The ECB, after Christine Lagarde’s remarks at the February 3 press conference, is following in the footsteps of the Fed.

Like the US central bank, the ECB has changed its mind about inflation, eliminating its temporary nature. It then let it be known that it could raise its interest rates even if it is still a distant horizon (Lagarde alludes to this and the governor of the central bank of the Netherlands speaks of a rise in the last quarter of this year in an interview with the Financial Times this weekend).

In September 2021, the Fed had indicated the possibility of raising its benchmark interest rate once at the end of 2022 and in early December Jay Powell, the chairman of the Fed, withdrew the temporary nature of the rise in inflation.

In both cases, the change in tone of the central bank is radical and if the increase in interest rates seems distant and announced by the most radical central bankers, therefore necessarily excessive, the information nevertheless becomes public. The attitude of the governor of the central bank of the Netherlands is instructive, he is no longer in the usual criticism of the laxity of monetary policy, he gives information on what it could do. It’s very different.

This information from central banks is necessary to allow investors to adapt their expectations. If the announcement is too brutal (February 4, 1994 for those who remember, the financial markets’ adjustment was harsh) the impact can be dramatic.

* * *

In March, the ECB will announce its new forecasts with most certainly a higher inflation rate in 2022 and 2023 than that forecast in December. It could then, like the Fed before it, accelerate the tightening of its monetary policy since it will then have completed its specific program on the pandemic (the PEPP will end in March).

The Fed first accelerated its announcements in December and moved them even closer in time at its January 25-26 meeting. It will start a more restrictive monetary policy in March with the desire to go further from the start of the summer with a reduction in the size of its balance sheet.

The ECB will not follow the Fed point by point because the profile of inflation and wages are frankly not alike. However, if the ECB followed the same dynamic, the same tempo, then it could raise its benchmark interest rate at the July 21 meeting.

It is important to have this pattern in mind. However, the questions asked are not always the same.

* * *

In addition to the level of inflation, the common problem of Americans and Europeans is energy. In the Euro zone, more than half of inflation is explained by energy and it is a third in the United States.

On this point, two types of questions arise.

The first is the inability of central bankers to weigh on the price of energy. Intervening would be counterproductive if the rise in energy prices is not sustainable and the observed acceleration is not long-lasting.

However, and this is the second question, if the contribution of energy is high over time, the outlook changes. A permanent rise in the price of energy is a loss of purchasing power and necessarily a source of wage demands. When the British, in April, will see that their electricity bill has increased by 54% (announcement by the government on February 3) they will probably have demands to offset part of it with wage increases.

The situation will be of the same type in the Euro zone because the price of electricity has increased everywhere. If the French government pools this shock, this is not the case for all governments. Losses in purchasing power are to be expected. The more the rise in energy prices will reduce purchasing power over time, the stronger the demands will be.

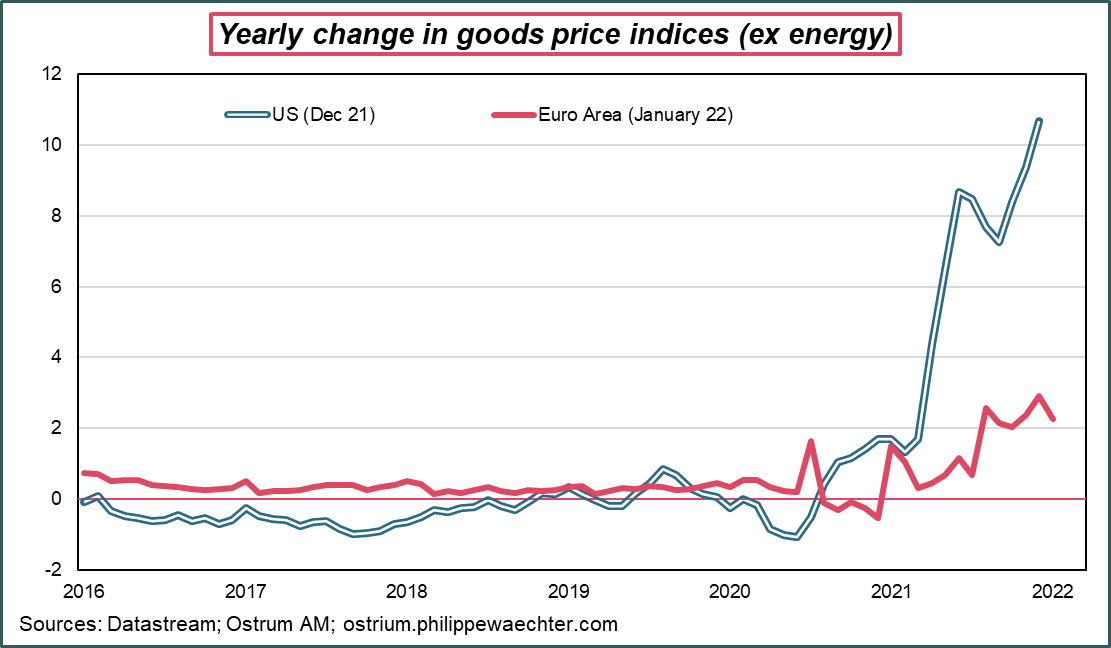

This mechanism does not work so far and wages in the Euro zone do not increase at the same speed as in the US. In the management of monetary policy this is a major difference. In compliance with the objective of price stability, the issue of wage indexation is essential and the central bank cannot facilitate the implementation of such a dynamic.

* * *

What should the central bank do in this situation?

Should it take the risk of accepting an inflation bonus built into wages with a high probability of seeing this phenomenon continue over time? If it opens the possibility for wages to adjust upwards, then the pace of the prices of goods in particular could approach that observed in the US. What the ECB does not want because of its mandate.

However, if it gets tough too quickly, the restrictive effect of monetary policy will fall directly on economic activity. This could influence demand and activity and ultimately the price of energy, but is this the desired and desirable course?

This is why the data available at the ECB’s March meeting will be essential to properly distinguish the evolution of the components of inflation. These data will then feed into the ECB’s projections.

Either inflation continues and the ECB must tend to become restrictive, or inflation has erased enough purchasing power to weigh on demand and price trends, the ECB could then wait.

* * *

Two questions remain unanswered:

The first is that of the price of energy. Price dynamics have been disrupted since last summer, particularly for gas and electricity. Beyond the immediate future, this will be a key element of the structural adjustment that the world economy will have to make as part of the energy transition.

The second is that of the experience of the ECB in this type of situation. In July 2008, the ECB was criticized for raising interest rates which dried up liquidity when the price of oil was at 145 dollars and underlying inflation was close to 2%.

In April and July 2011, the rise in interest rates accelerated the recession in the euro zone at a time when budgetary policies were becoming frankly restrictive.

This means that the right policy mix would be a rather restrictive monetary policy and an always accommodating fiscal policy. The Euro zone must not lose the advantages of its exit from the health crisis.