Oil prices are soaring out of control to slightly above $75/bbl, while the greenback is gaining ground again, and now stands at under 1.2 to the euro with its effective exchange rate rising swiftly and triggering uncertainty on the markets, particularly emergings.

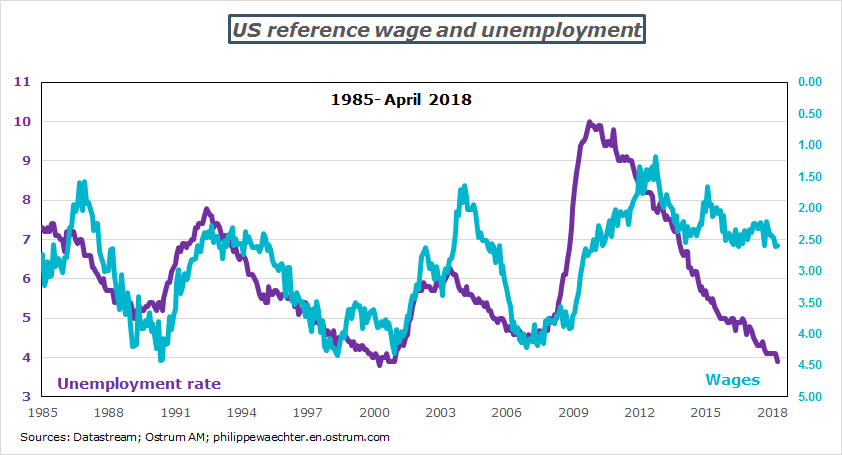

Meanwhile, wages are still not rising in the US, despite unemployment falling below the 4% mark for the first time since December 2000: at the time, the reference wage was up 3.8% vs. an increase of merely 2.6% in April 2018.

Oil above $70/bbl

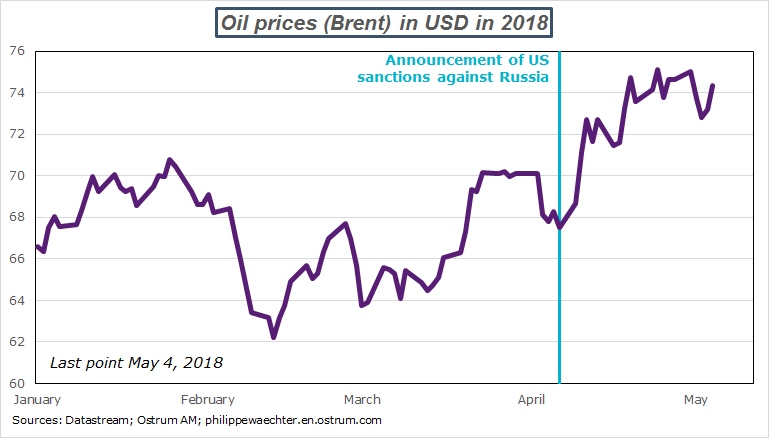

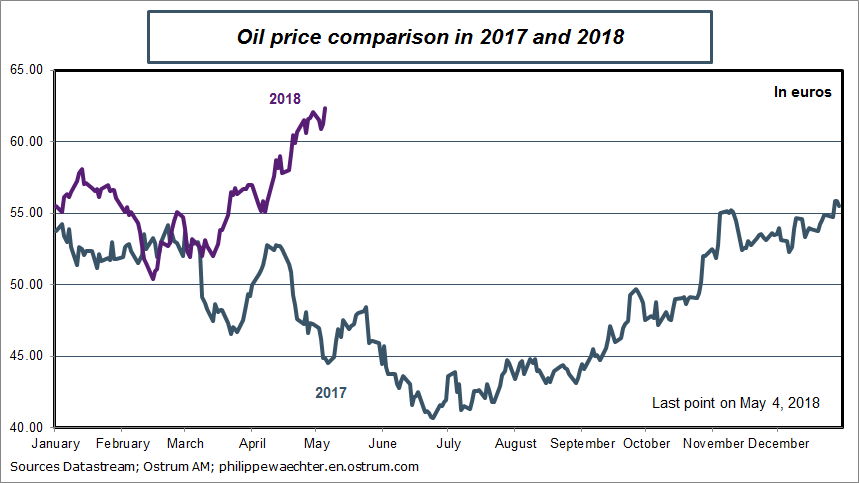

Oil price trends have shifted since the start of April, with figures set on a range of $70-75, compared with a previous figure of around $67 on average, i.e. higher than figures seen since late 2014. This reflected the impact of demand driven by world growth.

The chart below shows that trend altered after April 6, when the White House implemented sanctions against Russia, with subsequent threats on Iran merely serving to amplify this trend.

Sanctions dent one of the world’s largest oil producers, a group that includes Saudi Arabia and the US. Russia would have to keep on investing to sustain production at current levels, but this often requires using foreign technologies and who would take the risk of violating sanctions by financing the Russians and incurring the wrath of the US? So this obviously leads to uncertainty on Russia’s future production.

Meanwhile, the question mark over the situation between the US and Iran on the nuclear agreement also keep the pressure on, but we do not have a clear view of what the outcome of the situation is likely to be.

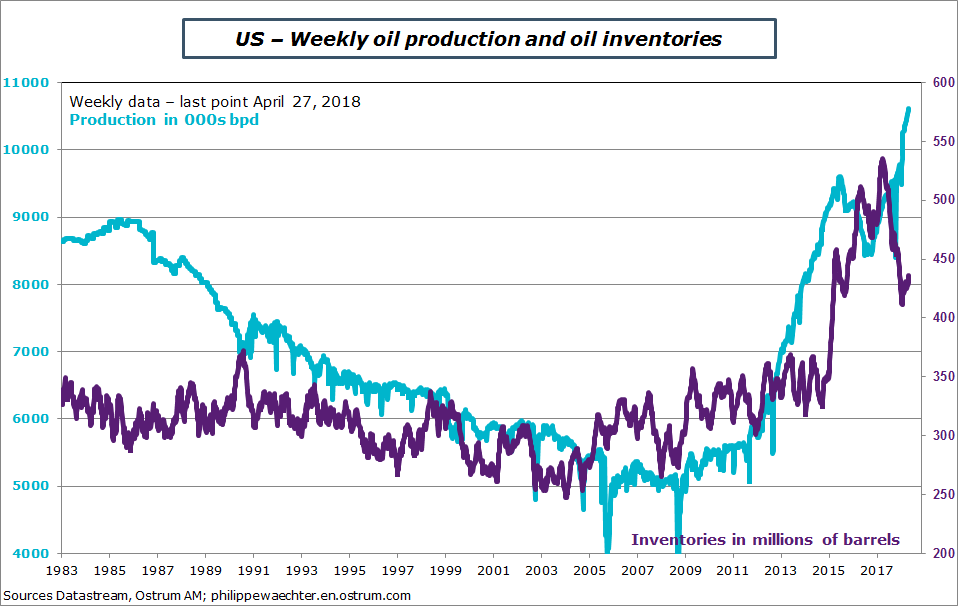

All else being equal, continued US sanctions against Russia and potential measures against Iran tend to push up oil prices, which works to the benefit of US producers. Production continues to grow fast on the other side of the pond, while stocks have now stabilized. The US is the big winner in the current situation, as production has never been so high.

If we compare average oil prices in April 2018 with the same period last year, we see a 16% surge in euro terms and a 33% jump in dollars, and if we apply average April prices to May and June, there is a clear acceleration in both euro and dollar terms.

So the contribution from energy for the euro area would increase from the current 0.25% to almost 0.4% in June before subsequently falling as oil prices firmed up in the second half of 2017 as shown in the chart below.

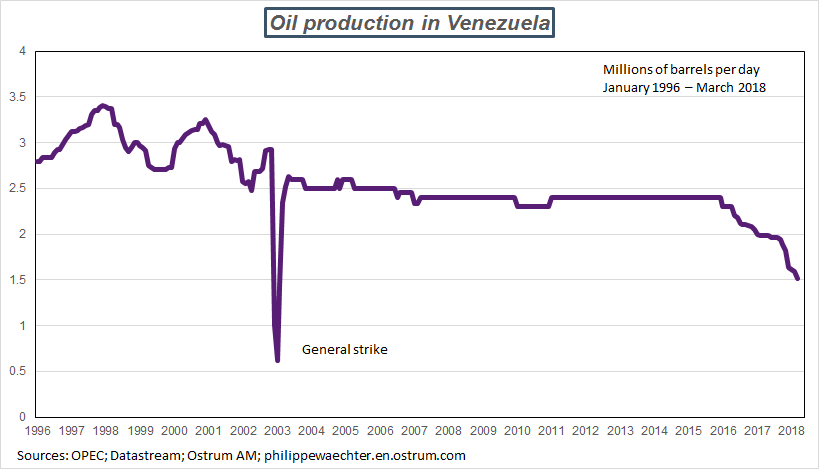

Oil prices could rise again depending on how international tensions and sanctions play out with Iran and even Venezuela following the presidential elections on May 20.

