The stagflation risk in Europe

In Western countries, there is renewed risk of stagflation. Uncertainty related to the conflict could lead to delayed investment or consumption expenditures weighing on the growth momentum. This would not reverse the strong growth trend but could erase part of the strong dynamics seen at the end of 2021.

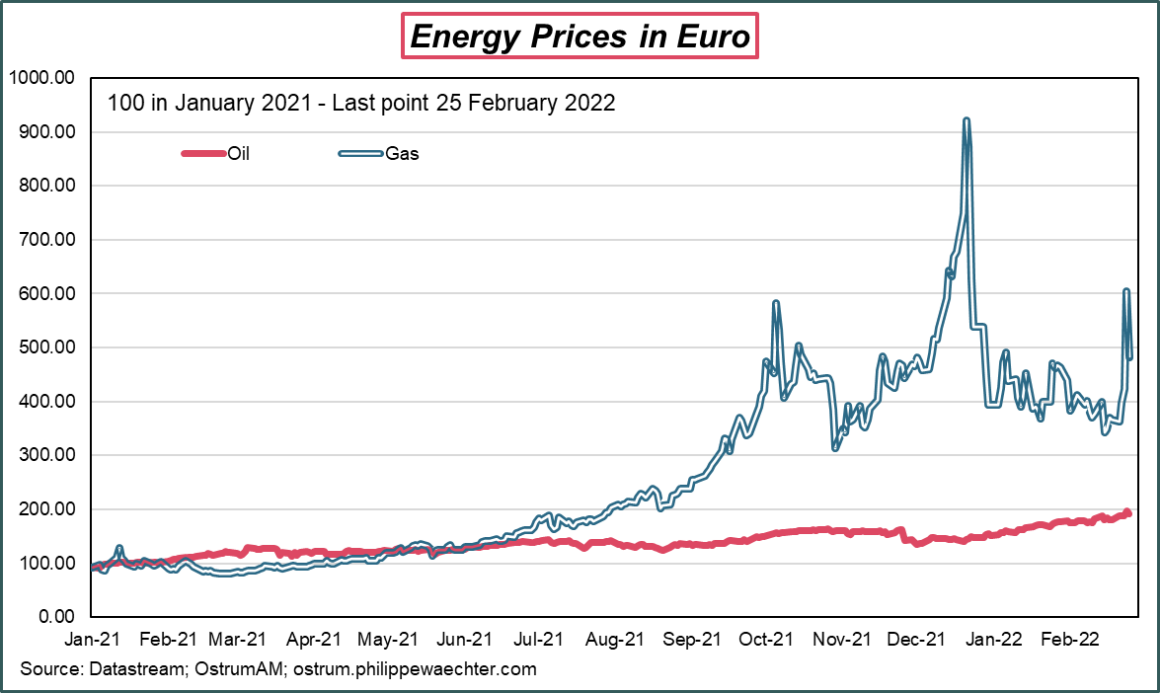

Energy prices will continue to be high. This is already the case with oil, above 100 USD for a barrel, and this is now the case for natural gas. Since the start of the conflict, the natural gas price has jumped. The energy contribution to the inflation rate will remain high in coming months. In January 2022, it explained more than half of the inflation rate (the inflation rate was 5.1% and the energy contribution was at 2.7%).

Food prices also jumped after the attack notably on wheat. (Russia and Ukraine are two important exporters). The main risk is a reduction in production in Ukraine for wheat, corn, barley and sunflower (and its oil 1st producer). The food contribution to the inflation rate will creep up in coming months.

The inflation rate will therefore remain high for a longer period than expected by the European Central Bank. In its previous forecasts, the ECB said it expected an inflation peak during the first half of 2022 before a convergence to 2% (its target). The peak will be later and the convergence may be longer than expected.

Therefore, the loss in purchasing power will be larger than expected. Consumers will have to make an arbitrage between energy and goods and services expenditures. As it dampers demand, this will weigh on the European expansion.

The ECB will not move at its next meeting on March 10th. As uncertainty is growing with the length of the conflict, the ECB mustn’t add more risks on business by announcing a tighter monetary policy in a foreseeable future. Every investor keeps in mind that the ECB will change its strategy as soon as possible after the conflict.

In the Euro Area, the risk is lower growth and higher inflation compared to what was expected at the beginning of the year.

The width of the adjustments will depend on the length of the conflict. A short one will not have too much impact but as long as the conflict continues, the uncertainty increases lowering the momentum.

The main impact on this crisis may be on wages. If the inflation rate is higher for longer than expected, then workers may ask for an inflation premium to limit their loss of purchasing power. This kind of indexation is what every central banker and minister of finance want to avoid as it creates persistance in the inflation rate and lower flexibility in the adjustment process.

Our current forecast is 3.5% for 2022 in the Euro Area, it could converge to 3% (this is not a good performance as the carryover growth for 2022 at the end of 2021 is 1.9%).

Our current forecast for the inflation rate is 3.5% on average for 2022. It could converge to 3.8% with a robust energy contribution.

