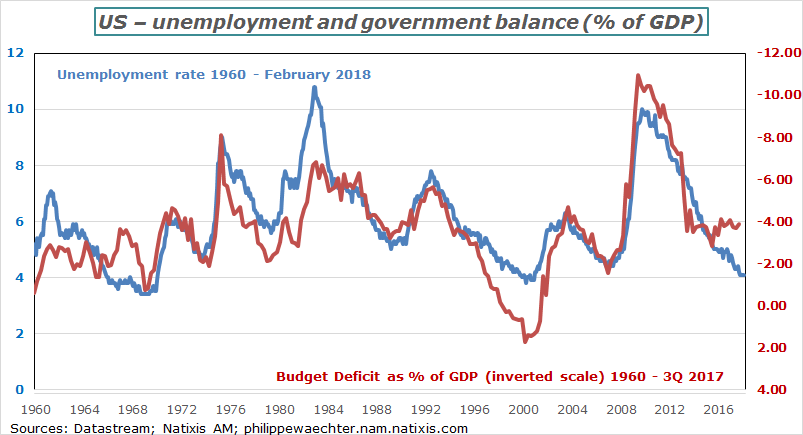

The other aspect of the current US strategy is that it pushes growth up via very aggressive fiscal policy, amidst an economy running on full employment. Generally speaking, when unemployment is very low, the US government’s deficit decreases, which is logical as the two indicators, unemployment and the public balance, provide a reflection of the overall business cycle. The usual regularity of the chart below is set to be disrupted in 2018 by moves from the White House and Congress. Unemployment is poised to remain low but the public deficit will increase, easily rising above 5% and moving towards 5.5% or even 6% and more.

The US is adopting inward-looking politics. When Reagan embarked on stimulus moves, the economy was far from full employment, unlike the situation today. So the aim of this approach is not macroeconomic, but rather a strategy to redistribute wealth towards the richest portion of the population, as shown by simulations for the 2018-2027 period, which is the initial duration of this fiscal policy.

This policy is set to shore up domestic demand and further accentuate the external trade imbalance, as already seen over recent months. Pressure will initially emerge on the US market, so we can expect increasing pressure on inflation.

To avoid the fall-out from this, the Fed will have to take faster and more decisive action than expected, which means that we can envisage more rate hikes in 2018 (at least four) if it is to curb the imbalances triggered by fiscal policy.

The US economy has not displayed robust growth across the current cycle (beginning in the second quarter of 2009), but this did not trigger long-term imbalances. Growth could have ambled along for quite some time, with monetary policy safeguarding a balance between the various aspects of the cycle, but the White House took a different route, creating a shock on fiscal policy along with a shock on trade via higher customs duties.

This is set to lead to higher interest rates from the Fed and a flattening yield curve, as investors will still want to believe in the Fed’s credibility and will not factor a long-term increase in inflation forecasts into long-term rates.

The other consequence is that the Fed will have to normalize monetary policy more quickly than expected, and in order to address this possibility, the ECB will not want to take the risk of informing the market when it will change its monetary strategy. Benoit Coeuré was clear on this point during his interview on French radio yesterday morning, and this reflects the ECB’s dwindling independence as its strategy now hinges on moves from the Fed.

The Fed’s strategy is set to push up the dollar over the months ahead, and the interest rate differential will end up having an impact, especially if the Fed has to step up the pace of rate hikes.

Rate hikes will be faster and sharper than expected, so volatility will surge on the equity markets. There is always an 18-24-month lag between the Fed’s rate hike and the increase in volatility, so this will take us to 2019/2020.

The three large geographical areas are no longer taking a coordinated and cooperative approach. The US and China want to set their own rules for international trade, with the danger that they will move away from WTO rules and resume a bilateral strategy all round, which will not be fair for parties across the board. Meanwhile in Europe, the lack of political initiatives raises a lot of questions. Economists put forward solutions but these are just castles in the air if they do not have political support.

So the momentum triggered by the recovery has now come to an end and the emergence of a new political order is leading to uncertainty on the world economy’s ability to sustain the pace of growth achieved in 2017 and 2018 so far. The crisis is not over as the political transformation is not complete.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog