Judging by the Italian president Sergio Mattarella’s (justified) refusal to approve a government that would have been dominated by the League with its aversion to Europe and its institutions, the forthcoming parliamentary elections in Italy will focus on the euro and Italy’s membership of the euro area.

The worrying point here is that the Italian population is no longer in favor of the euro, as shown by the latest European Commission Eurobarometer survey (October 2017), when 40% of Italians said that the euro is a bad thing for the country as compared to 25% of the population in the euro area as a whole, and also in France. Meanwhile, only 45% of Italians think that the euro is a good thing for the country vs. 64% on average in the euro area and France. The European question played a major role in the French electoral campaign in spring 2017, but we can see that the European aspect of the Italian elections was driven by different considerations. Close to half of Italians are skeptical on the usefulness of the single European currency, and herein lies the real difference.

The League will most certainly use this issue as its electoral platform and this will lead to a division of political opinion in Italy. The question now is who will fly the flag for the euro across the different Italian parties – the Democratic Party would have the credibility, but who would be its partner …can we expect Berlusconi’s Forza Italia to spearhead a campaign in favor of the euro?

One key point worth noting here is that Mattarella’s veto can only work once, and he cannot take a stand forever against any anti-euro anti-European government. So it is vital for action to be taken in Italy to steer the country away from this shaky ground.

The Italian situation is very different to matters in Greece, as unlike Athens, Rome is not playing host to the ECB-IMF-European Commission troika to manage its economy: Tsipras’ government at the time had very little room for maneuver.

The choice now facing Italy is essentially a political one, over which Brussels and the European Commission have little real control. The scale of the issue is also very different: Italy is the third largest economy in the euro area, and exiting the bloc would send shockwaves across Europe and through every level of its institutions… But it hasn’t come to that yet and there are still a few months to change the current perception.

The Italian crisis is also not a replay of the 2011/2012 sovereign debt crisis. A number of countries in the euro area had been hit by the collapse of Lehman Brothers at the time, as public debt rose quickly, public deficits soared and banks were hampered by portfolios largely made up of public debt with falling prices. The question was how – and how fast – countries affected could address this multi-dimensional shift and get themselves out of the quagmire. The most straightforward answer was to throw several countries into recession and this idea of purging the economy still holds sway, despite the fact that it doesn’t work, but it does give the (completely false) impression that things are moving in the right direction. Any notion of exiting the euro area was far from the majority view, which is why so many were willing to accept sacrifices. Then Mario Draghi came to the rescue before the euro area could break up, making the ECB the lender of last resort.

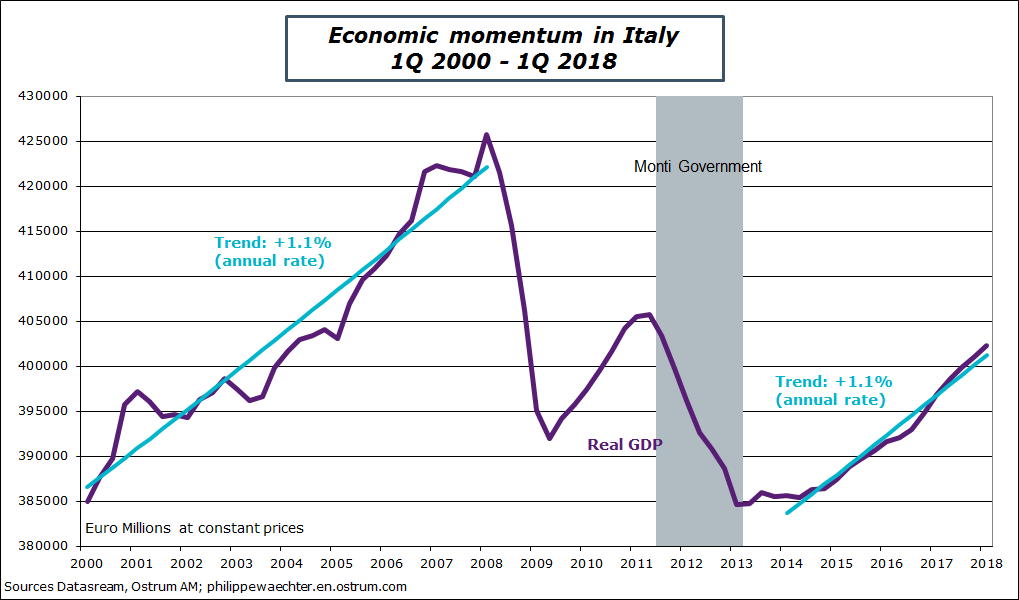

The economic situation in Italy is very unsteady for the reasons I mentioned here with a tendency to favoring an exit from the euro area. But the foundations are not the same. The Spanish political crisis we saw after tensions over the weekend is primarily a result of doubts on Mariano Rajoy’s credibility to lead the country. The Eurobarometer survey displays no doubts on the importance of the euro in the country, with only 23% of Spaniards thinking that the single currency is bad for Spain vs. 65% seeing it as a good thing. Meanwhile, economic momentum in Spain is not comparable to Italy (see first chart here ).