I am expecting prices to remain in the current range over for the months ahead, and Saudi Arabia could potentially raise production to stop prices soaring and hampering world growth. It will be important to keep a close eye on political developments, while at the same time demand momentum is set to be softer as world growth is no longer accelerating.

This means that I do not expect inflation to take a dramatic surge, so no knock-on effect for the rest of the economy. The central banks are therefore set to let the situation continue as it is without intervening.

* * *

The dollar is poised to continue rising

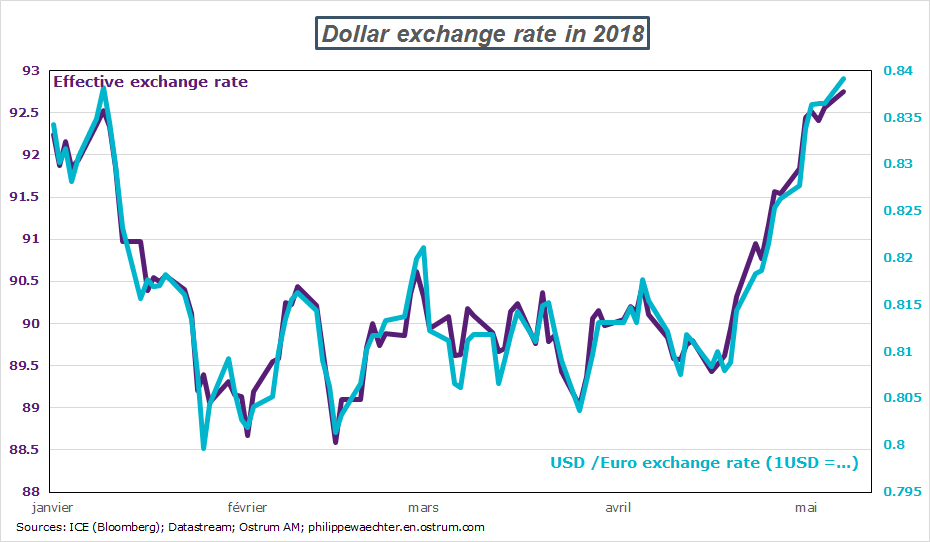

The greenback moved under the 1.2 mark against the euro and the dollar’s effective exchange rate has been on a clear uptrend over recent days. The chart below shows the trends for the two dollar exchange metrics since the start of this year, with the exchange rate against the euro presented as 1 dollar = X euro and not the usual presentation of 1 euro = Y dollar, merely to show that the two metrics have exactly the same pace over the recent period.

The reason behind this is that the dollar has been gaining ground fast since mid-April and has been firming up against all currencies, which also leads to a swift depreciation for emerging currencies.

The policy mix is much too accommodating in view of the very low unemployment rate (the Fed is accommodating and fiscal policy is poised to provide economic stimulus). The Fed needs to be more restrictive.

This change in attitude from the bank is particularly striking as it admitted that it expected slightly higher inflation, as noted in the minutes of the latest meeting, so it will have to be more proactive to avoid the situation spiraling out of control.