The impact of sanctions

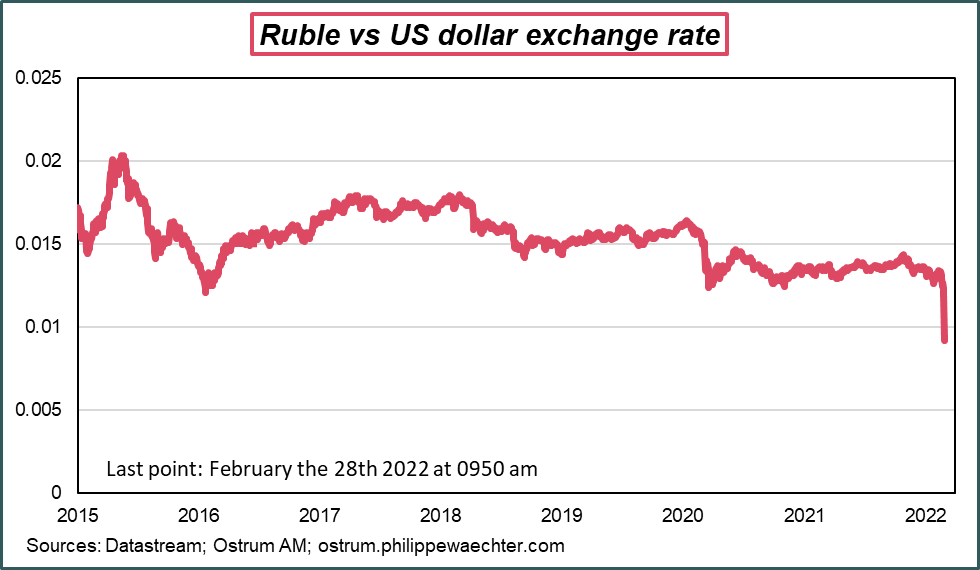

The sanctions on the Russian central bank will limit its ability to intervene, particularly on the foreign exchange markets and cause the Russian currency to fall. Westerners are fleeing Russia. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund leaves Russia, BP sells its shares in Rosneft. No one in Western countries wants to hold rubles anymore.

This will result in more inflation since imported products will cost much more.

The inability of banks to use Swift and therefore to finance Russian exports and imports will weigh even more on the availability of products in Russian shops, accentuating inflationary pressures. This fragility of the banking system is already causing queues in front of the banks. The Russians want their assets back.

A direct consequence of the sanctions is that the central bank will have to issue more money to finance government spending and its budget deficit via the additional cost associated with the conflict.

Rising inflation, weakened banks and a spendthrift central bank without counterpart, this is the recipe for creating the conditions for a flight from money. This will be accompanied by a risk of hyperinflation. In the past, the central bank had not been sanctioned in this way. This is why the period is particular and specific and why the flight from money quickly becomes a reality.

Russians will get poorer, but they will know that the root of the problem is Ukraine’s aggression. The people can revolt. It seems unlikely, as it seemed unlikely in 1980s Eastern Europe before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It is interesting to look back at how things may have unfolded in October/November 1989.

In a paper published in the American Economic Review of May 1991, Timur Kuran* theorizes what happened, that is to say the sudden break that took place at that time.

A few weeks before November 9, 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the demonstrations against the regimes were not very dense. Then all of a sudden, they grew to an incredible size, sweeping away the institutions in their path. Over a very short period, the size of the protests went from marginal to out of control. Faced with this human tide, governments gave in. It is this non-linearity that must be understood.

The author suggests that every citizen of Eastern Europe had a private opinion about their perception and judgment of the regime. This opinion remained secret. He also had a public opinion which he expressed in society. The two opinions could be identical or opposite.

At the start of the demonstrations, the fear of repression implied a small number of demonstrators, even if everyone’s private opinion could tend towards questioning the regime. The context of the time in the USSR with Gorbachev created, as never before, the conditions for possible change. The political regimes are tossed about, they don’t all react the same way. Over time, which is very short, the risk associated with repression decreases, the demonstrators are a little more numerous but they are not in the majority. Then at some point, the fear of repression disappears and there, in a few days, the number of demonstrators increases almost without limit.

Political power is overwhelmed and scuttled. It is this non-linearity that is important. In a very short time, everything can change. This is what happened in Eastern Europe in November 1989.

The sanctions on the banking system and on the Russian central bank will create the conditions for destabilizing society and the Russian economy. This situation could fuel private opinion. As long as the risk of repression remains high, protest will be limited. We cannot exclude that the Russian people will form a mass against the regime even if this behavior is not part of Russian history. But the Russian citizen is no longer as alone as in the past and he knows that war is unpopular all over the world and he also shares this rejection of conflict.

A scenario that would look like that of Eastern Europe in 1989, based on the loss of bearings in a collapsing society while repression is no longer effective, can be envisaged.

Such a situation would force Putin to refocus his action on Russia and abandon Ukraine. It is not surprising that Putin raised the nuclear threat after the measures taken by the West.

The situation in the next world will never again be the one we knew. But there is a non-zero probability, in my opinion, that the Russian regime will change with the help of the West. For the moment the probability is reduced but in September 1989, it was just as much.

______________________________________

*Kuran, Timur. “The East European Revolution of 1989: Is It Surprising That We Were Surprised?” The American Economic Review 81, no. 2 (1991): 121–25.