However, there is one major risk – from a distance, onlookers can perceive Italy and Spain as identical.

Italy is poised to have a technocratic government. Mario Monti also presided over a technocratic government between end 2011 and early 2013, and his legacy was not necessarily a positive one, as shown in the chart. But he cannot be held responsible for everything and this is the very problem of a technocratic government – it cannot take bold decisions to trigger a sea change.

Cottarelli, known for making cuts to public spending, cannot obtain a majority.

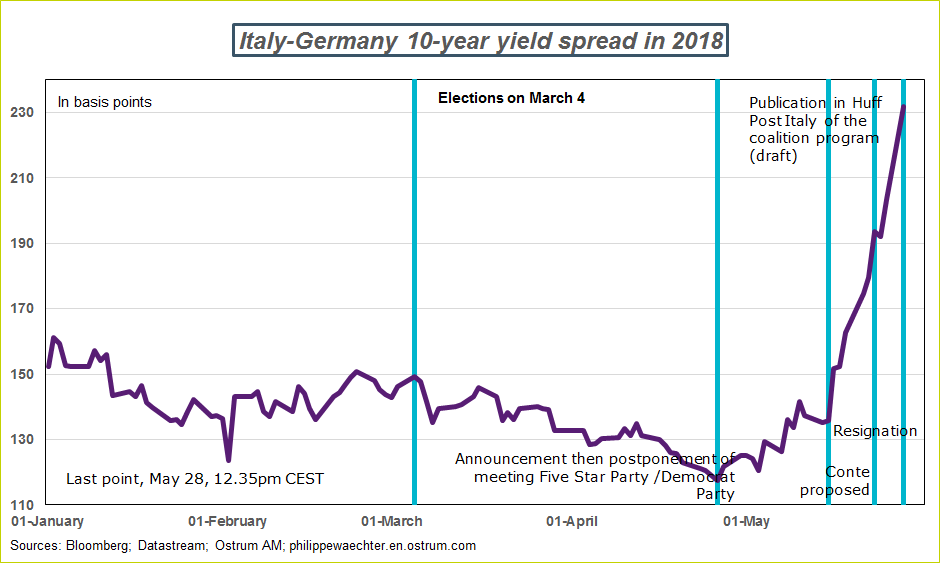

Italy’s performances on the markets improved today in early trading, but this momentum petered out and the spread with Germany widened very quickly towards 230bps.

In view of the risks, the markets are not pricing in high risk, as investors tend to think that a sensible solution will be found in the end, so there is no need to take excessive plays. But perhaps this very approach itself is excessive…

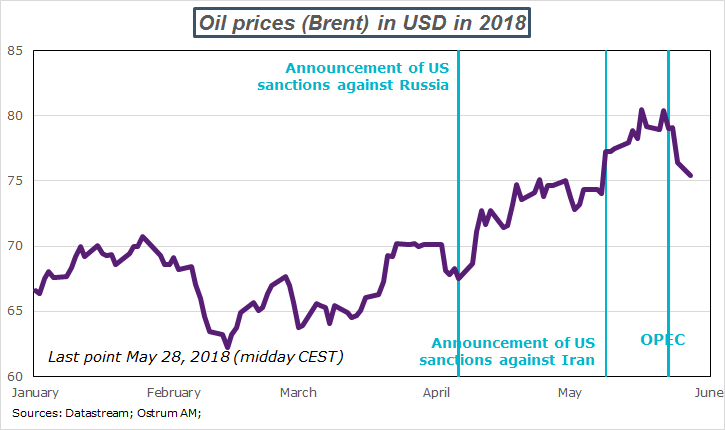

Oil prices have been easing since the end of last week. OPEC members are willing to raise production and avoid putting excess pressure on the market. In the current oil market, it is interesting to note that demand is solid in light of robust world growth, so any news on the market affects oil prices. The chart below shows that market shifts occur when specific decisions are taken. In the past, when Saudi Arabia, Russia and others decided to cut production, it didn’t have much effect as demand was sluggish, but this is no longer the case and this changes market trends. This means that we are not heading straight for USD100/bbl, but rather prices will make a pit-stop around USD75, as market adjustment will be supply-based and excessive prices would be bad news for world growth.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog