Mario Draghi’s stance is guarded. His latest press conference gave no indication of the change in communication tone that we are set to see from the European Central Bank in January.

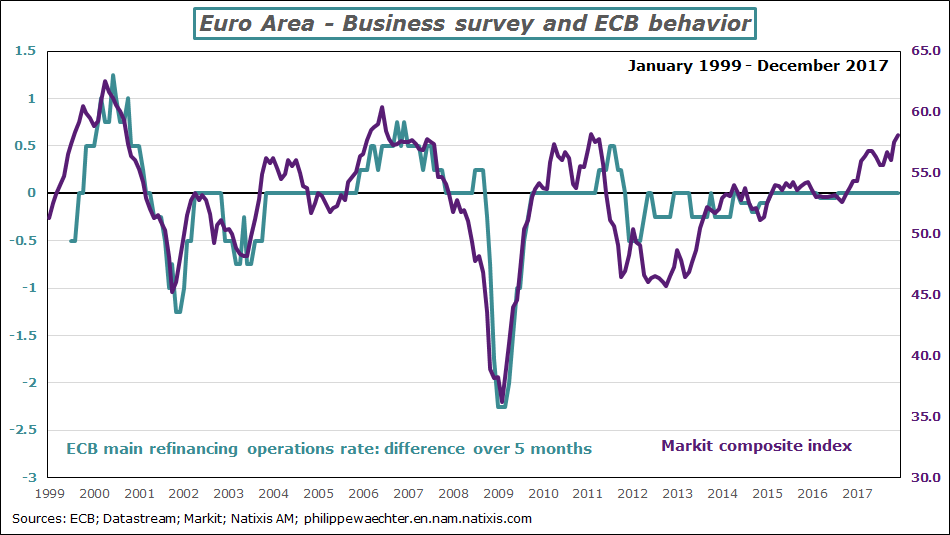

The ECB is finally taking on board the strength of the economic cycle and so its communication stance must adapt to this shift. This is rather good news, as the central bank constantly appeared to be acting in reaction to an environment that could swiftly deteriorate, and this shift can bolster our confidence in the strength and length of the economic cycle. The other point noted by the ECB is the move away from an exclusively inflation-based focus and towards a more broad-based communication tone. This implicitly means that the ECB is extending its reach, but really when it comes down to it, this was already the case: the ECB’s intervention has hinged on the economic cycle rather than inflation since the euro was adopted in 1999. The chart below shows the Markit composite index and the difference in the ECB main refinancing rate over 5 months, and reveals that changes in the second indicator are clearly dictated by changes in the economic cycle, rather than in inflation.

The ECB is picking up its old habits from before the 2007 crisis.

However, this does not mean that the ECB is about to change its monetary policy. The minutes from the ECB meeting do not indicate that change is imminent, but each observer will read into them as he/she wishes. In my view, the signs from the ECB are similar to signals from Draghi in Sintra at the end of June 2017, when he suggested that monetary accommodation would not last forever.

It is also worth noting that most members of the monetary policy committee agreed on the strategy being implemented. The key point for the months ahead will be the pace of inflation: beyond the impact of oil prices that are currently hitting the 70-dollar mark, will pressures emerge? This is a bone of contention for the ECB and economists. On the one hand, Peter Praet thinks that inflation will not pick up speed and the ECB will march on with its asset purchases even beyond the September deadline, while on the other hand Benoît Coeuré believes that inflation will reach ECB projections and allow the central bank to stop the APP by that date. Draghi is stuck in the middle, but I think that he tends more towards Praet’s viewpoint than Coeuré’s. The ECB is changing tone but analysis of inflation will remain a key aspect in monetary policy management.

The second point is the urgency that sometimes seems to emerge in monetary policy normalization.

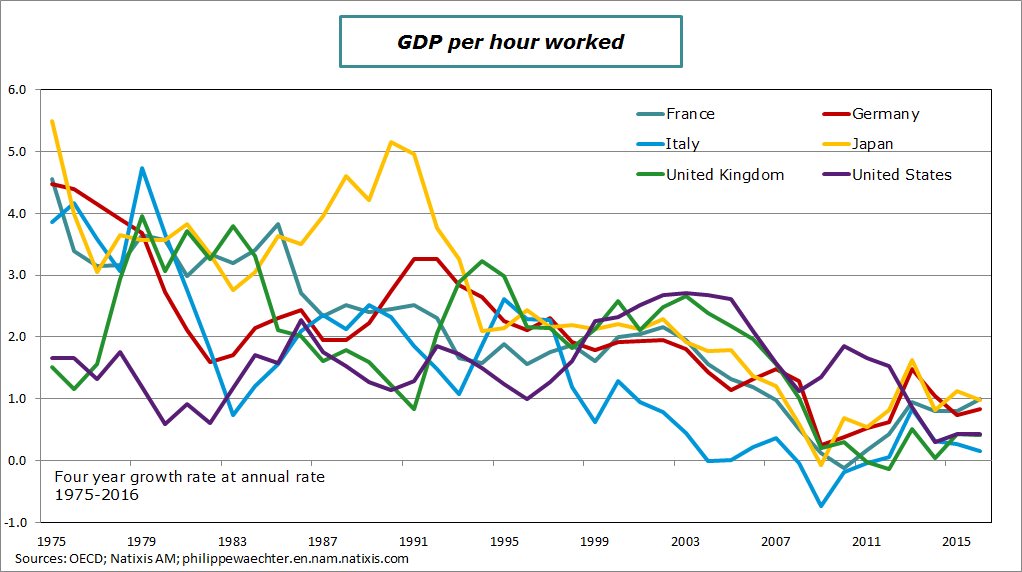

The robust growth we are currently witnessing is a result of low interest rates, which promote spending in the present and encourage debt in order to fuel demand, as is their role. However, we must look somewhat further. Western countries’ economies are now characterized by weak productivity growth, as shown in the chart below. This is a vital point, as per capital GDP growth is the sum of productivity growth plus job growth. Productivity was higher in the past and its strength led to a return to this robust trend.

Today’s productivity profile is lackluster at under 1% per year and the return to trend will be set to a lower course, which is why monetary policy normalization must take place at a moderate pace.

Any move towards faster-paced growth must come from stronger job creation. We can always hope for a shift in the productivity profile on the back of the slew of innovations that are transforming the economy, but this change has not yet materialized, and if it does, the adjustment would have to come from jobs, with the ensuing likely severe deterioration in labor market conditions. The UK is a good example of this, as recent per capita GDP growth was primarily generated by an increase in employment, while productivity plateaued (see green line on the chart), as reflected in the development of zero-hour contracts and self-employment. In other words, labor market insecurity became the new norm, and I do not think that this is the right way to go.

Central banks’ interest rate hikes will dictate demand, but supply does not seem able to embark on the virtuous spiral to adapt to this challenge via productivity. This will be our challenge for the months and years ahead – successfully navigating the knife edge between overly restrictive demand conditions and supply conditions able to ensure smooth development.

Lastly, the third point worth analyzing is the agreement to form a coalition government in Germany.

This important accomplishment reduces political uncertainty for our neighbors and more significantly, the agreement also lays out changes for Europe. The SPD pulled off quite a feat when the CDU agreed to a European budget and the European Stability Mechanism’s revamp to become a European Monetary Fund that can act as a debt restructuring mechanism. This move marks Germany’s agreement to the idea of pooling funds. In other words, reforms required to shore up the euro area in the long term are back on track once more. The Franco-German partnership will be able to implement a program of reforms for the European institutions and put paid to a populist backslide for Europe.

Euro area investors keep a close eye on the growth momentum that the ECB has just confirmed and also pay great attention to the various reforms that the Macron/Merkel duo is likely to implement. Over recent weeks, doubts have been prevalent on Europe’s ability to stage reforms in the absence of a German government, but these doubts have been swept away, paving the way for an economically and politically stronger Europe in the long term.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog