Co-authored with Zouhoure Bousbih

The dollar has been gaining ground since mid-April, with investor perception that the Fed would take stronger and swifter action than expected, and this raises a number of difficulties for emerging markets.

The greenback’s surge against all other currencies is a game changer for emerging countries for at least three reasons: expectations of a swift rate hike from the Fed generally trigger capital outflows from emerging countries, which is what we are currently witnessing; the situation also hampers economic prospects due to insufficient liquidity and the ensuing rise in interest rates; these factors combine to further push the currency down and thereby increase the cost of paying off dollar-denominated debt (read my posts here and here to find out more about this deterioration).

This situation is particularly worrying when the current account balance (which reflects a country’s external relationships) displays a deficit, as the flipside to this is high external debt and a situation that is set to deteriorate even faster than elsewhere. This raises the question of financing the current account at a time when the country is suffering capital outflows, and the country in question generally has to up its interest rates considerably, pushing its economy into a downward spiral and ultimately locking it into a crisis.

We have witnessed this situation recently in Argentina, Turkey, Indonesia, South Africa and some other countries, and there is nothing unusual about it, but it is very a costly experience for countries hit by this adjustment.

At this juncture, I feel it is interesting to identify the mechanisms involved in this type of crisis by taking the example of Turkey. The country is currently undergoing this type of adjustment in a very dramatic way and the situation is made even more complex by the prospect of early presidential elections on June 24.

The Turkish crisis

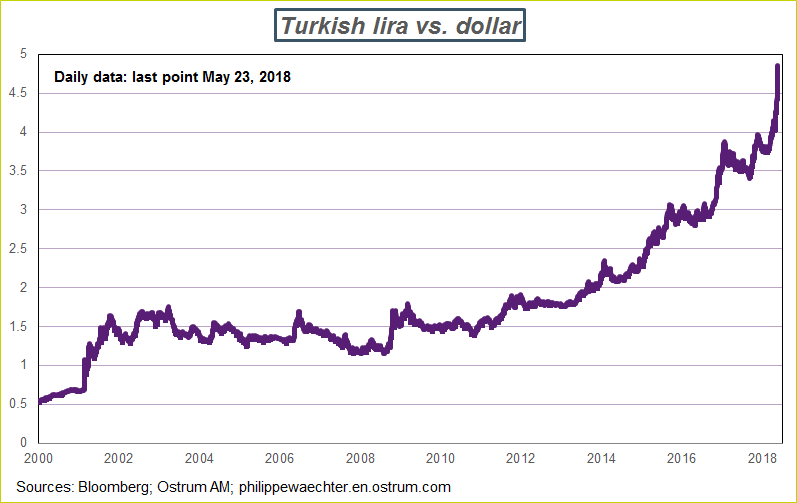

Among all the emerging currencies, the Turkish lira has been the hardest hit (apart from the Argentinian peso) by the sell-off that has dragged down emerging markets since mid-April following the dollar’s gains.

The Turkish lira has shed 19% vs. the greenback since the start of the year.

Yesterday on May 23, the Turkish central bank took a desperate step to hike its key interest rate by 300bps in order to curb the currency’s freefall after it hit a fresh record low against the dollar. This move stabilized the lira, which is now trading at 4.76 after a low at 4.90 and a high of 4.54 during the night after the central bank’s intervention, but this merely marks a stabilization not a turnaround.

Why is Turkey more affected by this sell-off than other emergings?

Turkey is extremely vulnerable from both domestic and external standpoints.

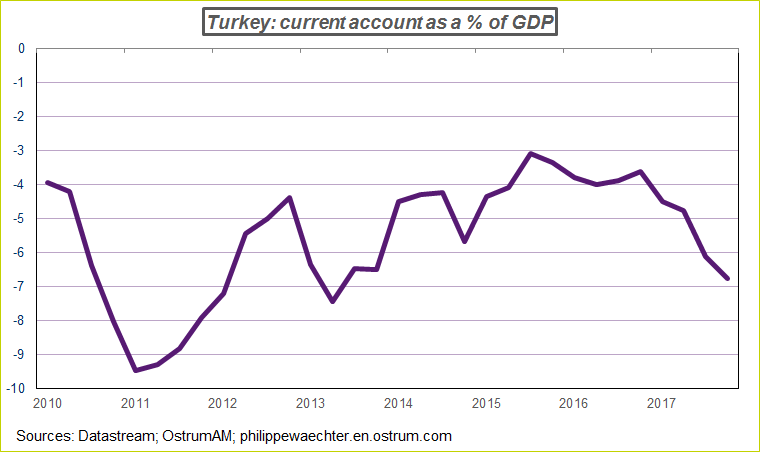

The country has a hefty current account deficit of more than 5% of GDP, which reflects its high external funding requirements. This lays the Turkish lira wide open to the effects of any increase in risk aversion, which would lead to sudden and severe capital outflows and threaten the country’s macroeconomic and financial stability.

This deep current account deficit can be attributed to Turkey’s high energy dependency. The country is a net oil importer, so rising oil prices push up the commodity’s import costs, thereby further worsening the current account deficit.

The Turkish economy is also characterized by low savings rates, which means that the Turkish economy grows fast and must be financed by foreign capital, yet the problem here is that this foreign capital is short-term and speculative, and if the central bank wants to hang onto it, it has no option but to keep interest rates high.

High budget deficit. Erdogan’s government has worsened the deficit with its increased public spending in an attempt to win the presidential and parliamentary elections coming up in June.

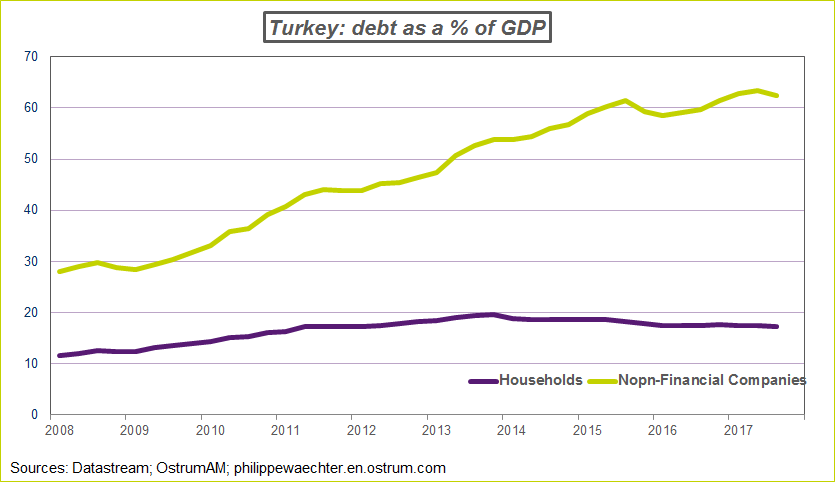

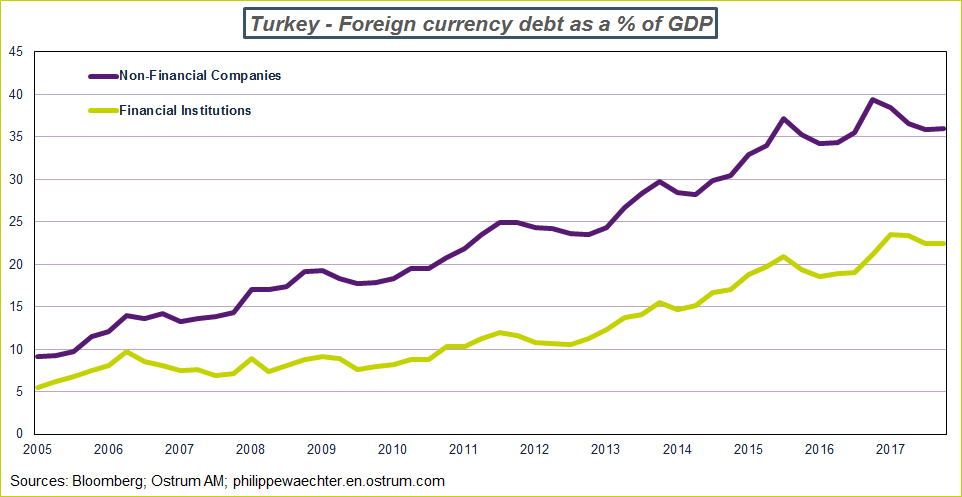

Debt is high and is particularly excessive for non-financial companies at 63% of GDP. Growth in Turkey has been driven by expanding loans and companies have taken on severe debt, particularly foreign currency-denominated (40% of GDP) and this makes them vulnerable to changes in the Turkish lira’s exchange rate, especially to the dollar.

Inflation is persistent and high, standing at 10.9%, and this can be attributed to expansionary fiscal policy as well as the spillover from the lira’s severe depreciation during previous surges in volatility on the financial markets, which pushed up domestic prices.

We seem to be witnessing a vicious circle, with the Turkish lira’s depreciation pushing up expectations and inflation.

Why is the central bank still behind the curve and why can it not manage to combat inflation?

The Turkish central bank is controlled by Erdogan and he wants to keep interest rates low to buoy economic activity and win the election, despite the fact that inflation remains high and constantly well above the central bank’s 5% target.

Why are rate hikes not enough to curb the Turkish lira’s decline?

The Turkish central bank yesterday made a desperate move to hike its key interest rate by 300bps to 16.5% in an attempt to curtail the lira’s decline after it hit a record low against the dollar. But this move only managed to stabilize the currency. The Turkish central bank seems to have lost its credibility with international investors as they all think that Erdogan is setting the rules for monetary policy based on his own political agenda, not with the aim of addressing macroeconomic imbalances. This is very problematic for the future, as monetary policy was the only remaining available source of leeway.

Interest rate hikes alone are not enough to solve the country’s macroeconomic issues, and the Turkish economy must reduce its macroeconomic imbalances by implementing the necessary structural reforms.

So what will the outcome be for the Turkish economy?

Structural reforms must be made if the country is to achieve more sustainable growth in the mid to long term.

This change will come at a political price, but it is vital. Reforms should address issues such as raising competitiveness, bolstering savings rates in the country, as well as increasing investment in education and technology to boost exports of goods with greater value-added. These measures will make the Turkish lira less vulnerable to the vagaries of foreign capital.

Foreign currency-denominated debt must also be cut back, particularly for non-financial companies, where it stands at close to 40% of GDP. The double whammy of rising US interest rates and a stronger dollar is particularly damaging for the country’s financial stability. A stronger dollar increases the cost of USD-denominated debt servicing, hampering companies’ ability to pay down their debt and thereby threatening the banking and financial system.

Sitting back and doing nothing carries the risk that the country will continue to hurtle forward towards greater debt. But this looks difficult at this stage. In other words, without reform the Turkish economy is poised to see difficulties for a long time to come.

Could the lira’s decline influence the June election results?

Probably. President Erdogan called early presidential and parliamentary elections on April 18 to take place on June 24, 18 months before the slated date on November 3, 2019. What is the reason behind this move? Erdogan received a first wake-up call in 2015 when he lost his parliamentary majority, so he decided to call elections at a time when he is assured of a win. He has kept a certain balance with his allies on Syria, while within the country he has kept a handle on the opposition. From an economic standpoint growth remains robust so elections need to take place before the domestic situation takes a downturn, i.e. before the summer. With the Turkish lira’s decline, his reelection and formation of a government have just become more complicated.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog