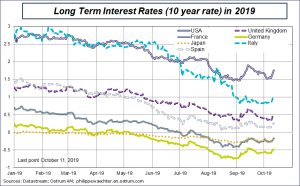

Monetary policy has been at the heart of recent market trends once more. The minutes from the US Federal Reserve’s meeting on September 17 and 18 as well as from the ECB meeting on September 12 reveal that central bankers’ views can be fairly diverse. In other news, the Fed announced that it would be buying T-bills to tackle liquidity risk, such as the situation witnessed after September 17 on the US money market. These various factors led to uncertainty and more divergent projections for the financial markets, with interest rates surging as a result.

In the US, the Fed decided to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 25bps at its September 18 meeting, from a range of 2.00-2.25% to a range of 1.75-2.00%. The dot plot also points to a further likely cut in December.

However, James Bullard, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, was in favor of a 50bps cut to help growth take an uptick more quickly and promote a more rapid return of inflation. At the same time, Esther George, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, wanted to keep interest rates steady as she believes that greater monetary accommodation is not yet necessary given the current state of the economy. Meanwhile, Eric Rosengren, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, believes that monetary policy is already sufficiently accommodative judging by the pace of the economy, and that further moves are not necessary. The various central bankers in the US do not share the same view of how the Fed should act, and this could lead to uncertainty for investors.

In the euro area, the ECB’s decisions at its September 12 meeting did not all meet with the same enthusiasm. The decision on banks’ role in financing the real economy via the TLTRO program was approved easily – it is vital to facilitate funding for the economy to ensure strong renewed growth.

The two-tier system for reserve remuneration was also agreed, and banks’ reserves will no longer be entirely subject to the negative deposit facility rate, which was cut to -0.5%. As much as six times banks’ mandatory reserves may now be exempt from the deposit facility rate, and this means a hefty transfer of financing from the Eurosystem to the banking system. The aim here is to safeguard a robust banking system to ensure that monetary policy moves feed through to the real economy. However, there were discussions as to whether these measures were compatible with an easing in the terms of the TLTRO program.

There was even more dissent on the issue of forward guidance. Interest rate and quantitative easing measures will be maintained until inflation converges to a level sufficiently close to, but below, 2% on a structural basis. Should the bank have kept this measure time-specific or should it make moves dependent on achieving the inflation target? Was this the focus for debates?

The most hotly debated issue was the resumption in the quantitative easing program. The ECB will resume its asset purchase program on November 1 at a pace of €20bn per month. This will round out reinvestment of principal payments from maturing securities in the ECB’s portfolio of around €10bn. The new-look QE program is expected to end shortly before the ECB starts raising its key interest rates, while reinvestment will continue past the date that the Governing Council starts raising key ECB interest rates.

There are questions as to the need for this move, although the ECB believes that it is necessary and that previous programs had promoted both growth and inflation. However, some critics of this policy feel that it is not necessary, while other opponents think that QE is not the right policy instrument in this situation. Interest rates surged in the euro area as a result of these various aspects, and with the Bundesbank and the Bank of France opposed to this move, investors felt that there may be some change to come. However, the governor of the Bank of France has since stated that they must now turn the page.

The important point here is that Christine Lagarde’s hands are now tied and she must follow the ECB’s decisions.

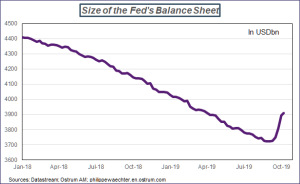

In the US, the Fed decided to inject massive liquidity into the money market. The US money market came under pressure on September 17, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York intervened over the space of several days to inject significant cash into the system to tackle this liquidity risk, as shown by the chart on the size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

The Fed is also set to intervene by buying $60bn in T-bills between mid-October and mid-November and will then adjust this amount depending on market conditions until the second quarter of 2020. It will also continue its overnight repo operation until January 2020 to support the market’s adjustment.

The Fed does not want to call this program quantitative easing, but rather it is a way to provide the liquidity that the money market needs to avoid a shock on financial assets having any knock-on effect. This is a vital point: the central banks – and the Fed in particular – want to make sure they can address any potential financial shock very quickly and avoid any danger of it spreading. This can be seen as a transitional phase as the Fed has only set out plans until next spring, but it can also be viewed as an indication of fears that the situation could get out of hand, so every effort must be made to avoid any negative impact for the markets and the economy.

Indicators issued during week of October 7

We particularly note fairly robust industrial production figures in the euro area, apart from France where industrial output plummeted 0.9% and manufacturing output dropped 0.8% in August. Sound figures from Germany and Spain drove a 0.4% increase in production for the euro area as a whole in August.

The US labor market continues to adjust. Despite a dip in jobless numbers to hit a low of 3.5% in September, survey data show that momentum on job openings is much less robust. The labor market remains solid, but is not as buoyant as before, and this is also reflected in monthly figures on new jobs created, with both private sector and total job creations over the month at their lowest since 2010.

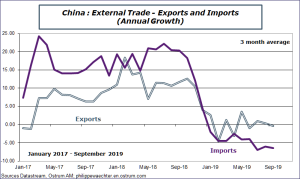

Looking across the globe, Chinese external trade continued to deteriorate, with exports contracting slightly and imports continuing to decline hastily. The Chinese government does not want to embark on aggressive economic stimulus: the economy is not undergoing a shock, but rather domestic demand is sluggish, as reflected by investment as well as imports. We also note the 22% collapse in exports to the US in September yoy, and this downtrend is gathering speed after a 16% drop in August. China is shifting its external trade to make it less dependent on the US, but this change could turn out to be tricky, so a more ambitious domestic policy may be needed to offset this external shock. US-China trade talks are making no progress, despite what the White House says.

Three key points to watch over the week ahead

The first is an ongoing but crucial issue – Brexit. The European summit on October 17 and 18 must address this issue and settle the final position on the matter. BoJo’s proposals for dealing with the Irish border issue are still not convincing, so if a deal is not reached at the summit the Prime Minister will have to ask for an extension, unless the 27 push the UK out of the bloc with no deal, but that seems unlikely.

The second major piece of news this week will be the US Fed’s Beige Book. These figures may clear up Esther George’s and Eric Rosengren’s doubts on the need for the Fed to cut interest rates.

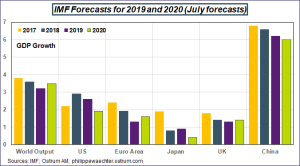

The third event is the World Bank and IMF annual meetings. The IMF will give its outlook on the world economy and issue fresh projections. July’s figures indicated that we had hit the cycle peak in 2017, with a low in 2019 to be followed by a recovery in 2020, mainly on the back of a more robust economy and a rebound for emerging markets. However, doubts may emerge on this trend to an improvement.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. The good news is that Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer have been awarded the Nobel prize for economics for their work on tackling poverty using ground-breaking methodology. Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee published the book “Poor economics: a radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty”, available in paperback.

So why not read this enjoyable and interesting book to find out more.

Have a good week!

This column was posted in French on Monday the 14th (See here)