China has played a major role in all of the stock market fluctuations seen in recent days. However, analysis of this should be discriminating. The Chinese economy has not suddenly collapsed, it is more the Shanghai stock market that has adjusted sharply downwards.

A clear distinction should be made between the two phenomena and we should keep in mind that stock market fluctuations are always excessive relative to economic movements. Paul Samuelson, probably the most influential economist in the post-war period, indicated that the stock markets had forecast nine out of the last five recessions.

The Chinese economy is no longer that which enjoyed growth of 10% a year over two decades. The development of a sizeable middle class has radically changed its growth model. This middle class has other needs than those noted in an economy that is taking off. China is currently in this transition phase. It needs to adapt its economy to more diversified growth with a larger share for services.

This transition is causing and will continue to cause a lower growth rate. If the Chinese economy’s profile follows that of Japan and South Korea, in around 10 years, GDP should therefore grow in range of 3-5% a year.

This switch to a more advanced economy is complex and is prompting upheaval. The economy is changing shape, new businesses are being created and eliminating older ones. This type of rupture necessarily causes resistance. In a country like China, state institutions are very present, especially via state owned enterprises. However, these are lacking in efficiency and the changes taking place are massively altering their positions in the decision-making chain. In other words, resistance to change is very present and policies favoring debt have sought to maintain the previous situation rather than facilitate the development of fresh momentum. This has not helped state-owned enterprises to perform better and these are lacking in productivity and profitability, thereby hampering the development of new activities. The Chinese crisis lies in the difficulty of this switch-over. Resistance, especially on a local level, is high since these rifts change the structure of power.

The latest signal from the authorities was the depreciation of the Chinese currency or how to try and create a positive shock on business by attempting to restore competitiveness in a model that is too old to react.

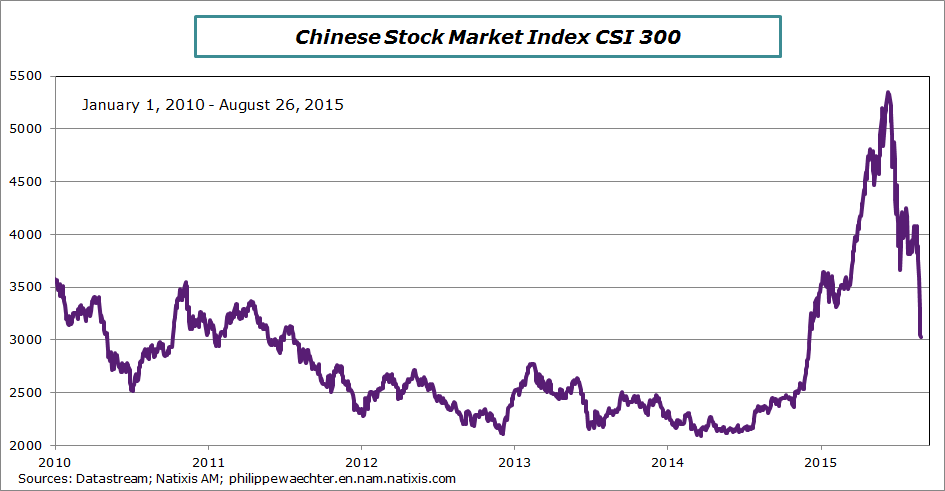

The Shanghai stock market benefited from a change in regulations in November 2014, making it easier to contract debt to buy equities. Chinese citizens, who like gambling, rushed at the chance and the market took off. At its peak on June 12, 2015, the Shanghai market had rallied 92% relative to the index average during the last quarter of 2014.

This increase did not reflect economic prospects since questions on growth were already present and valuations of Chinese equities looked excessive according to all the criteria used by analysts.

On June 12, the authorities changed the regulations and financial facilities were reduced. As such, those that bet on an additional upturn in the market to borrow found themselves restricted and obliged to liquidate their positions. The market went into nosedive. The Shanghai market then witnessed wide-scale adjustments although this did not affect western market places.

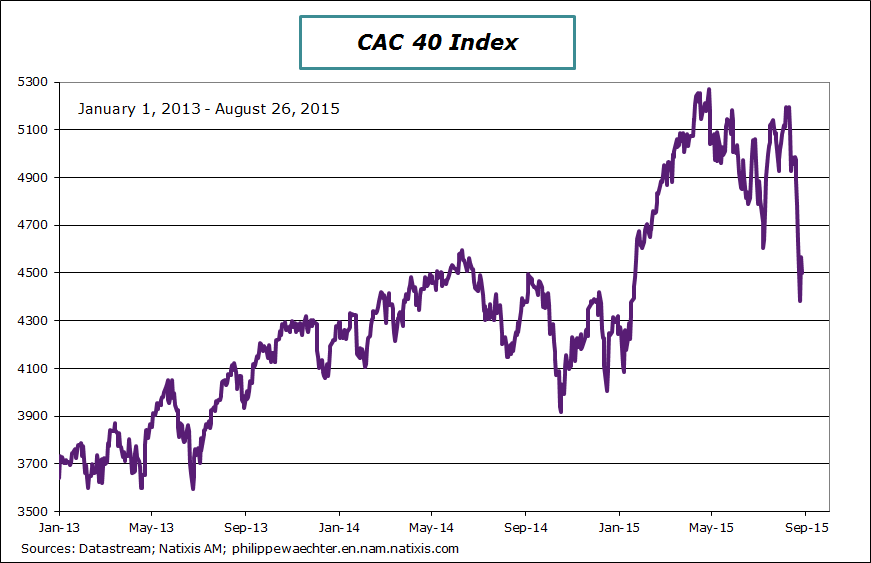

The combination of the adjustment in the yuan in mid-August and these recent fluctuations is what triggered the spectaculars movements seen on global stock markets.

These reflected not only uncertainty concerning the Chinese economy but also the idea that global growth could be slow for longer than had been estimated so far.

Concerning the first aspect, an assimilation was made between the stock market downturn and a strong turnaround in the Chinese economic situation. This is abusive reasoning in view of what we have discussed above. It does not imply that the Chinese economy is healthy, since it is in a transition phase, but it does not mean either that it is about to collapse. On the evening of Monday 24th August, comments assimilating the stock market downturn to an about-turn in economic momentum were impressive. This was not coherent. The Chinese market is set to remain volatile and we cannot rule out temporary contagion effects. Neither can we avoid a surge in uncertainty that is bound to emerge at some time or other.

This means that analysts have started and will have to revise their corporate earnings growth forecasts for coming years in light of the prospective change in global growth. This is bound to cause uncertainty on the markets.

Numerous questions have concerned economic contagion and the impact on European growth. Chinese growth is tending to slow and clearly the rest of the world needs to keep this trend in mind. This means that we can no longer count on China as a turbo driver for global growth as has been the case since it joined the World Trade Organization. As such, as I recently stated in my blog (here), growth in each region is set to be more dependent on local management of domestic demand. The equilibrium model is changing and effectively, but as a trend, needs to take account of the slowdown in the Chinese economy.

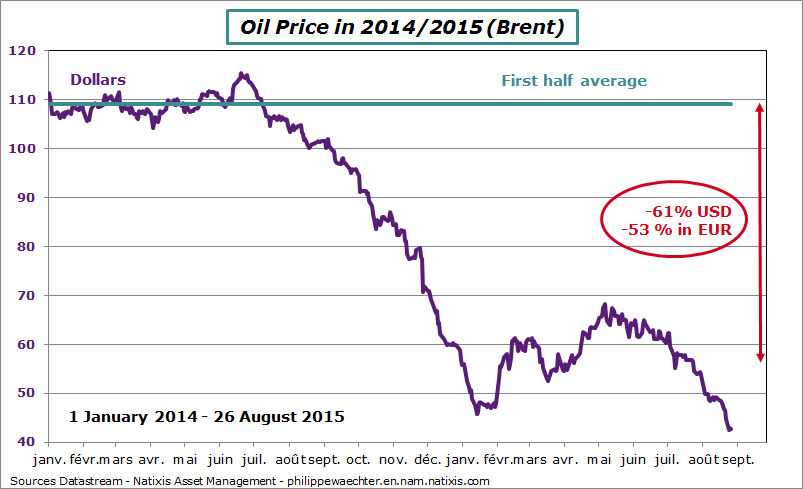

The effect should be positive for Europe and France. Consumers in France and in Europe are more sensitive to an increase in their purchasing power prompted by a fall in energy prices than by the downturn on stock markets. Oil prices could fall further relative to the USD 40-45/barrel noted in recent days.

During the Asian crisis at the end of the 1990s, oil prices plummeted to less than USD 10. While this prompted Russia’s bankruptcy it was nevertheless an excellent catalyst for growth in Europe and in France in 1999 and 2000. If European countries do not constrain domestic demand by restrictive strategies, then 2016 could be a genuine year of recovery for both Europe and for France.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog