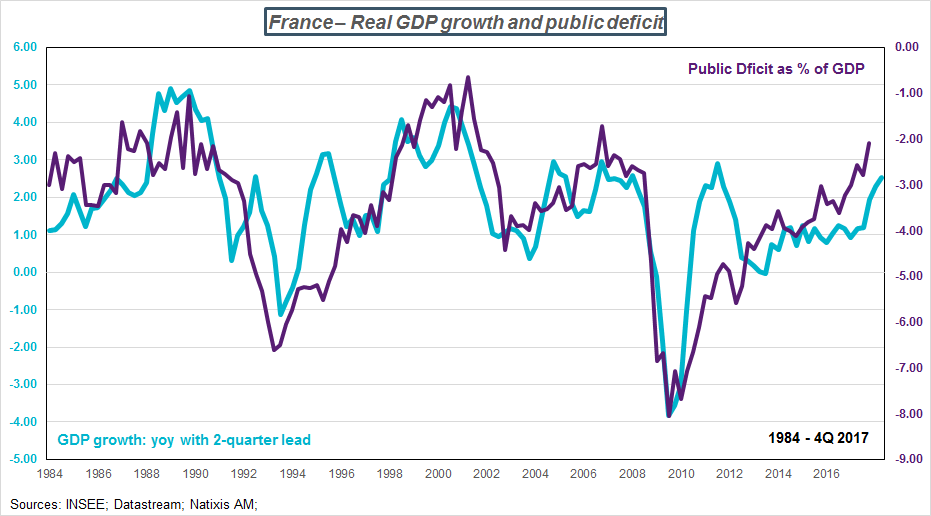

Is the French economy becoming virtuous? With the public deficit falling below the 3% mark, it is tempting to think so… 2.6% for the full year 2017 and 2.1% for the last quarter of the year, so it is really very tempting.

But yet if we look at the figures and the consistency of public accounts with the acceleration in growth in 2017, our bubble bursts as the public deficit profile perfectly follows the trend in growth, which virtually doubled between 2016 and 2017, surging from 1.1% to 2%, so public finances naturally improved. We can see on the chart the strong consistency between the public deficit profile and the pace of real growth with a two-quarter lead. The deficit improves alongside economic growth but it is still difficult to stay on course when growth slows.

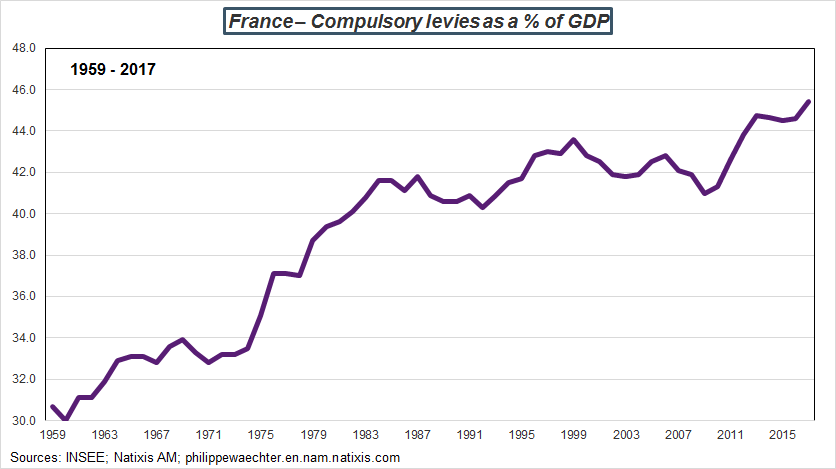

Economic policy measures only had a very limited impact. Spending rose 2.5% and spending excluding interest on debt increased 2.7%. These figures compare with nominal GDP growth of on average 2.8% in 2017. Efforts to cut back spending were very limited as spending edged down from 56.6% of GDP in 2016 to 56.4% in 2017. Meanwhile, revenues benefited from the economic improvement, rising 4% with compulsory levies also increasing, up from 44.6% of GDP in 2016 to 45.4% in 2017, a high in absolute terms since records began in 1959.

The question for 2018 will be the target for public deficit reduction at a time when growth is not accelerating. If we take on board French statistics body INSEE’s forecasts for 0.4% in the first two quarters of the year, growth in France will remain close to 2%. This is when we will observe the real effects of economic policy and the government’s determination to reduce imbalances, so 2018 is set to be an interesting year in this respect. Reduction in the public deficit will no longer be merely a direct and straightforward effect of the pick-up in growth.

The improvement in public finances must be a long-term initiative and requires more far-reaching budget decisions. In light of the Public Finance Planning Act in January, we may not necessarily witness a public finance revolution (see my recent column here). With growth systematically above potential growth, public finance balance would only be reached in 2022 according to the act. The government will have to be more convincing if it is to be deemed to be virtuous and make further efforts on spending.

The publication of detailed growth figures for the fourth quarter helps fine-tune this economic forecast. We note that growth carry-over effects for 2018 at end-2017 stood at 0.9% i.e. if economic activity does not increase across each of the four quarters of 2018, average growth will come out at 0.9%. With growth of 0.42% for each quarter in 2018, average growth across the year will come to 2%. At the end of 2016, growth carry-over for 2017 was only 0.4%.

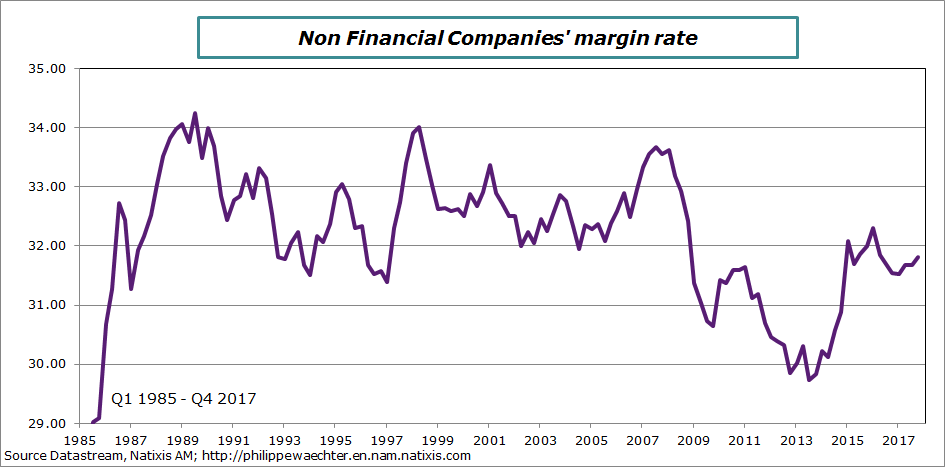

We also note that despite the improvement in non-financial corporate margins to 31.8% in the last quarter of 2017, figures have still not returned to the pre-2008 crisis range (margins fluctuated between 31.5% and 33.5% from 1986 to 2007, with some peaks at 34%). The current catch-up amounts to the lowest point in the previous range, and this is a source of concern as the cycle is already robust yet balance has not yet been recovered.

We can see on the chart that the effects of the financial crisis’ macroeconomic shock were borne by non-financial companies and that since then, they have seen a phase of slow adjustment, despite the French CICE tax credit system and the responsibility pact. We can see here that these two measures were merely aimed at correcting the impact of the 2008 shock.

Companies are often criticized for deriving the benefits of the CICE tax credit and the responsibility pact without investing or recruiting accordingly. But we can see on the chart that they have not yet recovered their pre-crisis balance on average.

I noted here that France displays a very specific feature in that staff wages increased during the crisis phase, unlike other developed countries.

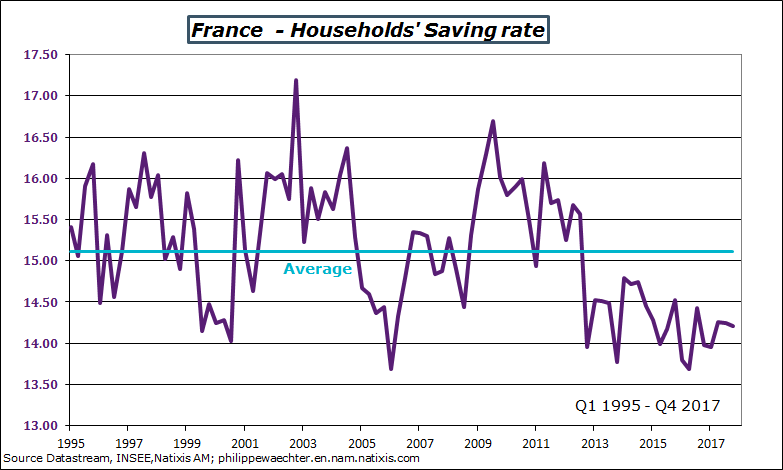

The other point is that household savings remain low, and well below the average seen since 1995: households have reduced savings since 2013 in order to spend more. However, this is entirely in keeping with the ECB’s monetary policy of keeping rates very low in the long term and across all maturities to encourage greater spending. This worked well, and perhaps even too well as household borrowing increased too as income momentum is not sufficiently robust to meet households’ requirements. This balance is not entirely reassuring.

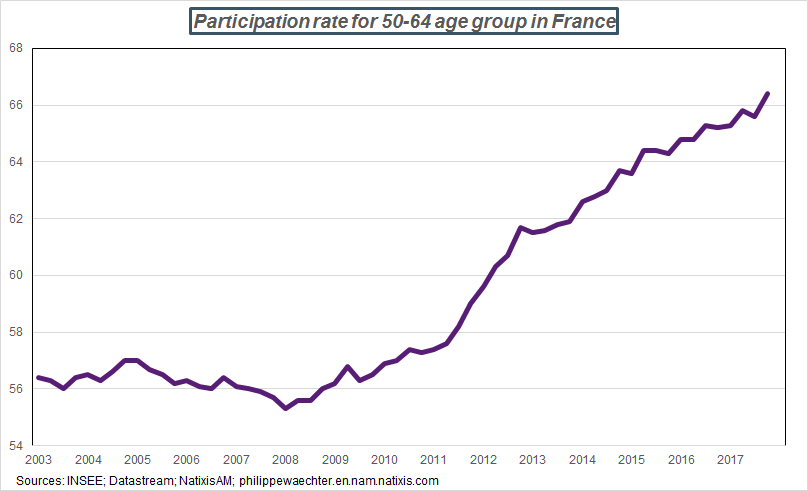

In a recent article, Benoit Mojon and Xavier Ragot explained that a new factor in the labor market is the swift rise in employment for the over-55 age group.

Out of the 7 million jobs created in the euro area since 2013, they note that 6 million have been for workers over the age of 50. In OECD countries, employment among the 55-64 age group rose from 33% to 55% over the past twenty years. In France figures rose by around ten points in ten years, while in Germany, the figure surged from 40% in 2003 to 72% in 2016.

Why look at these figures in detail? According to the two authors, this recent rise in employment rate for the over-55 age group is hampering wage momentum, restricting salary increases despite the acceleration in job creation. Higher labor market participation for the over-55 age group significantly dents wage inflation.

This can be a factor behind the lack of wage pressure at a time when the economy is creating several jobs.

