Twenty days after the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the risk of inflation takes precedence over the risk of slowing activity in the perception of investors.

At her press conference, Christine Lagarde stressed the importance of the inflationary risk after the upward movement of commodity prices and the disruptions in the dynamics of the production process. Jay Powell also, at the same time, had a rather voluntarist statement about the more restrictive orientation of American monetary policy.

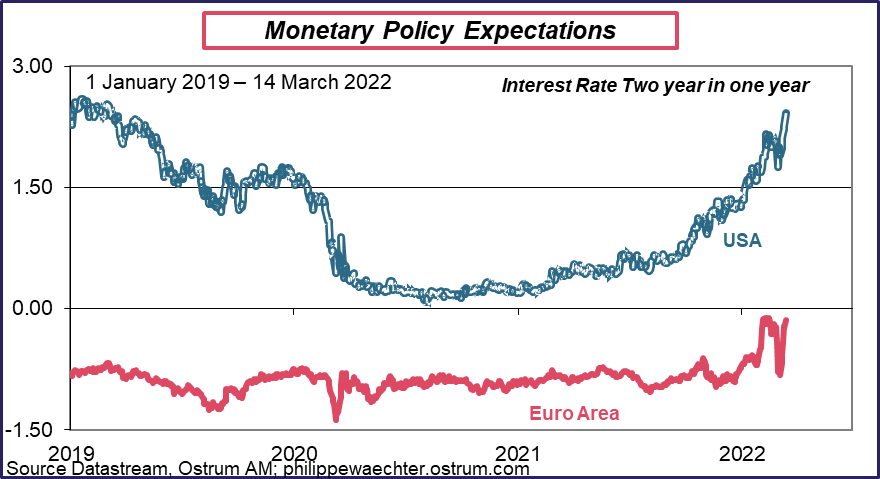

Investors have followed suit. Expectations about the evolution of monetary policy have clearly increased and the decline that followed Ukraine’s aggression has passed. The two-year rate in one year, a good indicator of monetary policy expectations, is up sharply. In the Eurozone, the 2-year rate in 1 year has returned to its pre-crisis level.

Christine Lagarde had indicated at the beginning of February that the ECB was not ruling out the possibility of raising rates. On 10 March, in the same way, the President of the ECB created a reversal of the trend. In the USA, where the upward trend has been more pronounced for a longer time, the 2-year-rate in 1 year is at its highest since early 2019, well above the level seen before the crisis in Ukraine.

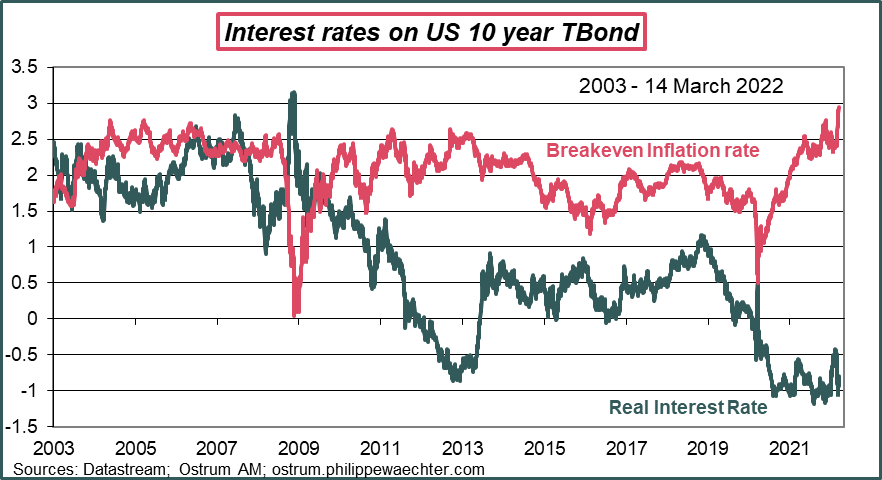

At the same time, since the intervention of the central bankers and the revelation of US inflation in February (at 7.9%), we observe that the inflation break-even point is clearly rising again. This very imperfect measure of inflation expectations nevertheless shows a change in psychology. Investors suggest that the risk of inflation will be longer and deeper than expected and that this is why central bankers are ready to put considerable resources to deal with it. The recent rise in the nominal rate is only a factor linked to inflation reversing the momentum seen just after Ukraine’s aggression. In the Eurozone, too, the risk of inflation has increased rapidly in recent days.

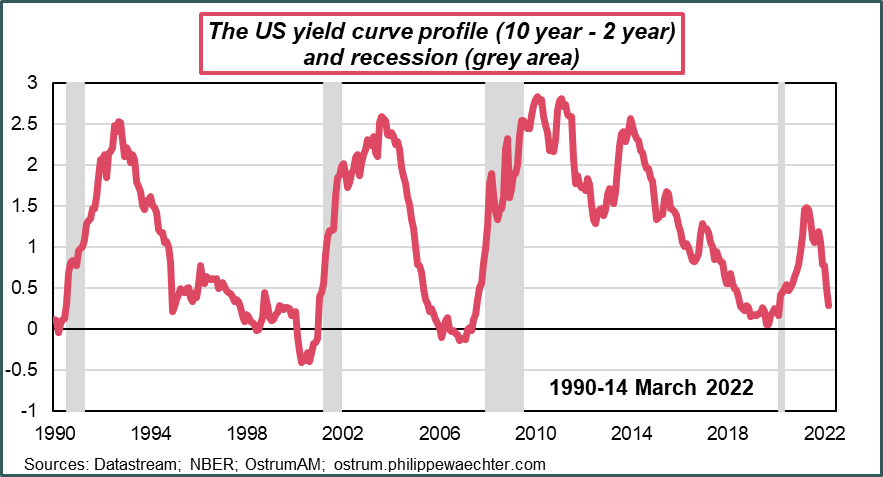

At the same time, the pace of the US interest rate curve does not suggest strong growth expectations. If this were the case, the real rate would rise and the yield curve would experience a slope that would become increasingly positive. Investors do not believe in this scenario and believe that the tightening of monetary policy needed to weigh on inflation will eventually carry growth with it. The graph shows, since 1990, the slope of the US yield curve (10 years minus 2 years) and the periods of recession measured by the NBER.

The current dynamic is interesting. For 30 years inflation has been reduced in developed countries. Since 1985, it has averaged 2.2%. Currently, as the graph shows, the average inflation of the four major countries is above 5%.

This is the unknown for investors who have never experienced such a situation and who have learned that inflation is the element to be avoided at all costs. They prefer a recession to inflation. However, the recession always provokes a dynamic of least expansion.

At a time when the world economy is changing, adjusting to a less cooperative and less coordinated model, is it desirable to do everything possible to curb all forms of adjustment, including inflation?