The British vote validates the choice of Brexit and the exit from the European Union on January 31, 2020. Boris Johnson is free to define his strategy.

Boris Johnson’s huge victory in the British elections leaves no doubt that the British will leave the European Union on January 31. This conservative tidal wave is a Brexit referendum and the result of June 23, 2016 is largely confirmed.

The Labor Party has been shattered, its worst result since 1935, and the Liberals who campaigned for the Remain score poorly and will not weigh in the new parliament.

The elections eliminate the uncertainty on this point, there will be no further postponement and February 1, the United Kingdom will be outside the European Union.

The political risk emerging from these elections is the situation in Scotland. The SNP, the pro-independence party with 55 seats, has a very strong position. He wants Scotland to stay in the EU and indeed a Scottish referendum on this issue can not be ruled out in the coming months.

What are the next deadlines?

The first point to emphasize is that Boris Johnson campaigned for Brexit and he won. This means that the uncertainty that has been perceived in parliament since the referendum has been lifted. There will no longer be the procrastination observed since that date. As the opposition is now very weak, there will be no alternative.

The next step is the return to parliament on December 17 and the appointment of Boris Johnson as Prime Minister. Next, parliamentarians will have to vote on the Withdrawal Agreement Bill on January 31.

The next stage, which Boris Johnson wants to confine to the year 2020, will be the negotiation of the trade agreement framework with the EU. This framework should define the UK’s relations with the EU in the medium and long term.

On this point, Boris Johnson will need to adopt a clearer language than what he has indicated so far.

Indeed, the British have two possibilities.

Either they want to stay close to the European Union with access to the single market but then they will have to accept losing part of their sovereignty over taxation, the job market, the environment while respecting the 4 freedoms of movement (people, capital, goods and services).

Or they want to define a different framework, for example with attractive taxation and less restrictive regulations than those of the EU (the famous Singapore model).

Boris Johnson and the conservatives will have to choose between the two options. So far, Boris Johnson has decided not to choose by wishing to have autonomous rules while maintaining access to the single market. It was the easiest strategy to win the elections and convince citizens. It will be different in discussions with Brussels.

However, a choice will have to be made quickly because BoJo wants negotiations on this trade framework to be completed at the end of 2020. If it takes longer than expected, the British can request a 2 year postponement before July 1.

On the economic front, the exit of the British reduces part of the uncertainty surrounding the economy. This was reflected overnight in the appreciation of the British pound around 1.35 against the dollar.

Beyond these short-term movements that we will probably also see on the equity markets, the question of the positioning of the United Kingdom vis-à-vis the rest of the world remains open. It will not be resolved spontaneously by these elections since the the context in which the UK economy will evolve is not yet defined.

Economic signals are currently showing a precarious situation and one can not imagine that, in the coming weeks or in the coming months, investors will rush to the British Isles. The mistrust that has been observed since the referendum will not be spontaneously lifted and the cost already suffered will not be quickly absorbed. Boris Johnson has promised a recovery plan, but we have to wait to see the details before changing our opinion on the British risk. In the short term, the risk is a further downturn in the economy in line with the pace of the rest of the world.

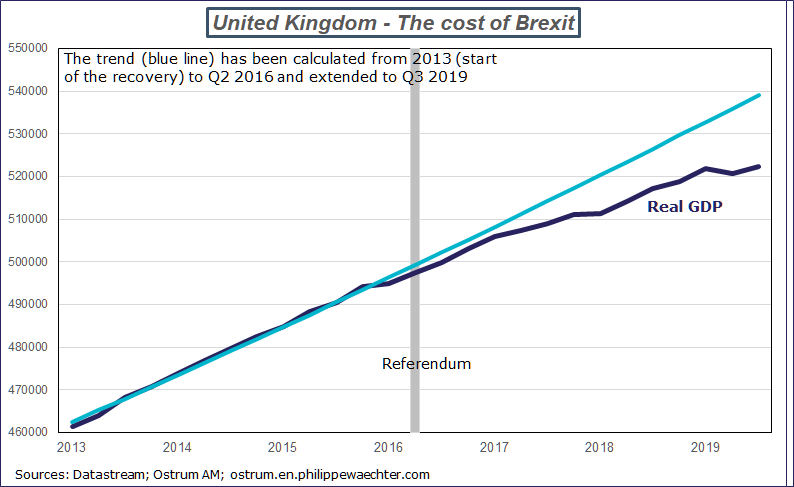

This graph shows real GDP in level since the start of the recovery of the British economy in 2013. I calculated a trend (in blue on the graph) over the period 2013 until Q2 2016, date of the referendum, and I extended it until the third quarter of 2019 (last data available). If Brexit was the source of the divergence between GDP and its pre-referendum trend, the cost of this for the British economy has so far been 3.1%. Following the trend, GDP would be 3.1% higher.