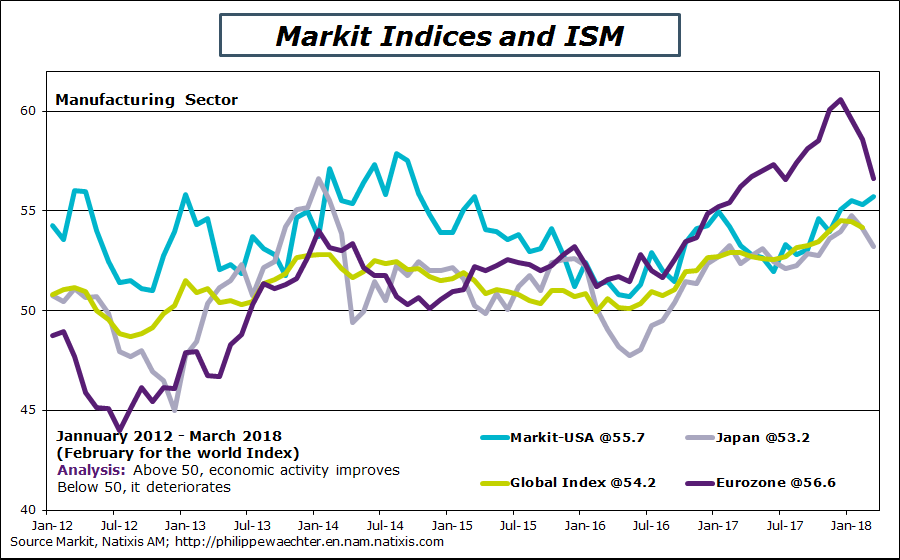

From an economic standpoint, we note that short-term momentum in the euro area and Japan is stagnating. Markit indices along with the ZEW index in Germany and business climate figures in France suggest that business is no longer accelerating from one month to the next, although it continues to rise sharply. This indicates that the recovery is running out of steam in the absence of fresh impetus.

Meanwhile, the Markit index for the US is improving, reflecting the expected effects of fiscal policy.

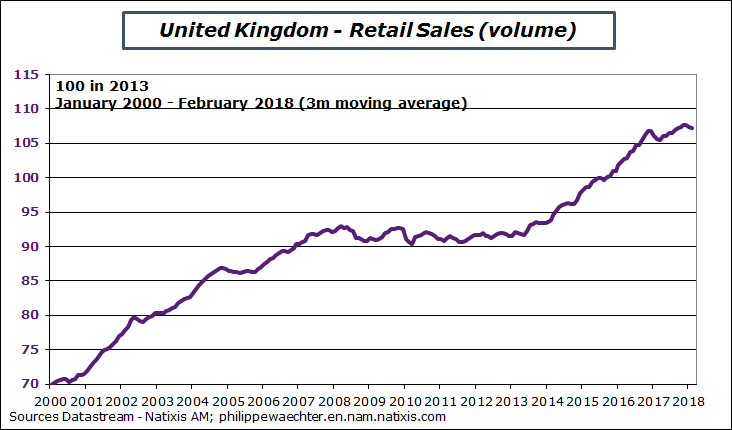

We also note that household spending in the UK is no longer increasing. We can see on the chart that retail sales have been slowing over recent months, while real wages are not increasing.

Another point worth noting is that inflation is slowing in the UK, coming out at 2.7% in February after a peak above 3% (at 3.1%) in November, while core inflation is also decelerating to 2.4%.

If this trend is confirmed, it would be reasonable for the Bank of England to sit tight on monetary policy. At last Thursday’s meeting, it kept its bank rate at 0.5% while indicating that monetary strategy still had a tightening slant due to excessive demand. The BoE cannot alter this stance as inflation is already well beyond its target, and the bank must maintain its credibility. However, I believe that the best policy would be to do nothing until Brexit negotiations provide more clarity.

Looking to the US, the White House’s stance on duties on 60 billion Chinese products and China’s reaction to this make for an unsteady situation. For the moment, China has been fairly accommodating to avoid creating excessive tension, suggesting a change in the rules for foreign financial groups’ holdings in Chinese financial companies, with the possibility of a majority stake. However, the Chinese authorities remain very attentive to US threats and are ready to retaliate if necessary.

This situation is still a threat.

As regards border tariffs on steel and aluminum, it is useful to bear in mind this comment by Adam Posen, President of the Peterson Institute “For every one US worker in metals production there are more than 40 workers in metals-using industries. Taxing the latter to privilege the former makes no sense” (see here).

In Italy, the election success from the Lega and the Five Star movement became official on Saturday as they appointed speakers for both the Senate and Parliament. Between March 30 and April 6, the Italian president must now select a prime minister who can form a government. In light of the tie-up between the Lega and the Five Star Movement, it now looks likely that one candidate could represent both parties and form a broadly anti-European government, using a challenge to reforms on the labor market and pensions as its political platform. If this is the case, the situation in Europe is about to get a lot more shaky and this is challenging.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog