Momentum on the labor market in France

warrants greater consideration as it can appear counter-intuitive at first

glance. The unemployment rate stood at 7% in the second quarter of 2020, hitting

its lowest point since the first quarter of 2008, while GDP plunged 13.8% over

the same period. Meanwhile, employment only dipped by 0.6% over the same spring

months. There is nothing mysterious or ominous about these trends, but rather

it is important to consider why these labor market indicators that are the

subject to much scrutiny have seen such a particular trend at a time when the

French economy has faced an unprecedented contraction, unseen in peacetime.

There are two main points to look at: firstly, the structure of economic policy

and its impact on job trends, and secondly the methodology for quarterly

surveys.

1- Structure underpinning economic policy

Economic policy has had to tackle two fresh challenges as a result of the Covid-19 crisis: the first issue at hand was to stop the spread of the disease by cutting down human contact and interaction as much as possible, this was the lockdown phase; secondly, it had to curb the effects of the economic standstill on jobs.

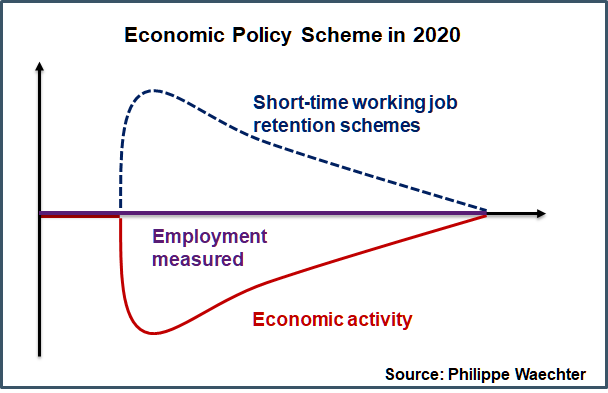

In the short term, jobs and activity follow a similar trend, so taking the risk of suffering a 10% drop in economic activity also involves the risk of seeing jobs plummet by 10%. However, the government’s moves to roll out short-time working job retention schemes to avoid a disastrous social impact help ward off this catastrophe. The increase in this state-funded job retention program must offset the decrease in work triggered by the temporary drop in economic activity, and the surge in this short-time working job retention system is the mirror reflection of the drop in jobs resulting from the decline in economic activity.

If the situation goes as planned, there is no effect on the effective job rate as staff benefiting from the short-time working job retention system keep their jobs: the goal behind this set-up is to be able to act very swiftly when economic activity takes an upturn again, and first and foremost to avoid redundancy costs when activity dips, along with recruitment costs when it recovers (it is worth noting that costs are not merely financial).

In this scenario, job numbers as shown by the purple line on the chart are stable as the decline in economic activity is offset by the increase in the job retention program.

This was not the case, as in the first quarter of the year the roll-out of short-time working job retention programs did not perfectly coincide with the start of the lockdown period, and also as economic momentum does not equate to the ideal configuration outlined point by point. Despite efforts, some companies did close and some made their staff redundant. However, this scenario still provides a good explanation for the small drop in jobs in the second quarter (click here for more details, text in French only)

2 – A question of methodology

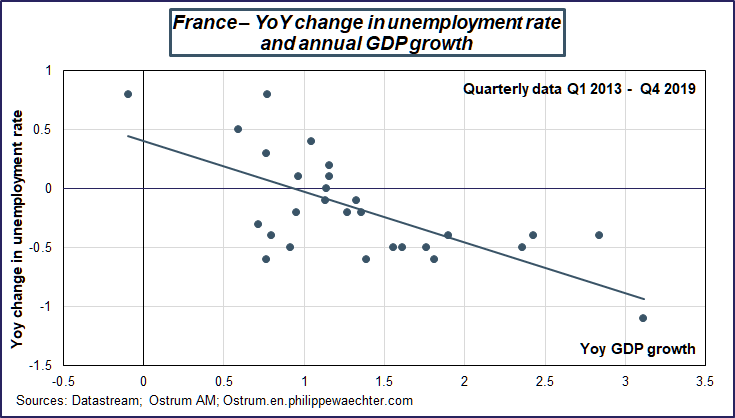

Jobless number trends usually follow economic activity showings. On the chart we can see that activity measured on the horizontal axis and unemployment on the vertical axis display similar trends i.e. when the pace of economic growth surges, unemployment decreases and vice versa.

Thus the 5.7% decline in activity YoY in the first quarter of 2020 and the 19% plunge in 2Q should have triggered a massive surge in jobless numbers, but this was not the case as the unemployment rate dipped by 0.3% over the first three months of the year, while the figure saw a drop of 0.7% to 7% over the spring months in mainland France.

There are technical factors behind this, which I explain here (text in French only.

Job-seekers must meet certain conditions to be considered as unemployed as defined by the International Labour Office i.e. they must be without employment, have been actively looking for a job over the past four weeks and be available for employment within two weeks.

However, these conditions cannot apply when the economy has been put into lockdown. It makes no sense to talk about active job-seeking when entire portions of the economy have ground to a halt, while being available for employment within two weeks cannot be applicable either when the economy is not operating, so the number of job-seekers plummeted during the lockdown period.

During this highly unusual period, French statistical office INSEE thus calculated that the unemployment rate fell to 5% in April. At the end of lockdown, behavior then normalized and trends became more consistent with figures usually witnessed.

However, lockdown lasted for almost a month and a half in the second quarter of the year, so while trends got back to normal after lockdown, the average figure was affected by the first six weeks of the quarter. The jobless rate thus fell to 7% on average over the three spring months.

Based on weekly figures used by INSEE, the unemployment rate came out at 8.1% in June, while on a monthly basis, unemployed figures followed the same pace as all monthly data, with a sharp plunge in April then a rebound. The severe drop here is a result of the methodology mentioned above.

Labor market has only partly adjusted

and major uncertainties remain.

1 – In the scenario outlined above, the underlying assumption is that economic

activity will eventually resume its previous trends and so jobs will follow

this same path. But this is probably excessive as the economy may not get back

to its trend as quickly as expected. In this situation, weaker macroeconomic trends

than expected would trigger a downward adjustment on the labor market and the equilibrium

point for jobs would be lower than it would have been in the base scenario.

If this shortfall is a result of a lack of economic momentum due to business

closures or some industries’ failure to resume growth as the economy has

changed, then the short-time working job retention process no longer applies

and jobs decrease.

2 – In some sectors, economic activity is still directly hampered by the

restrictive effects of the pandemic, and the government has converted the job

retention program into a long-term short-time working scheme for these

industries to enable them to maintain jobs in these sectors by providing

funding for their employees. In the longer term, we cannot rule out the possibility

of some businesses going under if trend growth remains below the pre-crisis

pace.

3 – So two key questions must be addressed: how can the labor market situation be

managed when the economy changes and the buoyant sectors are no longer the same?

However, this standard cycle set-up also goes alongside an unprecedented

negative shock on activity in the current situation, and this makes the labor

market’s adjustment more challenging. The more robust sectors will be set

against industries that have been hard hit by the shock from the current health

crisis: this vast differential is unusual and leads to distortions that hamper

job market momentum. The other main issue is the persistence of the damaging

effects on business sectors that are still dependent on the health crisis. This

is a long-term aspect and does not help the labor market get back to normal.

Thus labor market trends will be the key to expansion over the months ahead, which will help get back to a more comfortable situation for the long term. If consumers are reassured on the labor market’s showings, then they may reduce the reserve of savings they have built up and the economy could become more robust again.