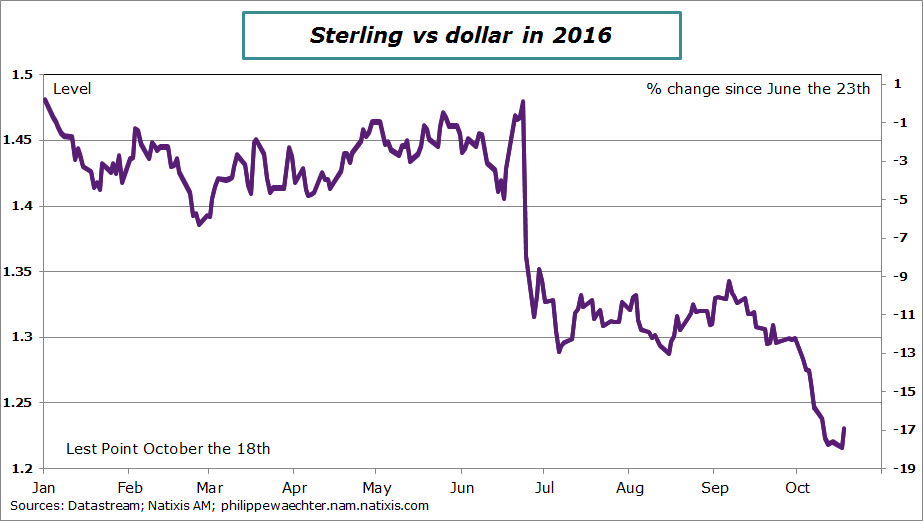

Sterling’s decline is the most visible effect of Brexit so far. It has shed close to 17% against the dollar since the referendum, and more than 14% to the euro as at October the 18th.

We can identify two phases to this trend: firstly, in the wake of the referendum on June 23, and secondly after Theresa May’s speech to the Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham on September 30. She announced that the United Kingdom would officially notify of its intention to leave the European Union by March 2017 at the latest

(the rally on October 18 was due to the possibility that the UK Parliament could vote on the treaty after negotiations are complete.)

Two comments can help understand the reasoning behind hard Brexit.

The first is the United Kingdom’s aim to be a fully independent, sovereign country. In other words, in Birmingham Theresa May implied that she does not wish to depend on European laws for the British economy and society to function after the country leaves the EU. This automatically rules out a framework for talks that is similar to the Norwegian or Swiss model.

The second point is the firm stance expressed by Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, who stated in a tweet that it is either hard Brexit or no Brexit.

@eucopresident Brussels, Belgium

The only real alternative to a “hard Brexit” is “no Brexit”. Even if today hardly anyone believes in such a possibility.

This implies that access to the single market would not be an automatic provision of the treaty for the UK, and hence the European passport will also be called into question.

This has two short-term consequences

1 – The appeal of the UK economy would dwindle as one of its attractive features is its access to the single market. Theresa May’s desire for independence severely reduces the shared momentum between the UK and the EU.

2 – The City had previously benefited from the European passport and will be hampered as London will become less attractive as a financial center. Furthermore, London’s attractiveness will also depend on the status given to other European nationals who work there. If they suffer a serious downgrade to their status compared to the current situation, it may no longer be in their interests to stay in London. This could potentially lead to a severe loss of human resources, which would dent growth and further weaken the British financial sector.

So the British problem is threefold, plus a fourth point.

The first is the negative impact of the end of access to the single market under current conditions. The removal of the European passport will heighten this negative impact.

The second is that sterling’s decline will considerably increase the economy’s competitiveness, particularly areas of the economy that are not directly dependent on the City.

The third factor is the acceleration in inflation which will dent household purchasing power.

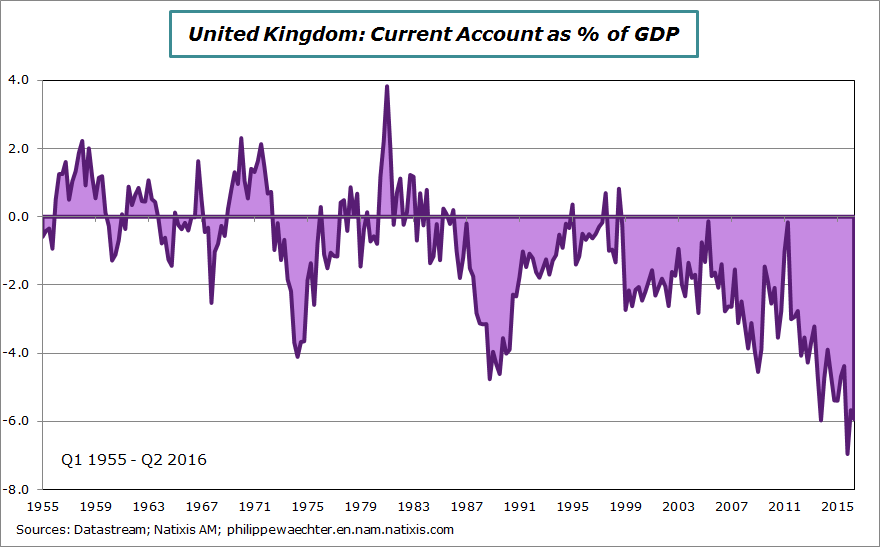

The last point is the sum of the above, and involves the sustainability of the UK current account, which currently carries a deficit of around 6% of GDP and is financed by the rest of the world.

The European Union is the UK’s main trading partner. The change in trade regulation due to the end of access to the single market will create a shock for the British economy. We do not yet know what agreements will be implemented after article 50 is triggered, but it is highly unlikely that trade will continue as it is today, so the shock for the UK economy is set to be a negative one.

The decline in economic activity resulting from the end of the European passport will drag down revenue momentum in the City. Furthermore, a large proportion of euro-denominated business (e.g. clearing) would have to be relocated to the Eurozone, further denting the City’s revenues.

There are several points to raise on these issues.

The first is that the decline for sterling is an advantage for the rest of the British economy outside the City: sterling’s strength over recent years can be seen as a reflection of the intensity and extent of financial flows and investment into the City. However, this situation dented the rest of the UK, as strong high sterling was a constraint for other regions and hampered investment.

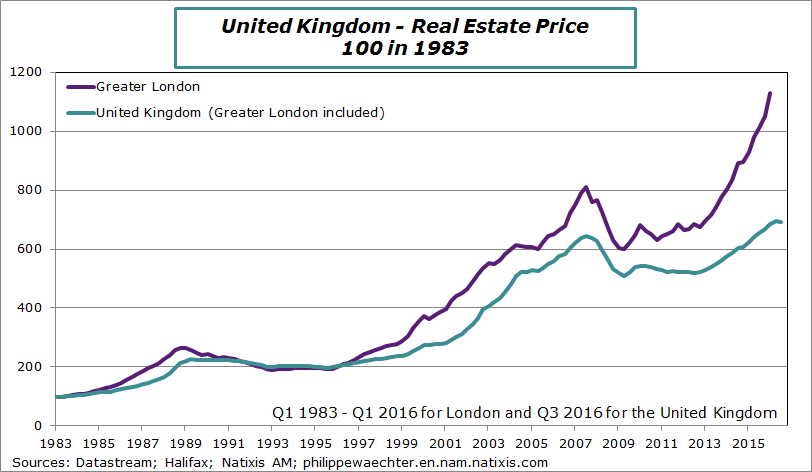

One way of analyzing this situation is to look at real estate prices in London compared with the rest of the UK. The gap is huge and reflects lower competitiveness outside London.

So sterling’s decline should create a comparative advantage for UK industry and this is the option that the government is seeking to develop as it does not want to depend on the European Union but rather set up agreements on specific sectors.

Sterling’s decline should therefore boost competitiveness and promote investment in the UK economy, thereby offsetting the loss of revenues resulting from more sluggish business in the City.

So the question has a number of answers

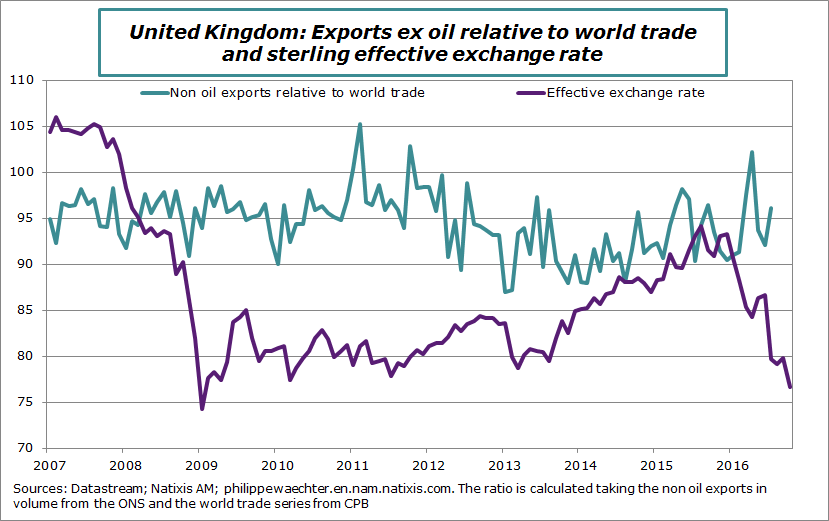

1 – Sterling’s decline will not necessarily bolster exports. Sterling’s real exchange rate trends over the past 10 years have not boosted British exports as compared with world trade, as shown in the chart below. Wide fluctuations in sterling did not provide a strong advantage for exports (click here).

The Office for Budget Responsibility calculated in its model that a 1% price drop at export only led to a 0.41% rise in exports of non-oil goods after 9 quarters. This is very small, and is reflected in the chart.

Furthermore, world trade trends are slow. Over the year to July, trade contracted 0.7%. The UK economy will not be able to benefit from a positive external shock that would have been accentuated by sterling’s decline.

In view of these factors, we cannot expect a strong and sustained impetus from external sources.

2 – Beyond the remark above, competitiveness gains could encourage massive investment in the UK. This is unlikely, despite the fact that the British government wants to cut corporation tax as has been mentioned.

Negotiations on the UK’s access to the European market will be long and the results uncertain. In view of this severe uncertainty, it is unlikely that investment will increase swiftly. The first remark heightens this trend and increases investor inaction.

3 – Uncertainty is due to the size of the future market. If UK companies can access the single market without any restrictions (most unlikely) then there is a good reason to invest. However, if the target market is restricted to the British market, then there is no appeal as the market would be too limited.

A strategy aimed at offsetting the negative impact of weaker business in the City with a strong rebound for the rest of the economy is fairly unlikely to materialize.

This is particularly true as the lack of impetus and the negative shock from the change in trade regulation are set to lead to weaker job momentum than in recent years. This weaker momentum will have major consequences as wage growth will not cover the increase in inflation. Households will then lose purchasing power, failing to drive domestic demand and thereby reducing incentives to invest. Consumer spending will subsequently decline.

From another standpoint, this overall UK economic context does not seem compatible with an external deficit of close to 6% of GDP. This hefty balance cannot be reduced by sterling’s decline alone. We have seen that price elasticity of exports was low, and elasticity of imports is even lower (0.2% after 9 quarters). The external imbalance will not disappear by itself unless sterling depreciates even further. This looks possible if the economy’s response does not meet expectations, and this depreciation would lead to a further increase in inflation. This situation would be tricky for the Bank of England as the increase in inflation would not be temporary but would most certainly be more permanent.

There is the matter of financing this current account. It is usually financed by financial flows and investment, but will international investors want to invest in the UK if there is so much uncertainty? Certainly not. This means putting pressure on domestic demand in order to change the import profile and make the current account profile sustainable: in other words, we cannot rule out an austerity program.

Against this backdrop, the Bank of England will maintain its accommodative policy for such times as it feels the economic deterioration is only temporary and for as long as it thinks the economy will recover a more robust performance in the future. It may raise the limit for its quantitative easing operation in order to limit long-term interest rate rises. This will only work if the BoE feels the deterioration is temporary. If it thinks that the shock is set to be of a more lasting nature, then it is likely that it will adopt a tougher stance to shore up sterling. But that will not be for a while.

In a recent report by the UK Treasury, the government estimated the cost of Brexit for the British economy at between 5.4% and 9.5% of GDP out to 15 years compared with staying with the EU. The main scenario is for a loss of 7.5%.

Hard Brexit as sought by Theresa May will come at a heavy price for the British economy as it will lose part of its activity that was a major source of revenues (the City) and will refocus on an economy that will not take too much advantage of the depreciation in sterling, while domestic demand will weaken via a drop in purchasing power. This heavy price will be primarily paid by the middle classes, who tipped the balance in favor of Brexit in the first place.