The whole document is available in pdf format September round-up of the summer_s events

Let’s start with the global outlook – are signs on the world economy still as robust as they were?

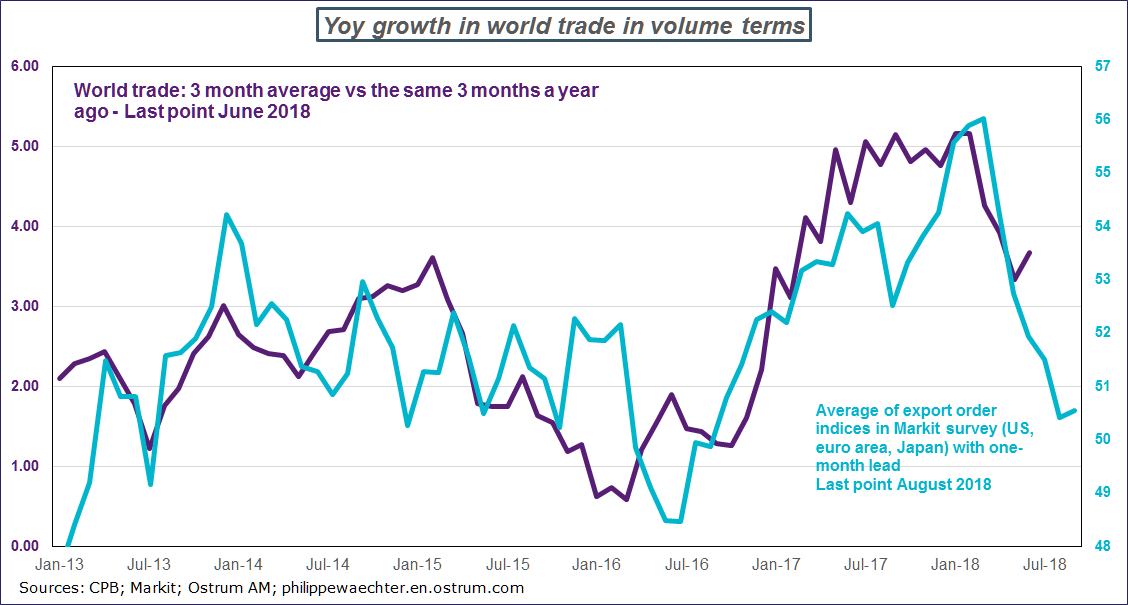

The situation has changed since the start of this year. The world economy was fuelled by faster world trade growth in 2017, but this is no longer the case. Trade momentum has slowed since the start of 2018 and no longer looks able to drive the same impetus across the economy as a whole.

Business surveys worldwide point to a slowdown in export orders, reflecting more sluggish momentum worldwide.

Why did we see an acceleration in 2017?

Central banks loosened monetary policy in 2016, at a time when inflation was low in most countries, bar a few exceptions such as Russia and Brazil. The Federal Reserve raised its leading rates at a very slow pace and steered its communication to ensure that investors were not spooked, especially in emerging economies.

More accommodative monetary policies kindled domestic demand in each country, spurring on economic activity and trade, and triggering broad-based momentum that was beneficial for all concerned and set the world economy on a virtuous trend.

What has changed since then?

1 – The impact of monetary policy impetus has faded and has not reappeared – we have actually witnessed the opposite trend of late. Central banks have tended to become less accommodative since the start of the year, with a tougher stance in the US since mid-April with investors realizing that the Fed was taking a more restrictive policy line. At Jackson Hole, Jay Powell clearly stated that he would take action if the economy continued to grow at a fast clip. Now that the White House has adopted highly expansionary fiscal policy, the Fed must take faster and more decisive action, marking a watershed with the Yellen era.

But Canada, the UK and even Japan have shown signs of a more stringent approach. The ECB has not yet made its move, but it has set the endpoint for QE at end-December, and slated the first rate hike some time after the summer of 2019.

The world economy is slowing and a fairly pro-cyclical monetary policy trend is emerging, with the risk that this will further aggravate the economic slowdown.

2 – European countries were unable to grow any faster, and growth at end-2017 was too fast compared to economies’ real capabilities. France’s 2.3% pace in 2017 was difficult to sustain when the economy only displays trend growth of no more than 1.3%.