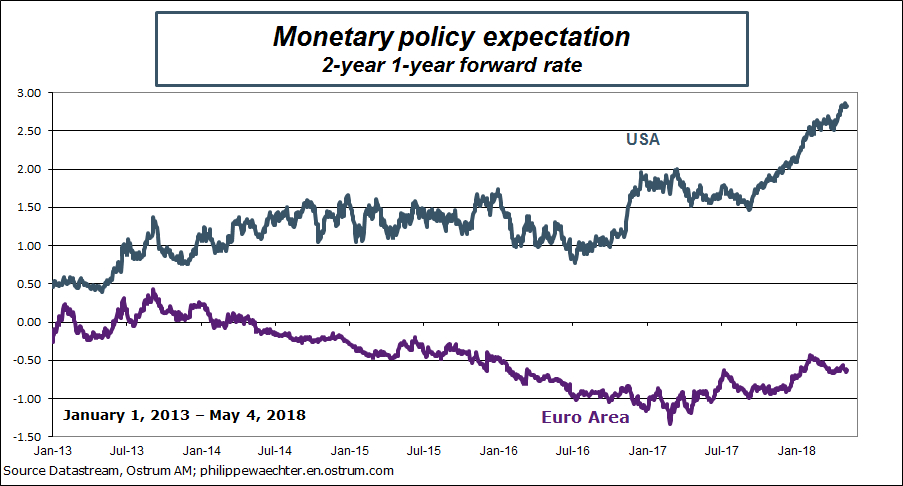

We can compare expectations on the US monetary authorities’ attitude to projections for the ECB in order to achieve a better view of this change.

Monetary policy expectations for the euro area are low and Mario Draghi and the members of the ECB have done their utmost to reduce them for the months ahead.

However, monetary policy expectations in the US are very high and strengthen the appeal of the dollar in arbitrage strategies. We also note that the gap between the US and the euro area has never been so wide since the single currency zone was created.

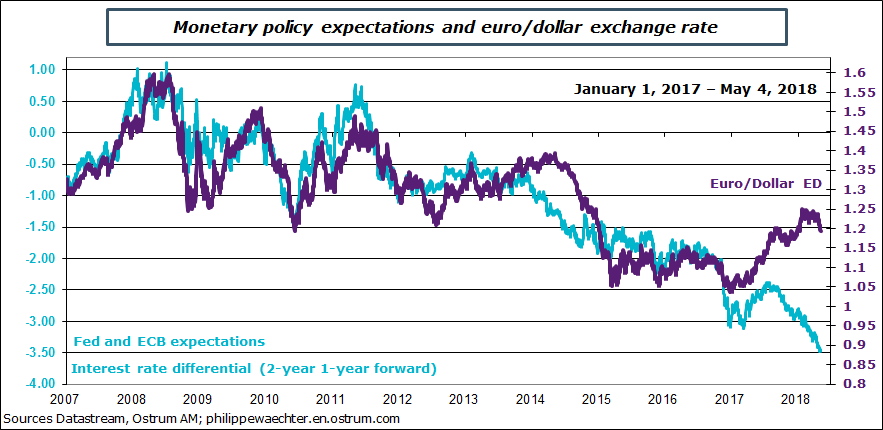

This expectation metric is particularly useful, especially when we look at the differential, which has often been a good prediction of the exchange rate since 2007, apart from since mid-2017 when we see a real divergence.

Monetary policy is set to tighten at a faster pace than expected as the policy mix needs to be rebalanced, so this differential is set to remain substantial over the months ahead as the ECB will still maintain its moderate strategy. The dollar is poised to be stronger against the euro in the weeks ahead and we should expect a move towards 1.10-1.15.

In this respect, we should remember that deficits have a limited impact on the dollar – this is the upside of being “the” international currency, allowing the country to have an external deficit and a currency that holds up well.

