The United Kingdom will officially leave the European Union tonight. The country made a political choice – rather than an economic decision – when its people decided to exit the EU, and this political aspect is set to continue dictating the choices made by Boris Johnson.

Brexit is first

and foremost a political decision that reflects the will of the British people to

“take back control”, and so their decision to exit the European Union should be

considered with this aspect in mind. British society viewed membership of the

European Union as a hindrance.

Their decision was in no way dictated by economic considerations, although

these aspects may of course have been taken into account when considering

decisions. However, Brexit cannot usefully be seen as an economic choice rather

than a political one.

During the campaign leading up to the referendum on June 23, 2016, economic arguments that highlighted the potentially severe impact that Brexit would have on growth failed to sway voters. The various scenarios outlined by the London School of Economics and the UK Treasury pointing to a sharp deterioration in GDP had no effect, as discussions of economic risks never managed to rival with the political agenda.

The debate at the time mainly focused on the UK restoring sovereignty – particularly on immigration policies – rather than considering the economic impact of the referendum. The press also mirrored this focus as economic aspects never made it to the front pages for any length of time.

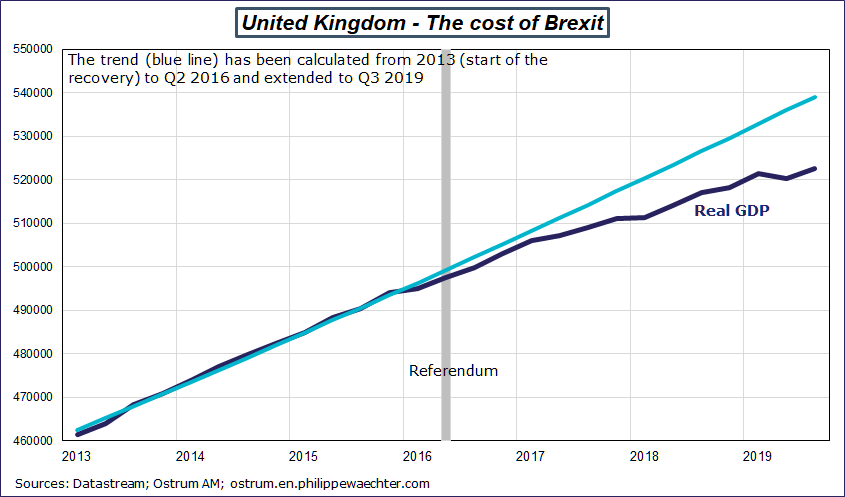

Over the three years that followed the referendum, events proved British voters right: the economic risk that was highlighted was not deemed to be relevant as there was no economic disaster. Yet the gap between recorded GDP and the trend calculated from the recovery in 2013 to the date of the referendum developed and increased over time, reflecting the cost of Brexit, which is already substantial.

However, the UK will only effectively exit the EU as of February 1, so the full analysis of the economic impact is still to come.

Brexit has polarized British society, with each citizen forced to have a stance on the matter: this necessary choice then dictated all other decisions, including economic aspects. Alberto Alésina, Armando Minao and Stefania Stantcheva (see here) demonstrate the same phenomenon using US data. Analysis and interpretation of economic data are influenced by the polarization of politics, with cognitive bias depending on the reader, leading to a failure to conduct an objective analysis of economic facts.

This analysis could no doubt be applied to the UK after the Brexit referendum and in particular the way Boris Johnson then implemented the outcome of the vote. The Prime Minister’s political career has been characterized by his ability to adapt to suit changes in the country’s mood. He will tailor economic policy to match voters’ expectations, and has already broached the matter as regards healthcare spending.

So any number of outcomes are now possible, as economic choices are no longer driven by merely rational or ideological criteria, but rather they are shaped by the political agenda of the person making the decision, and depend on what s/he believes voters want to hear.

One very immediate upshot of this situation is that a great deal of uncertainty still remains on the UK’s position with relation to the European Union. No decision has been made on the UK’s future relationship with the European Union: will it be based on maintaining access to the single market, with the advantage of keeping the UK in the European value chain, or will the country entirely break away from the European Union? We can argue that the first option is the most rational and also the least damaging for both the UK and the EU, but it all hinges on the UK government’s – and particularly Boris Johnson’s – perception of what voters want. It looks most unlikely that a large diversified economy like the UK will dance to Brussels’ tune and bow to its decisions over the long run.

Boris Johnson wants to “get Brexit done” by the end of 2020, which is a very tight schedule. It took more than three years to sign the divorce agreement, so will 11 months be enough to come to a detailed arrangement on the relationship between the two parties? The December 31 deadline for the end of the Brexit transition period will come around very soon, so the risk of a hard Brexit still remains.