The French government is currently scaling down its growth forecast for 2018. In the initial budget the expected growth rate was 1.7% but was upgraded at 2% in April before being scaled down to 1.7%. Bruno Le Maire the French minister of the Economy and Finance also announced yesterday that the public deficit was expected to be wider in 2018 and 2019. He crosses fingers to maintain it below 3% of the GDP in 2019. For 2018, the deficit is now forecast at 2.6% vs 2.3% expected in April.

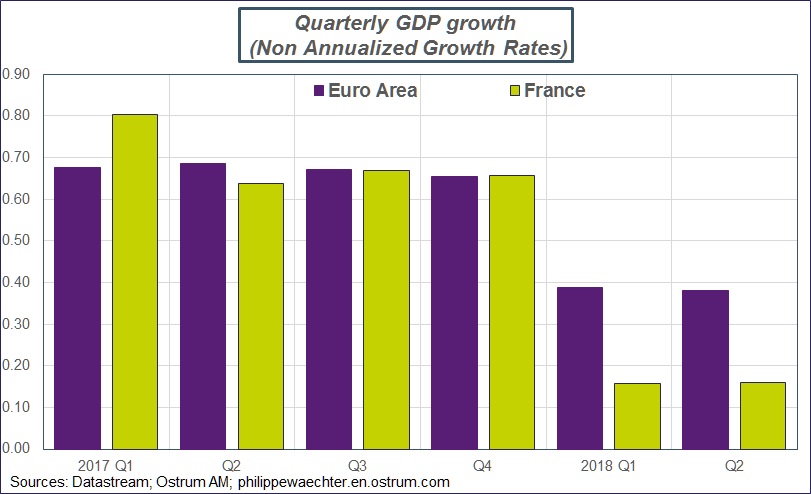

The French growth story this year is interesting. During the first two quarters the growth number was only at 0.16% on average compared to 0.69% on average for 2017 (all the figures are non annualized). This is a division by more than 4. It’s a kind of sudden stop.

The French government has a very general explanation for that. There was a negative shock due to a higher oil price. This explanation is clearly not sufficient as every European country has suffered from a higher oil price.

The first graph compares France to the Euro Area. The two areas usually follow trajectories that are consistent one with each other. This is clearly what was seen in 2017 (and before) but it’s no longer the case in 2018. The European growth has been divided by a factor that is less than 2 (from 0.67% on average in 2017 to 0.39% for the first two quarters of 2018). For France it’s more than a factor 4. Clearly the French economy has suffered more than the Euro Area and the global explanation is not satisfying.

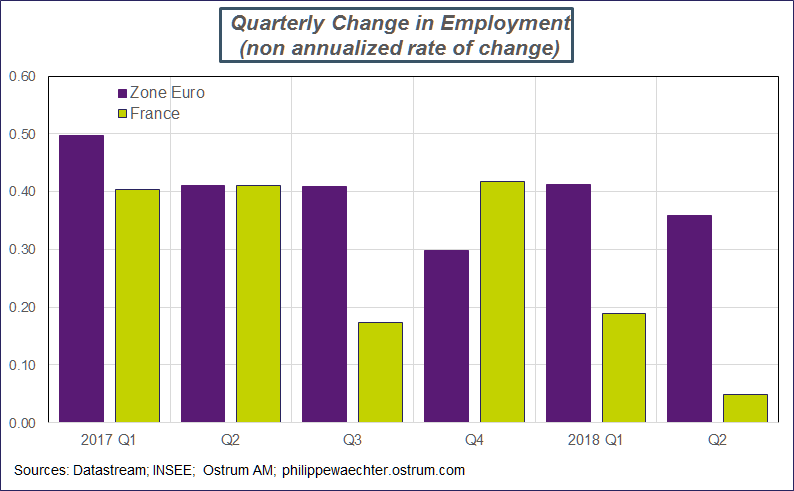

There is another interesting graph which compares employment in France and in the Euro Area (we have had today an update of the two series for the second quarter).

French employment growth has dropped dramatically during the first two quarters of 2018 and the second quarter is weaker than the first. For the Euro Area the momentum is still very strong.

It shows that French companies have negative expectations on the foreseeable future. If the slowdown was just temporary in France, companies would have continue to hire people as a high trend in economic activity was still expected for the future. The rapid drop in employment suggests a negative perception of the future and a weaker demand.

These profiles are interesting as the French government new growth forecast suggests a strong turnaround in the last two quarters. To converge to the 1.7% target a 0.6% growth would be necessary during the two remaining quarters of 2018. If we take the Banque de France forecast for the third quarter (at 0.4%) a growth rate higher than 0.8% would be necessary. During the last ten years, such a growth rate has been attained twice, in the first quarter of 2011 and the first quarter of 2017. It’s quite hazardous.

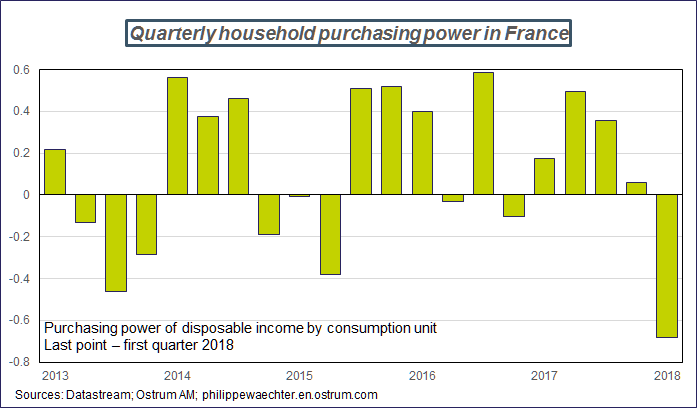

The main explanation for the French low trajectory has to do with its fiscal policy that has led to an important drop in the real disposable income. This fiscal impact will be reversed and probably more than reversed during the last quarter of this year. The government expects a symmetric behavior. The negative purchasing power in the first quarter for fiscal reasons and in the second for higher inflation will be reversed during the last three months of this year. It’s voodoo economics.

My guess is that GDP growth will be close but above 1.5%. The larger purchasing power will be balanced by a lower momentum on the labor market (no reason to expect a reversal on jobs creation in the third quarter). Moreover, in January 2019, the way income tax is paid will change. This tax is paid by less that one taxpayer on two (42% in 2016) but it may create uncertainty and people will want to have a kind of saving to avoid risks.

The last but interesting question on France is related to the potential growth. OECD, the IMF and the French government calculate a potential growth that is close to 1.3%. This means that the observed French growth number will fluctuate around this trend. So after a business cycle peak at the end of 2017, the convergence to the potential growth is not a surprise.

Philippe Waechter's blog My french blog