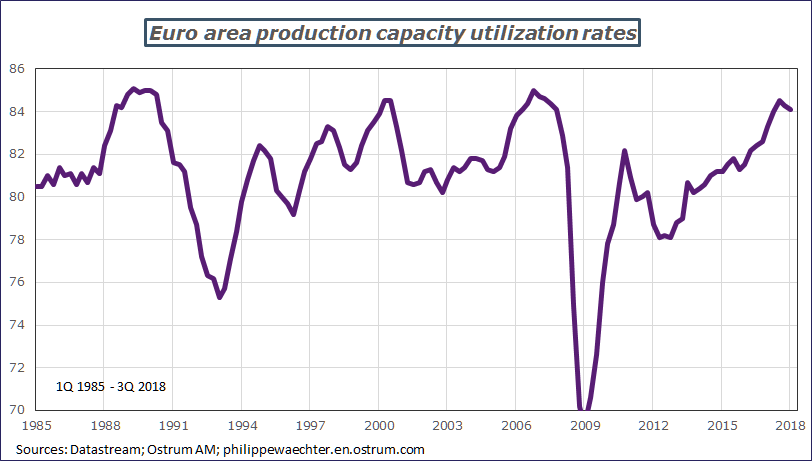

Some indicators reveal these tensions, such as French and euro area production capacity utilization rates, which hit near-record highs. Investment was inadequate both during and after the 2011 recession, thereby leading to tension when the economy did recover.

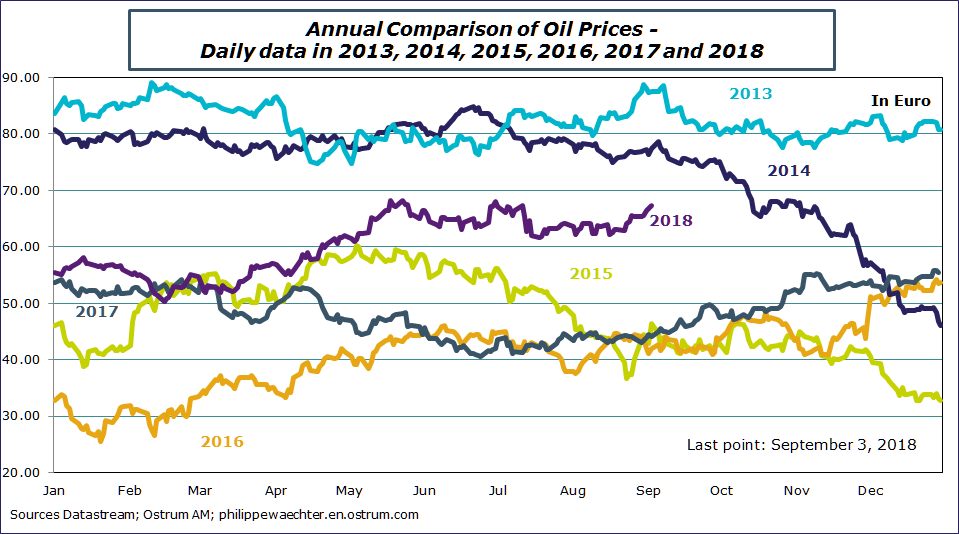

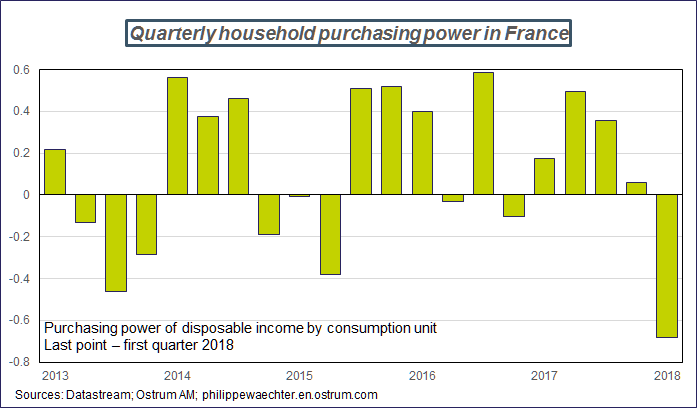

3 – Oil prices soared above $70/bbl, and inflation in developed markets followed in its wake. Prices rose by 2.3% in France in July and August, almost half of which can be attributed to the impact of energy after oil prices soared 50% in euro terms between July 2017 and July 2018, i.e. up from €42.75 to €64.40. Purchasing power took a very visible hit, as seen by holiday-makers filling up their gas tanks. Core inflation fell across the board, generally well below the 2% target mark, reflecting low wage pressure. The ECB indicated that productivity gains were low, but sufficient to cover wage increases, so this has only a small effect on pricing. Meanwhile, the US is far ahead in the economic cycle and fiscal stimulus is creating imbalances and pushing inflation up slightly.