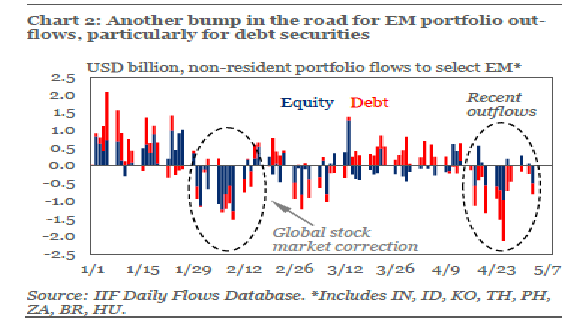

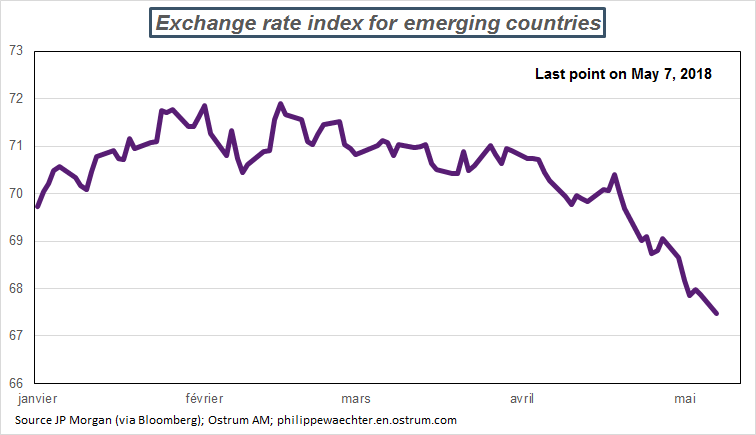

The key question will be on emerging markets: beyond some specifics like Argentina, Brazil and Turkey, the currency’s decline really hampers emerging countries’ financing as on the one hand, the appeal of the US leads to capital repatriation (see helpful chart below) and hence capital outflows from emerging markets, and on the other, this situation creates real difficulties for these countries in finding new financing until such times as the markets think that the greenback needs to stabilize (why invest in a country where the currency is depreciating?).

While the euro area is poised to benefit from the dollar’s gains, the same cannot be said for emerging markets, which are set to face fresh difficulties and will have to tighten their monetary policy sooner than expected.

* * *

Unemployment continues to decline, but wages are still not picking up the pace in the US.

Unemployment fell below the 4% mark for the first time since December 2000, but this did not lead to wage pressure, which remains restricted to 2.6% yoy, as shown by the chart below.

We can see that wages do not display the same cyclical trends as unemployment, and this is a source of concern, triggering doubts among economists on the existence of a Phillips curve (inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, sometimes proxied by wage inflation)

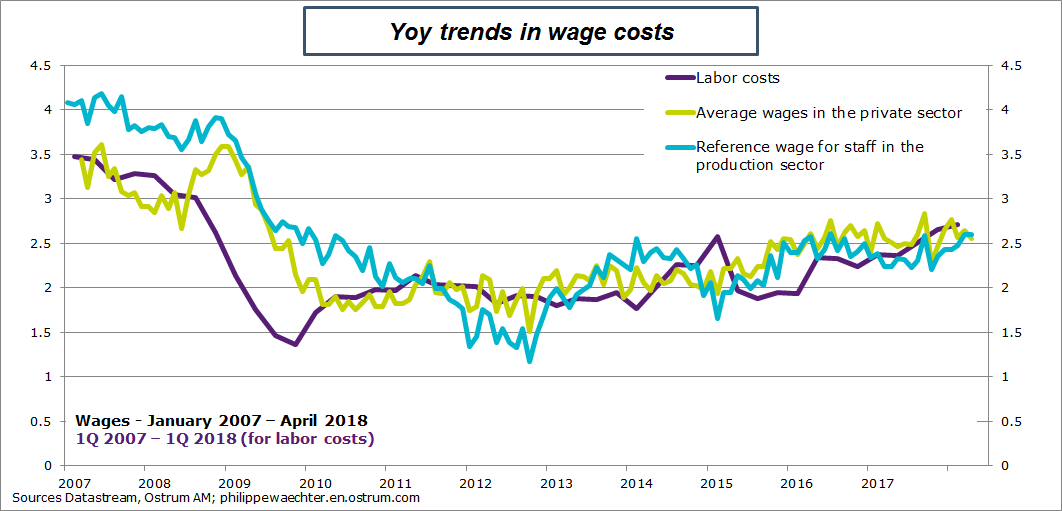

We can change the wage reference by using the employment cost index or unit labor costs but this makes no difference. Employment costs are up 2.7% yoy and ULC gained 1.1% over the same period, so there is no convincing evidence of a rise in wages.

And so the question still remains – how do we explain the lack of wage pressure? Unemployment is low, and other metrics that have recently been used to explain the lack of wage pressure (employment for the 25-55 age group, involuntary part-time work) have improved considerably without leading to significant wage hikes. So the question still remains unanswered.

This could mean that we have to reach an even lower unemployment rate before wages really begin to increase. If this is the case in the US and the UK, then it certainly also applies in the euro area, so if the ECB uses its inflation projections to hike rates, then we are unlikely to see this move any time soon. In a recent article, I calculated that unemployment would have to reach 6.4% for a first rate hike in the euro area in late fall 2019.

____________________________________________________________

* Published in French on May 7, 2018