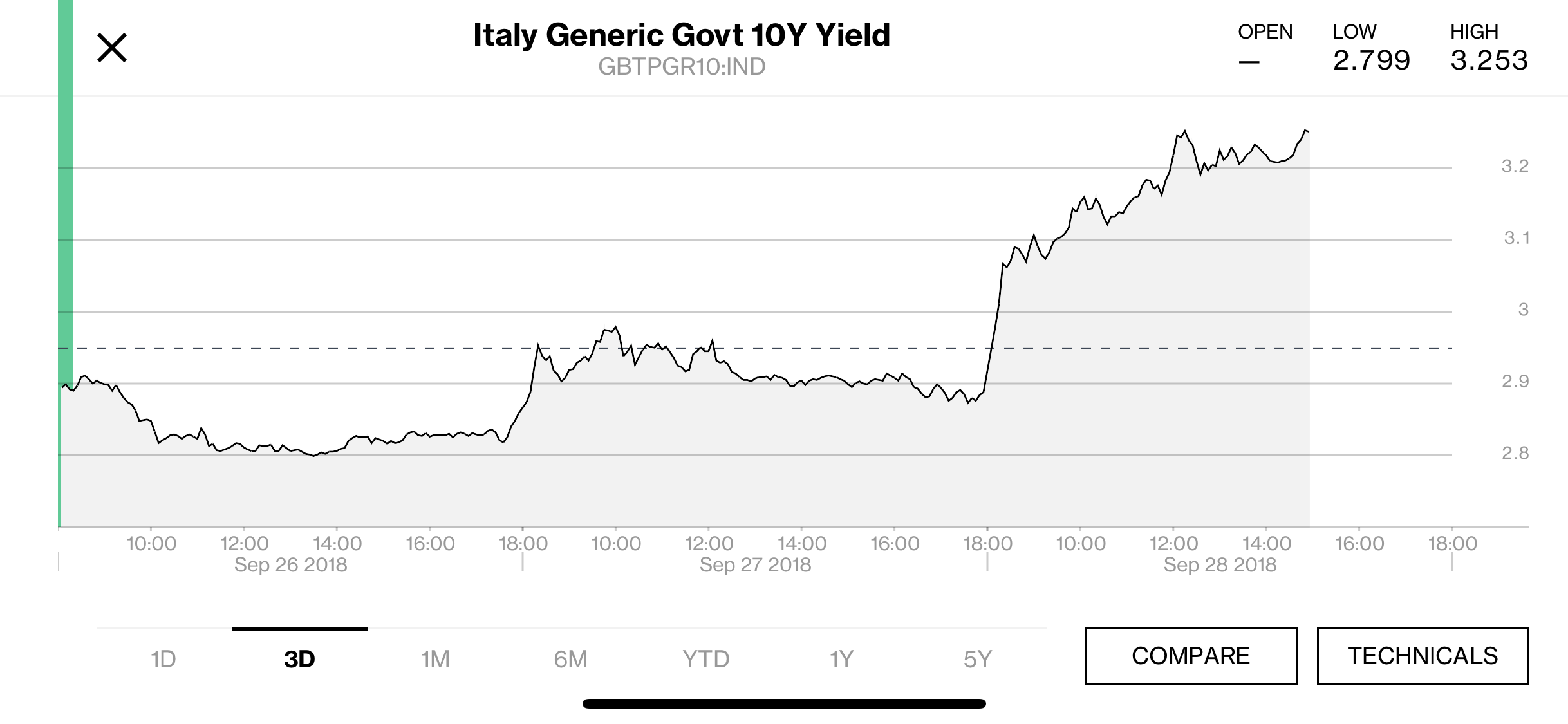

The Italian budget program, which sets out a budget deficit of 2.4% of GDP for 2019, 2020 and 2021, did not go down very well with investors. Uncertainty on Italy is making a comeback and the yield on the 10-year government bond rose sharply as shown by the chart below (as at 15.00pm CET today).

Source: Bloomberg

So just what are investors worried about?

1 – It is worth taking a moment to revisit one issue – the coalition government emerged from a watershed vote in the March 4 elections, so it was unrealistic to think that it would step into the shoes of the previous government.

Giovanni Tria’s appointment to the ministry of economy and finance was a way for the Italian government to look like it had a grip on the situation.

The previous government had cut back the deficit to 1.7% in 2018 according to the European Commission’s projections, yet if we are realistic, it seemed unlikely that the budget deficit would be set at the 1.6% that Tria wanted, in light of this political watershed.

2 – We do not yet have details on the macroeconomic framework for this budget, and the trends for both growth and inflation will dictate whether the public deficit can remain set at 2.4%: this is a major source of concern.

The macroeconomic framework will be announced around mid-October when the budget is presented to the European Commission, but an overly optimistic growth profile would soon dent the credibility of the budget targets set.

3 – Budget measures already outlined will not provide any growth stimulus or set Italian output onto a clear uptrend.

Productivity has been trending at a near-zero pace since 2000, which means that the Italian economy is unable to generate a surplus from production, and this is the most worrying issue for the country (see my post here) as it reflects its inability to intrinsically make progress towards high and robust growth in the medium term.

Looking to the budget program presented, a few measures are particularly worth noting:

- €10bn for basic income will help drive consumer spending, especially in the south of the country.

- The 2011 pension reform will only be partly reversed at a cost of €2.5bn – this is not a supply-side move but rather an additional cost for the economy.

- The flat tax plan was outlined but with no details – this is not a supply-side measure either.

In other words, the budget measures will not trigger any fresh impetus for output, yet production is Italy’s Achilles heel, so details on the macroeconomic framework will be key.

4 – If this framework indicates an overly optimistic and therefore not very credible scenario, we will see renewed uncertainty and concern on Italy, as it would cast doubt over the 2.4% deficit figure, which would rise and could potentially move towards 3%. Public debt could then also surge, with the ensuing uncertainties on the country’s sovereign debt rating.

5 – This would be extremely worrying as it would be a sign that the Italian government does not have a real grip on public finances: allowing the public deficit to spiral up and out of control in a sluggish economy that has not undergone a recessionary shock makes for a very difficult situation to manage.

6 – The European Commission may intervene, although the risks are small.

There are two issues worth mentioning in this respect:

The country would not move towards the budget balance that is the very cornerstone of European budget policy. If the deficit is maintained at around 2.4%, the Commission may reprimand Italy but has no real leverage to impose penalties. However, it would be interesting to see how the situation plays out: European budget rules are implicitly based on cooperation, especially in the euro area, but the Italian government is very clearly taking a very different path. The Commission would have to be inventive and a large country refusing to play by the rules in the long term would put European integration under pressure.

The Commission could implement an excessive deficit procedure for the country, but once again there are no real sanctions. After all, it adopted this procedure for France from 2009 to 2018 with no real consequences for the country, so there is no reason to think it would be any different for Italy.

7 – The real difficulty if the budget spirals out of control and moves towards 3% is that investors would lose faith in the country, leading to funding difficulties, followed by a rating downgrade that would only serve to bear out investors’ concerns.

Italy derives 35% of its financing from foreign investors, which is substantial, but it has a current account surplus of 1.8% of GDP, which reflects higher savings than investment, and this may act to cushion the effects of investor wariness on the country.

These is one safeguard – in the event of financing difficulties, Italy would have to call on the ECB and the European Stability Mechanism. It would of course be eligible for financing assistance, but in exchange for severe restrictions on public finances. The political programs currently being implemented would most certainly not be approved by the ECB or the ESM, and Italy does not have the wherewithal to leave the euro area (the UK example comes at an opportune moment), so the Italian government would have to give in. A middle road that avoids excesses and does not wreak havoc in the euro area as a result of Italian debt restructuring would be the ideal situation.

The main danger is that the Italian economy is not playing by the rules of the European game, and this means that institutions have to bend the euro area framework to keep it in place: this is a no-win situation for all concerned.

Wariness on Italy is based on inadequate information on the macroeconomic framework, which will be presented in mid-October, so we are set to see severe volatility on Italian assets as further information emerges, and banks will be particularly affected.