4 – The last point worth noting here is the overall impression of a less cooperative attitude worldwide, encouraged particularly by the White House but we are also witnessing more self-serving attitudes ranging from the UK with Brexit to Italy and its new government. This creates uncertainty, which is bad for the economy: business owners are more cautious on investment when the threat of a trade war looms and makes the future less predictable.

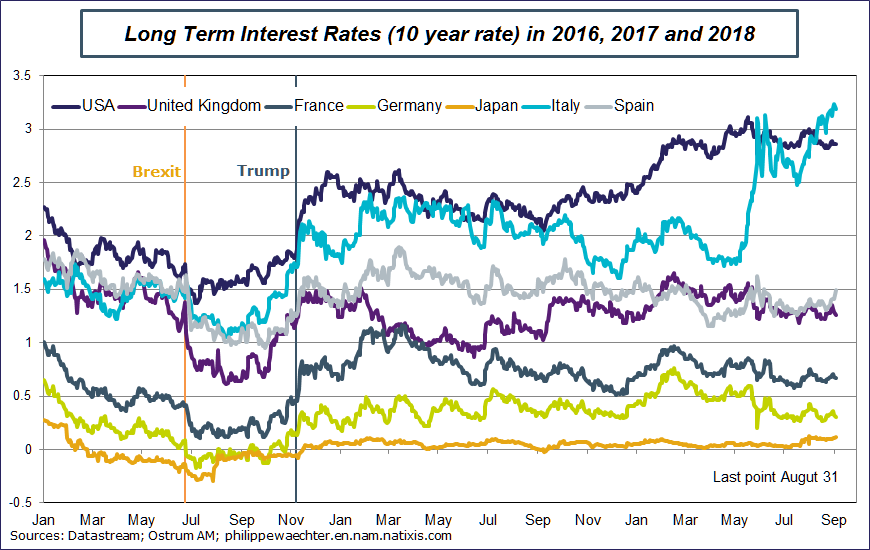

What is the latest on long-term interest rates?

Long-term interest rates remained relatively flat, and are even slightly lower in Europe than at the start of the year. There is obviously the Italian saga, with concerns as to whether the coalition government will comply with European rules, but more on that later.

Long-term rates in the US moved towards 3% after Trump implemented his fiscal policy at the start of the year and the Fed took a tighter stance to keep imbalance to a minimum. We still do not expect long-term rates to rise quickly, especially as central banks are still very actively involved in either asset purchase programs (QE) or moves to reinvest portfolio revenues. Both the Fed and the ECB are continuing in this vein and are set to keep this up well after the end of 2018.

How is the euro area doing against this backdrop?

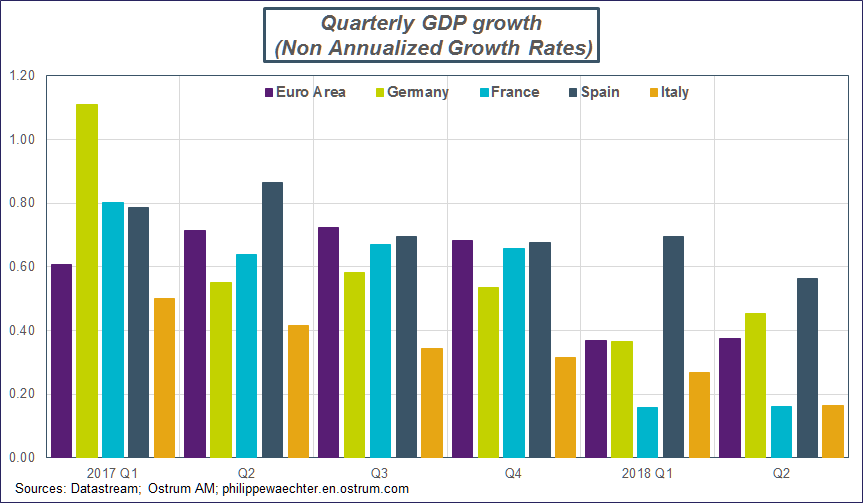

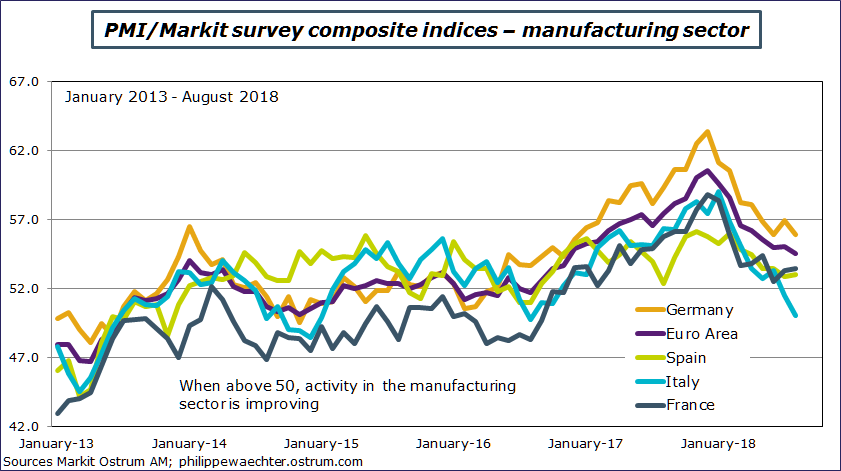

Growth is weaker in 2018: to give an illustration, quarterly growth came to an annualized average of 2.7% over the four quarters of 2017 vs. around 1.5% in the first two quarters of 2018. We are witnessing this shift in pace across all countries, even Spain, which has outstripped growth in the area’s other major economies since the 2013 recovery.

This points to both an inability to sustain the pace seen in 2017 and a dent to purchasing power from quickening inflation. Consumer spending was weaker over the first six months of 2018, with retail sales gaining 1% in volume terms on an annualized basis over the first half of the year as compared to the second half of 2017, after a 2.5% rise in 1H 2017 and 2.1% in 2H.

And how is France doing?

The situation is pretty much the same, but the slowdown is more dramatic. Average annualized quarterly growth plummeted from 2.8% across 2017 to 0.6% over the first six months of 2018, dragged down by weaker household purchasing power following on from the increase in the CSG levy for employees in the country (which contributes to social security financing), which was not fully offset by lower payroll deductions and higher inflation. In 1Q 2018, household purchasing power took its biggest hit since the recovery in 2013, so households adjusted their spending habits. Meanwhile, capital expenditure from businesses was also more unpredictable, and household investment slowed sharply.

What’s the outlook for the euro area and France?

We are now probably past the cycle peak both in France and the euro area as a whole, and this will mean a shift towards a more sustainable growth rate for the medium term. According to the OECD, French potential growth stands at close to 1.3%, so the pace will be weaker in 2018 and 2019 than 2017. We can expect 2% for the euro area in 2018 and 1.8% next year, while I think that a figure of 1.5% for France in 2018 is more feasible than the government’s 1.8% target. The expected figure for 2019 stands at around 1.4%.

Looking to the short term, August’s surveys suggest that growth peaked in late 2017. They also reveal the Italian economy’s swift slowdown, and this could be the result of the political watershed following the arrival of the new government and the uncertainty this brings. Companies will be reluctant to invest when the environment is shrouded in uncertainty…and this may just be the beginning.

Can we expect a fresh upturn?

The key question here is where the impetus could come from to set growth on a faster track. Potential growth in France probably stands at around 1.3%, and will be likely to stay close to this figure unless changes in productivity push up output on a sustainable basis and the profile of the working population changes. This suggests that real growth will move towards this potential growth mark and remain close to this trend. The economic situation in both France and the euro area shows that this shift has started, and the question we can now explore is what exactly could put a stop to this process and revive growth again.

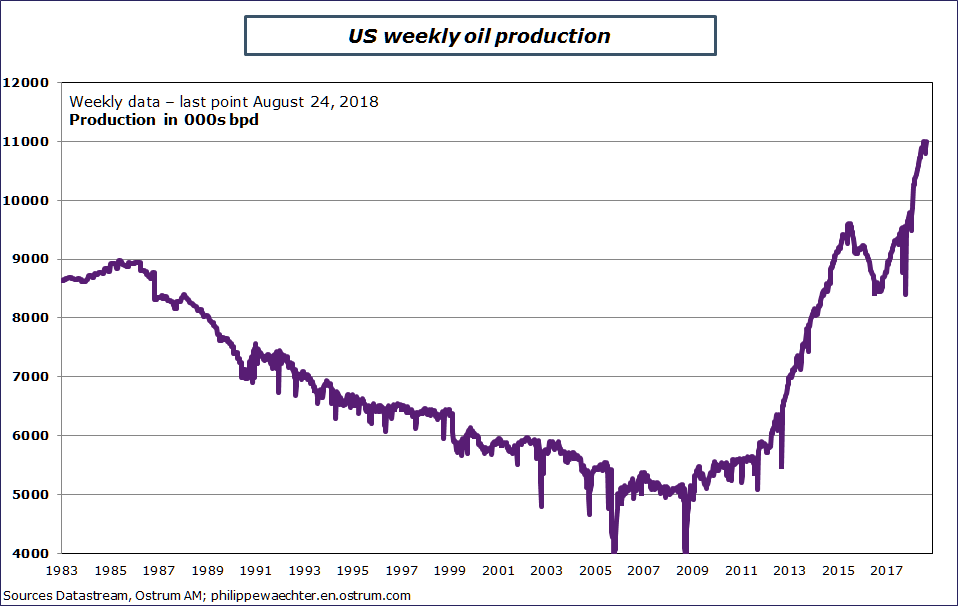

World trade will not provide a driving force, as future trends are uncertain for the reasons already mentioned, and I do not think that oil prices will collapse either. The argument that US production would keep prices low does not hold water. US production is increasing but Brent prices remains firmly around the $75/bbl mark.

Impetus will therefore need to come from domestic demand. No government wants to stage fiscal stimulus moves and the ECB remains very accommodative. Plans recently announced by the French prime minister to adjust some social expenditure and stop indexing pensions to inflation will not do much to help drive domestic demand. We will not see any impetus from economic policy either, and innovation does not provide the inherent momentum required to trigger a natural upturn. So growth is set to move towards its long-term trend. The role of economic policy and particularly the infamous structural reforms is to drive up trend growth but this takes time and we are moving out of the short-term and into the structural.

And what about the ECB?

Before the summer this year, the ECB announced that it would half its asset purchase program in October and bring QE to a complete halt in December, and also noted that the first rate hike would very probably take place after the summer of 2019.

What about the US economy?

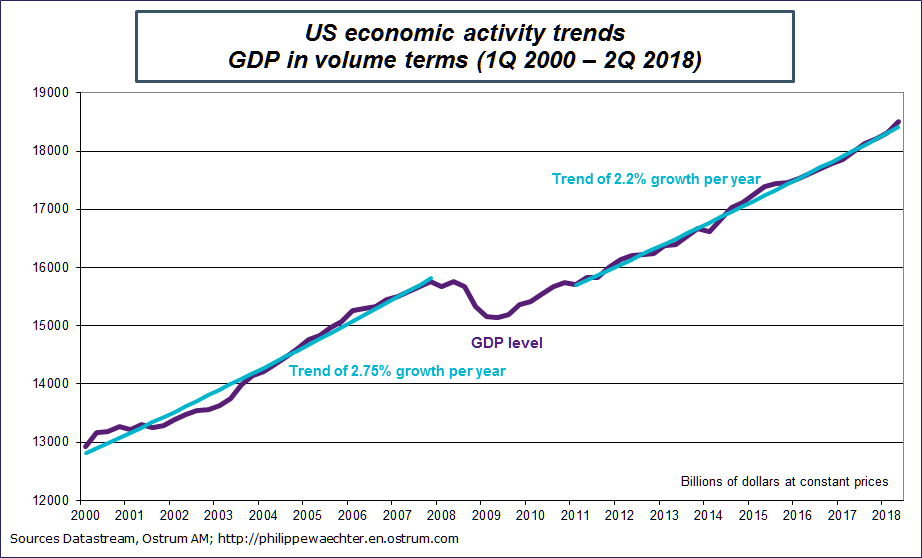

The US economy is doing fairly well. Growth picked up to 4.2% on an annualized basis, and looking at the same comparison we made for the euro area and France, average annualized quarterly growth came to 2.5% in 2017 and then 3.2% on average over the first few months of 2018. This reflects both the continuation of the previous trend and the hefty impact of tax cuts and increased state spending. Fiscal stimulus is set to make for a public deficit of close to 6% of GDP, which is steep.

Other points worth noting in the US

This current economic situation forces the Fed to tighten the thumbscrews and it will hike its leading interest rate four times this year, with September’s and December’s moves still to come.

The corporate tax cut program was intended to encourage massive investment programs with the aim of driving stronger growth in the future, but companies actually used the windfall to buy back shares and buoyant showings on the US market are largely a result of this.

The real estate market has been losing steam. Rising mortgage rates are denting household investment and this market is raising doubts on the strength of the US economic cycle over the months ahead.

Meanwhile, the Fed is pushing the yield curve flatter, which should also dent the economy by hitting short-term financing, especially for mortgage brokers.

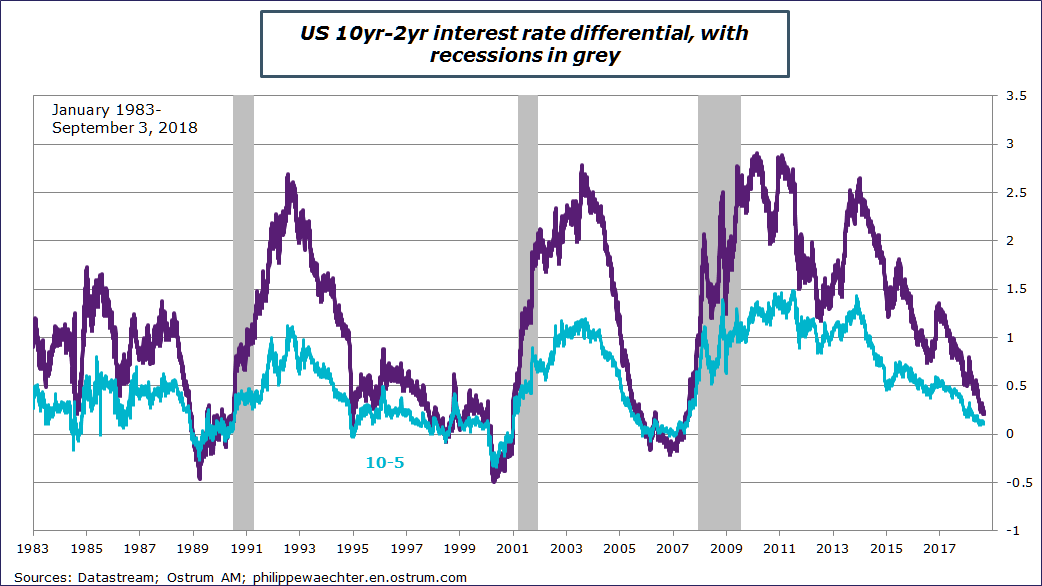

There is a lot of talk about the US yield curve, what’s the score?

The yield curve has flattened considerably over recent months due to the rise in short-term interest rates, which reflect expectations of the Fed’s moves over the months ahead. The long end of the curve has not changed significantly as inflation projections have not taken an upturn on the one hand, while on the other hand, future monetary policy will not have the same impact on interest rates as compared with strategies in the past, due to lower potential growth and the Fed’s continued strategy of buying US Treasuries when reinvesting its portfolio revenues.

The million-dollar question is what the effects of this flattening yield curve will be – and just how will the move into negative territory translate. Past experience shows that there is ALWAYS a severe economic slowdown with an 18-month lag – i.e. a recession – and the trend is particularly marked when the curve flattens primarily as a result of rising short-term rates, or in other words intervention from the central banks.

Every time a problematic issue emerges, many rush to claim that it’s different this time, but this time will not be different. Monetary policy will hit the vast numbers of large brokers who currently use short-term refinancing on the real estate market, with a major impact.

That long-term rates are not higher is very telling and reflects unambitious economic projections. Meanwhile, the perception that the Fed is buying a lot admittedly changes the market’s profile, but it is also worth remembering that Fed chair Bernanke reflected in 2005 that long-run rates were not a reliable signal due to the famous saving glut and that there was an artificial aspect involved. Yet this did not stop the economy diving into recession a year and a half after the yield curve moved into negative territory.

We can therefore potentially envisage that the country could fall into a recession in 2020 in light of US monetary policy.

The Fed may well have the wherewithal to manage the situation when the time comes, but there would be a problem elsewhere as the same cannot be said of the ECB. If we believe Mario Draghi’s statements, it will only have hiked its key rate once to 0.25% by the end of 2019, and this will not be enough to address any knock-on effects from the US.

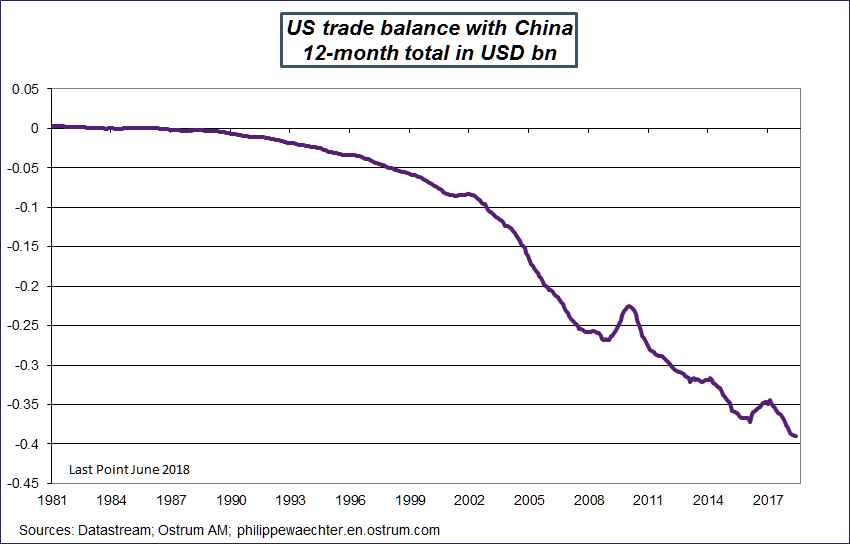

The White House has been implementing massive tariff policy changes since the Spring and an agreement has just been signed with Mexico – what should we make of this?

On January 20, 2017, the White House challenged the free trade agreement rules with Mexico and Canada, and also put pressure on the two countries by targeting them in the tariff hikes on steel and aluminum it implemented in the Spring. An agreement has just been reached with Mexico and talks are under way with Canada.

A first point worth noting is that the White House here seems to be leaning more towards two bilateral agreements rather than one overall agreement, and this fits more neatly with Trump’s usual approach, as he tends to look for bilateral rather than multilateral agreements.

The agreement with Mexico focuses on the automotive industry with more stringent rules than NAFTA: rules of origin on parts used in manufacturing vehicles as a % of the total produced will be more restrictive in order to qualify for zero tariffs, while in Mexico, 45% of staff involved in producing the vehicles must have an hourly wage of 16 dollars or more. These requirements will push up prices for US cars and it may be in carmakers’ best interests to bypass the agreement, even if it means paying higher border tariffs, but which still only amount to 2.5%. It will be up to carmakers to weigh up the benefits.

However, this may well only be a short-term solution as the government will swiftly hike automotive tariffs. This agreement is actually the trigger that is needed to push import tariffs on vehicles up to 25%. Requirements are tough, but there are good reasons to bypass them too, and this provides an ideal opportunity for the White House to do what it has intended from the outset, while being perceived as not entirely responsible for the situation.

Meanwhile, the first trade measures on China have been implemented, but it is still too early to say whether US tariffs are having a major impact or not. The US deficit is still vast, so we can likely expect the US administration to beef up its trade restrictions on the country.

And what about China?

China is hit by the impact of the White House’s protectionist moves and has eased monetary policy to offset the potential negative effects of US actions. Tariff tit-for-tat is a no-win game for all concerned and the US is beginning to suffer the cost with higher prices for some goods.

And Brexit?

The situation is at a stalemate for the moment and we are hearing increasing talk of a no-deal scenario, which would mean no European rules in the UK and very bad news for the country’s growth. If a deal is not reached, European rules could not apply in the country, especially for trade and communications, and new rules would need to be negotiated. This would take a long time, yet this previously unlikely scenario is becoming less unlikely.

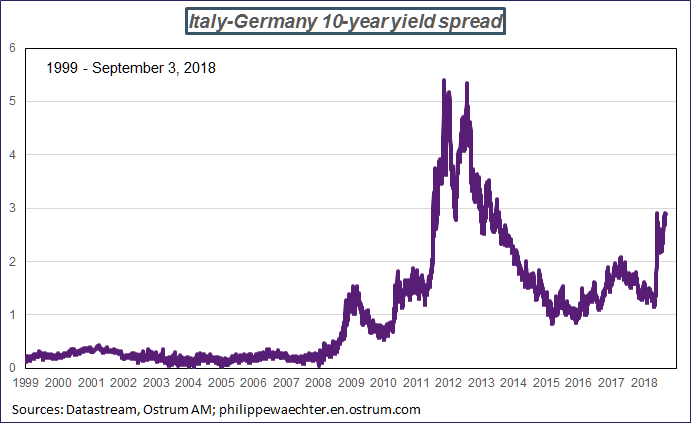

What’s going on in Italy?

Italy will not be leaving the euro area in the next few months – it would cost too much – so this is not the root of market concerns. But yet investors outside Italy are exiting the Italian debt market, with around 34 billion in net outflows from the country in June and July according to the ECB. This is a hefty amount and reflects concerns by non-resident investors on what might lie ahead for the country, with rising yields on Italian debt testifying to their uncertainty.

Ratings agencies are set to look into the Italian situation and a downgrade could drain liquidity from the Italian bond market. The situation is particularly problematic as the government is not keen to conscientiously comply with European budget rules.

This is a simple yet tricky matter – if the Italian government implements its election trail promises, the public deficit will increase well beyond the infamous 3% threshold. (Countries may exceed the threshold in the event of an economic shock and from a macroeconomic standpoint it is actually more effective to let the deficit increase, but in the current Italian example, overshooting the threshold reflects a very deliberate approach, setting it very clearly apart from the post-Lehman crisis period in 2008 or the sovereign debt crisis in 2011-2012.) Italy’s rating would invariably end up being downgraded, and Fitch has already lowered its rating outlook to negative, although it maintained its BBB rating. These factors would combine to put international investors off investing in Italian debt, which would make it harder for the country to finance its economy as there have traditionally been high numbers of non-resident Italian debt investors.

After a while, the Italian government would have difficulty gaining funding and would have to request help from the European institutions e.g. the ECB and the ESM. But this would mean the Italian government would have to adopt a more orthodox approach.

The situation raises two questions:

How high would interest rates have to go for the government to request help and when is this likely to happen? Spreads are already very wide, but still a far cry from figures during the sovereign debt crisis in the euro area.

The other question involves the way institutions work. In a European context, budget rules are generally adopted then all countries follow them even if this can take some time. Few countries immediately adjust their budget situation but they all endeavor to comply with the rules as a whole, and adopt a cooperative attitude. Italy does not want to take this cooperative path at this point and this changes the rules of the game. We will be interested to see the reaction from the European Commission and the ECB on these matters, as well as from the various other governments. There is little scope for applying pressure ahead of time as all countries generally take a cooperative stance, but not the Italian government.

Are emerging markets still in crisis?

Yes they are. There have been three stages for emerging markets since mid-April and the perception of sustainably tighter US monetary policy: there was a surge in the dollar and capital flight out of emerging markets and into the US; liquidity on these markets dwindled, prompting investors to withdraw or steer clear; long-term rates for a number of emerging countries took a very definite upsurge. This has meant a negative shock for each emerging economy and a source of weakness for the global outlook as a whole.

How does Turkey come into it?

Turkey has extensive dollar-denominated debt, just like Argentina, South Africa and a few other countries. Currency adjustments for these countries were a bit more significant than for those that had little or no dollar-denominated debt. The situation became even more fraught when Turkey came to blows with the US on the issue of the US pastor held in the country. Severe pressure from the US pushed down the Turkish lira, creating a worrying situation on this market for the long term as currency depreciation is set to further push up inflation and dent the economy.

The only solution would be to control the capital markets and take the steps required to change investors’ expectations before reopening this market. The Erdogan government does not want to tackle the issue and the situation will not solve itself, especially after Turkish banks were hit by ratings agency downgrades.

What’s been happening in Argentina?

Argentina has been subject to the same mechanism as Turkey, except that it will need to roll over hefty external debt out to end 2019 (between USD50bn and USD80bn according to estimates). The country could rein in its spending, but President Macri wants to run for office again next year, so it would be difficult to enter the presidential race after taking measures that would push the country into recession. So Argentina appealed to the IMF, which took its time and asked Argentina to keep its 30% inflation in check and adopt more restrictive fiscal policy to dampen internal demand and curb its dependency on external support. Macri’s frustration last week at the IMF’s failure to provide a clear reaction pushed the peso down even further. During the night of September 3-4, the government finally adopted the strict measures required to secure IMF support, but the question now is whether these measures will translate into long-term changes.

What about Venezuela?

Venezuela is in the throes of hyperinflation. Oil production is plummeting and dragging down the country’s income in its wake. The government has been frantically printing money to make up for this, but Venezuelans have now realized that their currency is worthless and have been trying to get rid of it as quickly as possible. The decline in the currency’s intrinsic value lies at the heart of this hyperinflation and steps taken since August 15 will only serve to fuel this trend. The government has taken no pledges to change its approach on either monetary or economic policy. The situation for the Venezuelan people will continue to deteriorate and they will continue to flee their country in greater numbers.

Is there a danger that this situation will spread?

There are two key aspects to bear in mind:

1 – We have seen a shock on emerging economies, which is bad news for everyone, but this has not led to a breach in “average” economic performances as the economy remains buoyant in spite of it all, particularly in Asia, which is powered by Chinese growth. This buoyant economic activity curbs the risk of knock-on effects, especially for countries that do not have an external deficit.

We would revisit the matter in the event of a negative shock on economic activity as expectations would then obviously change significantly.

2 – The countries that are struggling the most are hit both by their dollar-denominated debt but also by some very specific individual factors, so the risk of contagion looks lows.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog